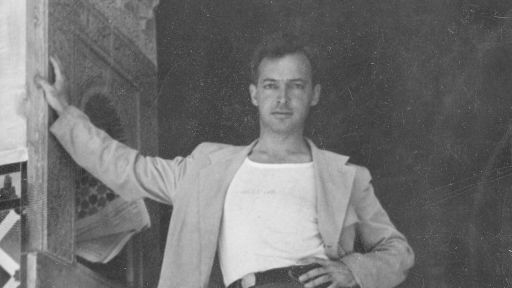

It is only too easy to see Saul Bellow as one of the paladins of a bygone era of American literature, paler and maler than the writers that followed in his wake.

But prior to Bellow and the novelists who emerged alongside him—Bernard Malamud, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth—there was a profound hesitance at the idea of letting anything as precious as American letters fall into the hands of Jewish artists.

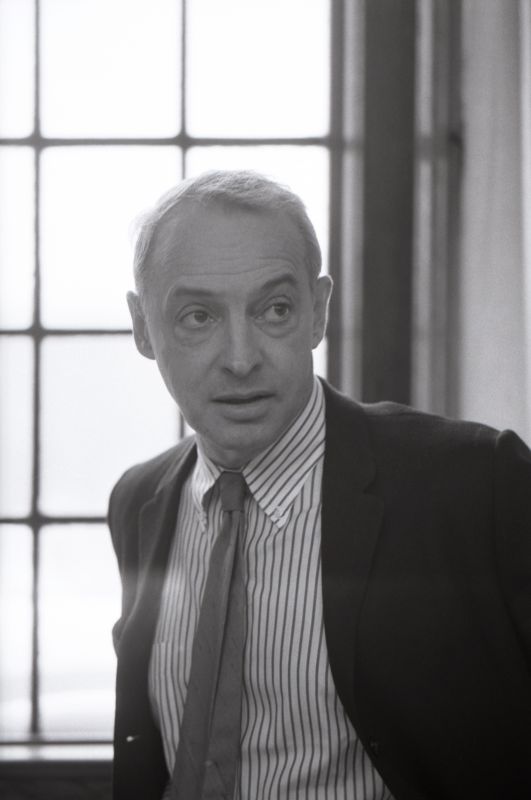

“In my position,” Bellow told the Paris Review in a 1966 interview, “there were social inhibitions too. I had good reason to fear that I would be put down as a foreigner, an interloper. It was made clear to me when I studied literature in the university that as a Jew and the son of Russian Jews, I would probably never have the right feeling for Anglo-Saxon traditions, for English words.”

“I am an American, Chicago-born,” Bellow famously began “The Adventures of Augie March,” his breakthrough 1953 novel, and it is in the missing term— “I am a Jew”—that the novel finds its relentless energy. Alongside Roth, Zadie Smith argues in a perceptive essay, Bellow “utterly dissolved the impossible identity of the Jewish-hyphen-American-hyphen-novelist, until the idea of a Jewish man being a great American novelist seems as natural and obvious to us now as a California redwood rising up out of the soil.”

In “Augie March,” Yiddish and the multilingual demotic of the streets sit pressed up next to elegant French phrases, in much the same way that Augie makes his way sidelong through a city and country equal parts rich and poor, native-born and immigrant, Jew and gentile, law-abiding and criminal, Anglo-Saxon and interloper.

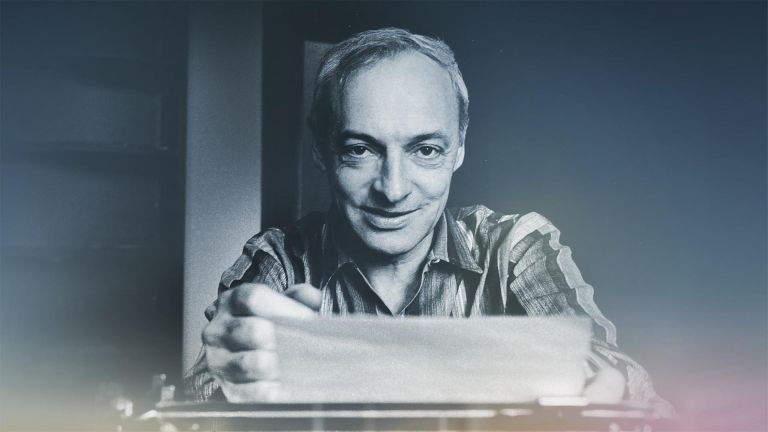

Bellow would later describe his first two novels as overly mannered, written under the sign of Gustave Flaubert. “The restraint of the first two books had driven me mad,” Bellow said. “I hadn’t become a writer to tread the straight and narrow.”

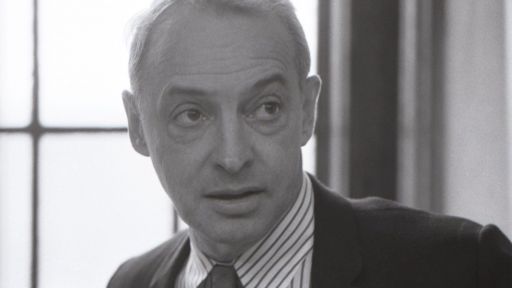

“Augie March“ was about letting a particularly Jewish, particularly American hybrid—wised-up, knowing, approaching the country and its reigning pieties at a slant—emerge. During his Paris Review interview, he asked:

“Why should I force myself to write like an Englishman or a contributor to The New Yorker?”

Bellow had discovered a voice that was restless, comic and yearning, and “Augie March” remains a landmark of postwar American fiction for the sheer life crammed into its pages. It was in the racket and the chaos that Bellow found meaning.

Bellow’s work is filled with the lunks and dreamers and schemers of working-class, white-ethnic urban America, Jews not least among them. And the start of “Augie March” is simultaneously intended as an escape—American, not Jew—and as a reflection of Bellow’s desire that Jewish stories be seen as profoundly American stories. Jewish voices—Bellow’s not least among them— became the touchstone of postwar American fiction, as a generation of writers insisted that the stories of immigrants and lower-middle-class strivers be treated as every bit the equal of Melville or Fitzgerald or Hemingway.

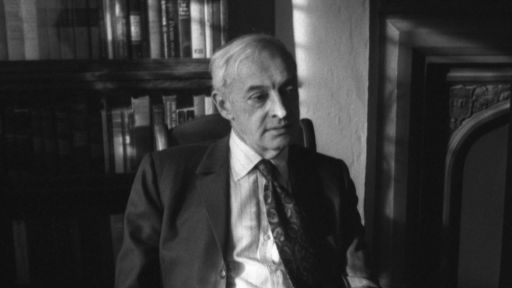

In the wake of “Augie March,” Bellow shifted his interest to a particular kind of highly educated, urban-intellectual crank of the sort that dotted later novels like “Mr. Sammler’s Planet” and “Humboldt’s Gift.” In his 1964 novel “Herzog”—Bellow’s other masterpiece—Moses Herzog wrestles with doubt and loss (his marriage has just fallen apart) by drafting a series of letters: to friends and family members, to his dead mother, to Kant, Nietzsche, and Hegel and to God. Bellow was a cultural conservative at heart, decrying what he saw as the excesses of a society spiraling out of control, but his critique is laced with deep sympathy for the rejects and failures of American life. Herzog is insistent that his own shabby problems and pained yearnings are others’ concern, and in this, we are intended to read a clear message: the American novel is meant to make space for Bellow’s downwardly mobile wise men.

Other novelists of the era took note of the freedoms that Jewish writers like Bellow and Philip Roth extended themselves, and were impressed—and a bit jealous. “In the U.S.A.,” observed Mary McCarthy in “Ideas and the Novel,” “a special license has always been granted to the Jewish novel, which is free to juggle ideas in full public; Bellow, Malamud, Philip Roth still avail themselves of the right, which is never conceded to us goys.”

The Pennsylvania WASP John Updike, went so far as to create a Jewish alter ego for himself, Henry Bech, whose Bellovian excesses and abilities he explored in a series of books. Updike lauded the “soulful, willful warmth” of Bellow’s characters in an essay, underscoring Bellow’s thoroughgoing sympathy for the kinds of characters American literature previously ignored or demeaned. (See Hemingway’s depiction of Robert Cohn in “The Sun Also Rises,” rife with unexamined antisemitism, or Simon Rosedale in Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth”). Bellow and his generation placed Jewish characters unapologetically center circle, and in so doing, they changed what American literature was capable of, and whose stories it chose to tell.

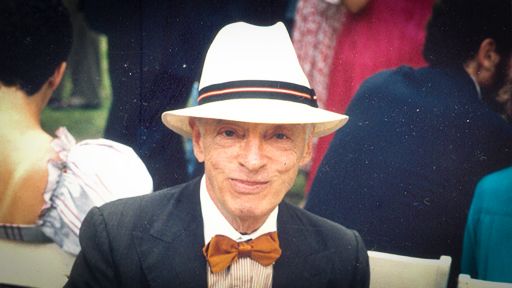

Bellow’s books spoke to people who saw their stories reflected in them. A young reader in Hawaii named Barack Obama would later reflect on reading Bellow and his contemporaries in his memoir “A Promised Land,” and feeling “moved by the stories of men trying to find their place in an America that didn’t welcome them.”

“The spiritual compensation is what I look for,” a character named Dr. Tamkin—himself perhaps a charlatan—observes in Bellow’s short novel, “Seize the Day.”

“Bringing people into the here-and-now. The real universe. That’s the present moment. The past is no good to us. The future is full of anxiety. Only the present is real—the here-and-now. Seize the day.”

Bellow was not particularly interested in religion, not taken with exploring the stifling love of the Jewish family like Roth or retelling parables of Jewish suffering and endurance like Malamud. Instead, he was invested in a messy ideal of particular importance to American Jews: a society with enough space—and enough tolerance— for a wild multiplicity of languages, beliefs and approaches to life. If this ideal feels newly urgent for religious, ethnic and racial minorities in our era of surging antisemitism and white nationalism, well, Saul Bellow would remind us what to say: “I am an American.”