Since Slacker premiered at the Dobie Theater, the lifestyle it celebrated is largely gone, along with the locations it helped make famous. In this “Slacker map,” we look at what’s disappeared and what’s endured.

Written by Marc Savlov, this article was originally published by the Austin Chronicle on January 26, 2001. Read the original piece here.

slacker (slak’er), n. One that shirks work or responsibility, especially one that tries to evade military service during wartime. – The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition, 1992

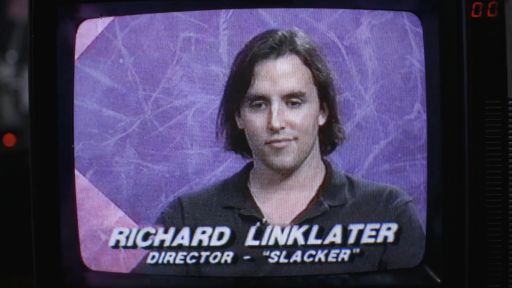

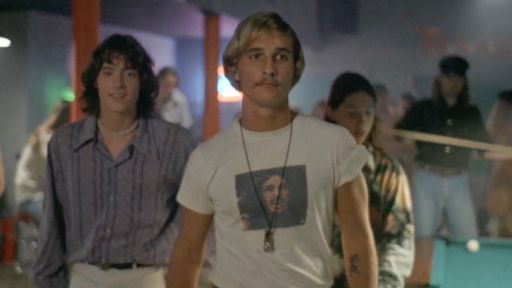

It’s been more than a decade since Slacker premiered at the Dobie Theatre, thrusting that little-used term into the mainstream alongside a picture-perfect chronicle of an Austin era now long since faded. In the time in between, Slacker has morphed from a small film about a (reasonably) small community in a (somewhat) small town to legendary status, right up there with Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape and Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. Like that latter film, Slacker freezes a specific community’s zeitgeist and traps it forever on celluloid; sometimes I think it’s less of a movie, per se, than some funky historical object. Richard Linklater’s film should be required viewing for the hordes of new arrivals that began inundating Austin some four years ago. Of course, the film’s popularity – and the cultural popularity of the “slacker lifestyle” that it engendered – almost certainly sounded the death knell of the very community it was celebrating. That’s the way things work sometimes.

By Jason Stout

In his “making of” book (St. Martin’s Press, 1992), the following passage, Linklater’s own, appears: “I guess it all started for me when I wandered into a Dead Kennedys show in the summer of 1984. …As Jello Biafra took the stage and started belting, ‘MTV – get off the air, now!’ or about how, in relation to the star quarterback having his neck broken, the Coach said, ‘That boy gave 100%,’ I suddenly felt a surge of energy …In a very short time, I went from thinking (as I had been told over and over again) that my generation had nothing to say to thinking that it not only had everything to say but was saying it in a completely new way …Each individual had to find it in their own way, and in the only place society had left for this discovery – the margins. I think that’s where Slacker takes place.”

Oddly enough, that Dead Kennedys show – at Liberty Lunch, with openers BGK, Cause for Alarm, and Austin’s the Offenders – was also my first eye-popping punk rock gig. And when, in 1992, Linklater’s film was suddenly meriting major media attention from CNN, The New York Times, and a hundred other arbiters of cultural taste, my father called me up to discuss an article he’d read on “Austin’s slacker phenomenon,” wondering, no doubt, if I was a part of this vague anti-movement. I told him yeah, I supposed I was, and did my best to explain to him what it all meant, if anything.

Slacker cameraman Clark Walker wrote – also in the Slacker book – that the term had become a handy catch-all word. “In a sense, we were all slackers,” he writes. “Aside from a consuming passion for cinema, what we held most in common was a desire not to work for a living, if work meant doing anything we didn’t love.”

The map above, illustrated by Jason Stout, is intended to serve as a walking tour of locations used in the film. The task was baffling; the film covers so much of the city, often so quickly, that the final product couldn’t help but be incomplete. Instead, we focused on the film’s – and the city’s – most integral locations. Much of what you see in Slacker today is long gone, but like a good friend since passed, the memories of the fundamental locales linger in the minds of those who were present at this magical, formative time. And, of course, depressed, aging slackers such as myself can always pop in the Slackertape, crack a cold Shiner Bock, and return to the old school. Who says you can’t go home anymore? Not Rick Linklater, and certainly not Slacker itself.

1. Bus station at Highland Mall

“Man, I just had the weirdest dream.”

2. Mad Dog and Beans, 24th & Nueces

“Whose body is this?”

Now part of the “revitalized,” vaguely French Quarterian complex that houses Smoothie King and – oh, the irony! – Starbucks, Mad Dog’s, as it was known, remains one of the best examples of burger culture I’ve ever known. Dating back to the mid-Seventies, the small, wooden, caboose-like eatery, with its scruffy picnic tables and general air of hungover camaraderie, served the best milkshakes and gooey, almost erotically excellent hamburgers, playing host to a kaleidoscope of Austin artists, musicians, filmmakers, and Dragworms.

3. Ollie Trout’s (“the Fingerhut”), 2405 Nueces

“Oh, drag. Did anybody get a license plate number or anything?”

Is there no shame in the world? It’s now (or was, until its recent closure) a Johnny Rockets hamburger joint. At the time of Slacker, it was the home of Linklater, the film’s DP Lee Daniel, Clark Walker, and one of the handful of places in town where Janis Joplin supposedly slept.

4. Captain Quackenbush’s Intergalactic Dessert Company and Espresso Café, 2120 Guadalupe

“Who’s ever written the great work about the immense effort required not to create?”

University-front real estate prices being what they are, the former site of Austin’s premier java joint is empty for the time being. Back in the day, though, Quackenbush’s was the nexus of Austin’s Drag-based creative community, a place for students, punks, slackers, and the odd muttering homeless guy to drench their dreams in some of the finest caffeinated Colombian Austin has ever seen. Quacks’ lazy ambience was pure old-school Austin. The open-air front patio fairly begged passersby to stow the trig homework and curl up with Subterraneans or something equally beatastic, and hotshot espressos would keep you jittery enough to nail the coursework later, after the important things got done.

5. Party house, 809 W. MLK

“Can I have his room?”

Those of us who were here during the “slacker era” miss a lot of things about that particular period, but most of all we miss the micro-rents that allowed the habitually broke artist types to keep a decent roof over their heads and still have enough green left over for a keg of Shiner and some of the other green. This former site of the Green Acres Co-op and “massive party house” is now a B&B known as the Inn at Pearl Street. A cool place, yes, but try inviting the Butthole Surfers over for an impromptu session of late-night debauchery. Not bloody likely.

6. Second Street Warehouse

“It’s a Madonna pap smear. I know it’s kinda cloudy, but it’s a Madonna pap smear.”

Three consecutive scenes were filmed on different sides of this downtown warehouse, right across from the now-razed Liberty Lunch, chosen in the same improvisational way that many of the film’s locations were selected. As cameraman Clark Walker remembers, “That morning, without a prior plan, the entire cast and crew piled into one or two cars and drove around the central city, which was deserted, looking for quiet places so we could record sound – no cars and few pedestrians. No permit, no tech scout, we just pulled over when Lee [Daniel] said the light was good and Rick [Linklater] thought he could do the scene there without being bothered.”

7. G/M Steakhouse, 626 N. Lamar

“You should never, never traumatize a woman sexually. I should know. I’m a medical doctor.”

“Stop following me!” growls Chronicle Editor Louis Black in one of Slacker‘s many cameos. Amazingly, the G/M is still there, although rumors of its demise often circulate. In the meantime, though, it still serves some of the best diner breakfasts in town and exists as a reminder of Austin’s smaller, cooler past, surrounded as it is by all sorts of new construction.

8. E. MLK bridge

“The typewriter isn’t the point. The point is it symbolizes the b**** that just f***** him over. It symbolizes the b**** that f***** me over six months ago, and it symbolizes the b**** that’s gonna f*** you over.”

9. Sound Exchange, 2100-A Guadalupe

“You’re just pulling these things from the s*** you read.”

10. Half Price Books, 3110 Guadalupe

“You know me, I’ve been keeping up with my JFK assassination theories.”

11. South Congress Junk Yard

“Are you gonna pay for that?”

12. Les Amis Café, 504 W. 24th

“To hell with the kind of work you have to do to make a living.”

Right next to the also-now-departed Inner Sanctum Records (“Austin’s first independent record store!”) inside Bluebonnet Plaza, Les Amis’ lovely outdoor/indoor sidewalk cafe was a habitual stop for students and slackers alike, a place where nobody cared if you stayed all night — in fact, it was almost expected. Cheap house Merlot and cheaper entrées — black beans and brown rice and cheese, yeah! — went easy on the wallet and provided more existential, late-night conversations than any other place in town. It’s now a Starbucks, which just goes to show that God can be a real smart-ass when he wants to be.

13. Foodland, 1120 S. Lamar (now City Market)

“I’m always glad to see any young person doing something.”

14. Parking lot off I-35

“Well, that’s her menstrual cycle.”

15. Les Amis

“A friend of mine has this weird theory about the Smurfs.”

16. Blue Bayou, 2008 S. Congress (now Trophy’s)

“I’m on the guest list. Steve plus three, or four.”

17. Austin Media Arts, 2120 Guadalupe

“It’s my Pixelvision camera. It’s for a project I’m putting together.”

Some of the most important film screenings and series in Austin’s history took place in this smallish space above Quackenbush’s, a natural choice for coffee-starved cineastes like Linklater, D. Montgomery, and Lee Daniel, who used the venue to unspool the works of Stan Brakhage, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Jean-Luc Godard, as well as a host of other artistic endeavors specifically tailored to the funky art-happening groove of the AMA.

18. Continental Club, 1315 S. Congress

“I’m an anti-artist.”

19. Mount Bonnell, 3800 Mount Bonnell Dr.

Ready! Set! Throw! Slacker‘s famous final scene of Super-8s flying earthbound over the edge of West Austin landmark Mount Bonnell (overlooking gorgeous Lake Austin from a distance of 785 feet) is as indelible a cinematic moment as you could hope for. Formally dedicated as a Texas state park in 1938, this is one Slacker landmark that promises to stick around long enough for the film to finally come out on DVD. No sign of a cliff-top Starbucks just yet, and still plenty of treacherous overhang for the local heshers to go get sloppy beneath.

Special thanks to Clark Walker, Lee Daniel, Robert Pierson, Kathy Crane, and Detour FilmProduction

Funding for Richard Linklater – dream is destiny is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.