HOW DID THIS FILM COME ABOUT?

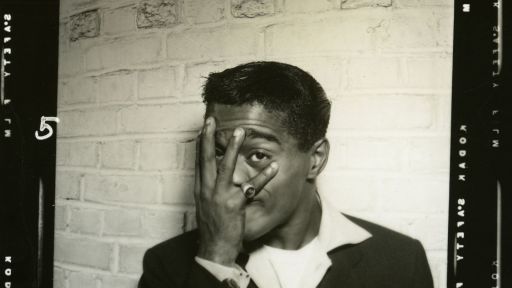

MICHAEL KANTOR (MK): Everyone knows the name Sammy Davis, Jr., and many fondly remember his beautiful singing and fancy footwork, but what does a 21st-century audience know about the man? Do people know that he started his career in blackface? That before the civil rights era, he risked his career by imitating white celebrities in his nightclub act? That he was the first African American to be invited by the President to spend a night in the Lincoln Bedroom at the White House?

For years, writer Laurence Maslon and I had discussed the idea of a film on the life of Sammy Davis, Jr., that would not only showcase his astonishing talents, but also uncover the man behind all the glitz and glamour. Thanks to a major grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities, we were able to create this film.

The project began in earnest in early 2014, so it has taken about three-and-a-half years to complete. I always joke that if one can gestate a child in nine months, you ought to be able to make a documentary in that time, but it never works out that way!

LAURENCE MASLON (LM): I loved Sammy as a kid when I saw him cutting up with corny jokes on Laugh-In. And then I came across a cast album of Golden Boy from 1964, where he played a black prizefighter in love with a white woman during the height of the civil rights era. How could the same performer carry both ends of the spectrum like that? He fascinated me and the more I looked into Sammy’s life and career, the more sides to him there were.

In 1968, Mad magazine did a spoof on how people reduce whole races and cultures to ethnic stereotypes. They had one about blacks—“negroes” at the time—and it was: “One Negro: A Token; Two Negroes: A Boxing Match; Three Negroes: An Emerging African Nation; Four Negroes: Sammy Davis, Jr.” And I thought—that was the whole deal. Sammy was four people and more simultaneously. What a gift and what a struggle. That inspired my approach to the film.

Sammy’s story is even more pertinent today than it was when we started three years ago. Self-identification and self-representation are major cultural issues in the black community—and beyond. Sammy spent his whole life asking questions about his identity (hence the title, “I’ve Gotta Be Me”) that a new generation is putting into public discourse on a daily basis.

SAM POLLARD (SP): Having recently edited a film on Frank Sinatra, I was initially asked to edit this film and ultimately became the director. Growing up with Sammy, it was an honor to tell the story of one of the icons of show business.

WHY THIS FILM?

LM: The world needs to know what Sammy went through. He opened the door for so much of popular culture—not just representation of black entertainers, but the embrace of multi-faceted performers, the role of entertainers in politics, and public vs. private personas. He lived through everything we’re discussing culturally right now.

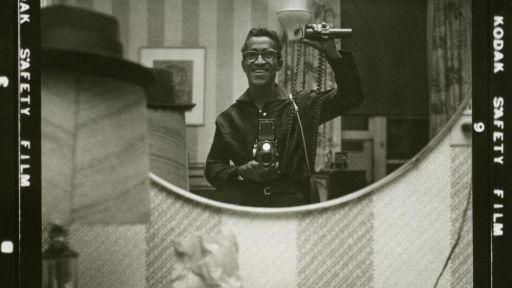

MK: American Masters is dedicated to telling stories that help us understand our culture. Sammy Davis, Jr. was a pioneering black performer and a highly skilled amateur photographer. We used his images throughout the film to explore the evolution of the entertainment industry through his eyes, which provided an incredible lens.

SP: I find my inspiration from many sources as a filmmaker. I am truly indebted to the trailblazing documentary filmmakers DA Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers. I am also inspired by John Ford, Howard Hawks and their complex narrative storytelling, which I always aspire to, even in the documentary form. And finally to St. Clair Bourne, the documentary director who informed me about the importance of telling the African-American story as a filmmaker of color. Sammy Davis, Jr.’s life story is truly one of those important stories that I felt had to be told via film. I am proud to be part of this project.

MAKING THE FILM

MK: Once we had secured permission and access from the estate of Sammy Davis, Jr., and interviewed his friend and co-writer Burt Boyar, the rest was relatively smooth sailing. Sammy’s career is so multi-faceted that one of the challenges was simply to make a documentary that didn’t last eight hours!

SP: I came into the process when at least two-thirds of the interviews had been done. But I was fortunate enough to do interviews with Billy Crystal, Sammy’s former publicist David Steinberg and Professor Todd Boyd. I found Billy and Boyd to be both very incisive about Sammy, his fame and struggles with identity. We interviewed Billy in his bungalow and office, which as he told us was where Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable had their dressing rooms for Gone With the Wind. Before we interviewed him he seemed very quiet, but as soon as he sat in the chair and the camera and sound started rolling he became the Billy we see in the movies: funny and a great storyteller.

Todd Boyd was, on the other hand, energetic and responsive to all my questions about Sammy, and told a great story about seeing Sammy when he was a young man and the impression he left. All the interviewees were engaging and insightful about Sammy’s impact on them, both those who knew him and those who had just watched him in movies or on television.

I think our biggest success was making sure the audience got to see up close and personal Sammy, the man, in his own voice.

LM: The musical of Golden Boy was a major moment in Sammy’s life. He played the lead in an excruciatingly challenging show for three years, on and off. Because the show was so provocative, it wasn’t filmed much in the day, so footage is hard to get. His leading lady, Paula Wayne, came up from retirement in Florida and gave us one of the best interviews I’ve ever witnessed: passionate, frank, outraged—she even sang for us! She’s amazing in the doc.

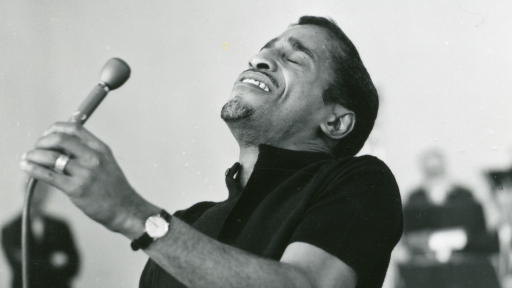

The best way to tell the story was always to cut to Sammy. His presence speaks volumes and his artistry is enthralling. After 20 seconds of watching him, no one could dispute that he was an American Master.

WHAT DO YOU WANT AUDIENCES TO TAKE AWAY FROM THE FILM?

SP: I think the most important aspect of the film, which I feel makes it so special, is Sammy himself, and his commentary throughout the film. He was always probing and questioning his own behavior: how he interacted with people and how they responded to him as both an entertainer and a man of color. It was very important from early on to weave his voice throughout the film.

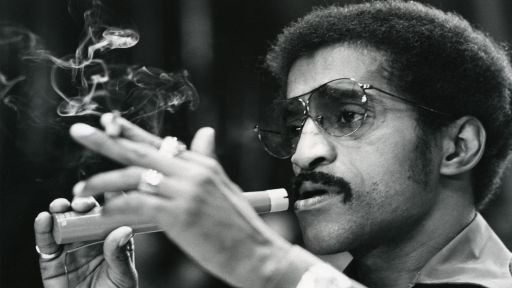

I want audiences to know that Sammy Davis, Jr., was one of the greatest entertainers in the 20th century and to recognize how talented he was as a dancer, singer, impressionist, musician and actor. And that even with all that talent and success, he could never escape the slings and arrows of being a black man in America.

LM: Sammy’s dilemma as a black man in a white world is a truly American story with amazing cultural resonance. But his reach as an entertainer and human being was without precedent and can’t be repeated. He overlapped with most of the key figures in 20th-century American history and culture like a human Venn diagram: Bill Robinson and Michael Jackson; Al Jolson and James Brown; Ethel Waters and Kim Novak; Eddie Cantor and Frank Sinatra; Pigmeat Markham and Sidney Poitier; Clifford Odets and Jerry Lewis; Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis; John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon; Martin Luther King, Jr., and Archie Bunker. All of these intense relationships are covered in the film.

MK: Sammy Davis, Jr. used his talent to fight bigotry, racism and anti-Semitism. He didn’t always win, but he gave it his all. Hopefully audiences will come away from the film marveling at his talent, and wondering why, to paraphrase Sammy’s friend Martin Luther King, Jr., the arc of the moral universe takes so long to bend toward justice.