Sandy Rattley’s director statement

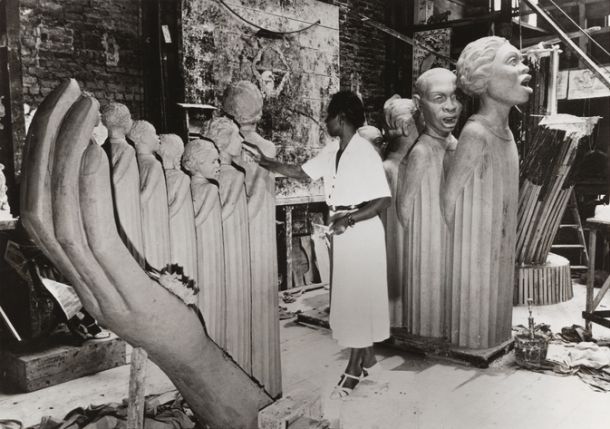

Augusta Savage in her studio working on her 1939 New York World’s Fair monument “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Augusta Savage (1892-1962) is an amazing woman who overcame great odds to accomplish many firsts in her 70 years of life. On the global stage and while at the height of her career, she became the only Black artist, and one of four women, commissioned to create an exhibit for the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, NY. She decided to create a tribute to her friend from Jacksonville, Florida, former NAACP head and poet, James Weldon Johnson, who had composed the lyrics for the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Augusta Savage took over a year to create a 16-foot sculpture depicting a choir of 12 Black children singing, arranged like strings on a harp held up by the hand of God. Her monument to Black culture and the promise of Black youth, also known as “The Harp,” was among the fair’s most visited and photographed exhibits seen by more than five million people. Yet tragically, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” was bulldozed when the Fair closed, as Savage was not able to raise the funds to transport and store it, or have it cast in durable materials.

More than half of the 160 works of art Savage created are missing or have been destroyed, and none of her monumental large-scale works have survived.

Our film is titled Searching for Augusta Savage because we wanted to investigate why evidence of Savage’s accomplishments and her work appear to be erased. We wanted to know how someone so accomplished, so enterprising and so celebrated during her lifetime, could be missing from the annals of American history and the museum landscape.

We found that Augusta Savage was fearless and outspoken.

She protested against an incident she experienced in 1923, when she was accepted, and then rejected from participation in a prestigious art fellowship in Paris because of her race, initiating a letter writing campaign and speaking out in editorials and interviews in mainstream media. She also resisted sexism, even from some of her counterparts in the Harlem Renaissance, such as scholar Alain Locke, who questioned Savage’s academic credentials and why she was the subject of so much media attention.

Also, because of her association with Black identity movements such as the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and other progressive causes, Savage was being investigated by the FBI. But these challenges did not deter her art activism or her art practice, including writing poems and children’s stories. Throughout her life, Savage continued to teach art to children everywhere that she lived – in Florida, Harlem, and Saugerties, NY, where she spent the last two decades of her life.

The fact that so little of Augusta Savage’s work is in the permanent collections of museums and available to the public is an issue that has relevance today, as Black women continue to be the artists with the lowest representation and visibility in the art marketplace. As reported in the 2022 Burns Halperin Report, between 2008 and 2020, just 11% of acquisitions, and 14.9% of exhibitions at U.S. museums were of work by female-identifying artists, and only 2.2% of acquisitions, and 6.3% of exhibitions were by Black American artists. Just 0.5%, that’s less than 1% of acquisitions, were the work of Black American women.

To counter the fact that much of her art is not available today, we collaborated with new technology artists to bring it back to life.

Artists worked to create and animate interpretations of Savage’s most impressive lost work of art, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the 16-foot sculpture she created for the 1939 World’s Fair which is reconstructed in the film. Informed by Savage’s own words and writings, we also recreated major moments in Savage’s early childhood for which no archival or visual documentation exists. We feel that digital reconstruction can be a powerful tool for remembrance, helping us reverse Savage’s historical erasure.

Augusta Savage had tremendous resolve and commitment. Her sense of mission and self-determination are legendary, especially for a young Black woman from the South in the 1920s. She has been called a “waymaker” for confronting racism and overcoming countless obstacles, and for being so dedicated to creating careers in the arts for so many Black artists and aspiring artists. Her experiences countering under-representation in the art world still resonate today. It has been a privilege to tell her story and provide testimony to the life, work and example of Augusta Savage!

More about Augusta Savage

Born in 1892 in Green Cove Springs Florida, she had a strong desire to be an artist and work with clay at a very young age, a pastime that both her parents vehemently opposed. Her father was a Methodist minister who saw the animals she made as sinful graven images. Savage said that her parents “practically whipped the art out of [her].” She persisted. Initially self-taught, she entered a bust of former West Palm Beach Mayor, George Graham Currie, her interpretation of a wild stallion she modeled using a donkey, and a few religious statues in the 1919 West Palm Beach County Fair, exhibiting her work between stalls of farm animals, fruits and vegetables. Savage won a blue ribbon and $25 prize, and her passion and promise were so contagious that the fair’s attendees spontaneously took up a collection to support her dream of becoming an artist and send her to New York.

Before moving to New York City, Augusta Savage spent time in Jacksonville, Florida trying to convince “wealthy Negroes” to have busts made. But that plan did not pan out. In 1921, Savage took a train from Jacksonville to the Big Apple wearing a homemade coat with $4.50 in her purse. After completing a 4-year art course at Cooper Union in three years, she became one of the leading influencers of the Harlem Renaissance, was acclaimed as one of the most talented artists of the time period, and called “Sculptress of the Negro People” because she centered Black life in her work.

Before moving to New York City, Augusta Savage spent time in Jacksonville, Florida trying to convince “wealthy Negroes” to have busts made. But that plan did not pan out. In 1921, Savage took a train from Jacksonville to the Big Apple wearing a homemade coat with $4.50 in her purse. After completing a 4-year art course at Cooper Union in three years, she became one of the leading influencers of the Harlem Renaissance, was acclaimed as one of the most talented artists of the time period, and called “Sculptress of the Negro People” because she centered Black life in her work.

Savage opened the first gallery in the United States dedicated to the work of Black artists; mentored a generation of venerated artists, including Romare Bearden, Gwendolyn Knight, and Jacob Lawrence; and founded several organizations that provided free art education and training to over 2,500 people in Harlem, NY. She was also the first African American elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, later renamed the National Association of Women Artists.

About filmmakers Charlotte Mangin and Sandy Rattley

Charlotte Mangin is a documentary filmmaker with over 20 years of experience in multimedia storytelling, fundraising and nonprofit management. She was the creator, executive producer, director, and writer of Unladylike2020, an animated documentary series about unsung women who changed America at the turn of the 20th century. She spent five years on the production staff of National Geographic Television & Film, reporting from the jungles of the Amazon to the Himalayan Mountains. Mangin produced a dozen documentaries for PBS’s international affairs series Wide Angle, covering issues such as legal reform in China, human rights in Zimbabwe, and race relations in Brazil. Her hour-long Wide Angle program, Class of 2006, about women’s rights in Morocco, won an International Documentary Association Award. Mangin was nominated for 4 Emmy Awards for Pioneers of Thirteen, a 6-hour series commemorating the flagship PBS station’s 50th anniversary.

Sandy Rattley has over 40 years experience leading and launching multimedia projects. Rattley was also executive producer, director and writer for Unladylike2020. She was senior story editor of the Spotify podcast series The Sum of Us, hosted by author Heather McGee. Rattley was also executive producer of seminal documentary projects including the Peabody Award winning series Wade in the Water about African American sacred music, produced by NPR and the Smithsonian Institution, and Making the Music, hosted by Wynton Marsalis, produced for NPR and PBS. Rattley is the former VP for Cultural Programming at NPR where she launched the weekly show, Wait, Wait Don’t Tell Me, as well as NPR’s office of civic engagement. She serves as creative consultant for Black Public Media’s 360 Incubator, a mentorship program for African American media makers. Rattley also founded, launched and produced the Africa Learning Channel, a Pan-African news and information service, streaming via WorldSpace satellite to over 100 million listeners in 51 African countries.

About narrator Jeffreen M. Hayes, Ph.D.

Jeffreen M. Hayes, Ph.D., a public art historian and curator, merges administrative, curatorial and academic practices in her support for artists and community development. As an advocate for racial inclusion, equity and access, Jeffreen invites community participation into the projects she initiates and manages, to ensure art’s relevance beyond the walls of museums and galleries. Her curatorial projects include SILOS (2016-18), Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman (2018-2020), AFRICOBRA: Messages to the People (2018), Process (2019), AFRICOBRA: Nation Time (2019), and most recently, Dreaming of a Future (2023).

Hayes writes about art history, Black art and visual culture, and arts activism. Some of her books include Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman, AfriCOBRA: Messages to the People, and Etched in Collective History. She is a TEDx speaker and has spoken at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Norton Museum of Art; ArtPace; Rollins Museum of Art; and Columbia College among other arts organizations and institutions. She has served as the Executive Director of Threewalls since 2015, providing strategic vision for the artistic direction and impact of the organization to connect segregated communities, people and experiences in Chicago.