Ojibwe myths in the art of Jonathan Thunder

The Ojibwe (Chippewa) have a rich, living culture that includes thousands of legends, stories and songs that range from sacred and ceremonial to pure entertainment.

Jonathan Thunder, who is Red Lake Ojibwe, brings this rich oral tradition to new light in his recent works, including the animated Manifest’o, which is on active display in the Minneapolis Airport tunnel between concourses A and B.

Thunder is like a Native American Salvador Dalí. His work is surreal at times, but informed by history, always making a statement about the world—past, present and future. He makes you think.

Here are two myths featured in Manifest’o:

Aginjibagesi, The Leaf Counter

Thunder has a section on Aginjibagesi (The Leaf Counter), a spirit name for the American Goldfinch.

This colorful bird is seen by many Ojibwe as the spirit keeper of the Ojibwe language. Traveling the tunnel at the airport, we are transported into the woods with the birds counting the falling leaves and keeping watch over the language.

It’s a powerful reminder that we often walk by, through, and over the animals, birds and insects, ignoring the sacred – oblivious to the deeper meaning in all of creation. But the art offers an opportunity to reconsider our ignorance and think about the woods and water, the animals, birds and fish, and our place in creation.

It’s a widely held view in the Ojibwe world that we are not the masters of the web of life, but part of the web, connected to and dependent on everything in creation. This is reflected in the floral patterns common in traditional Ojibwe art forms—reminding us that the plants were placed here first, followed by the animals, birds and fish. Humans arrived last of all. If humans disappeared from planet earth, everything put here before us would get along just fine—perhaps better than ever.

| Watch Jonathan Thunder: Good Mythology, directed by Sergio Rapu |

But if anything put here before us were to disappear, surely we would too. It’s a coded invitation to consider the future vitality of the Ojibwe language and everything the language means, not just to Ojibwe people, but the world. Every language holds a unique way of looking at the world. We can consider, through this art, how the first people of this land viewed the natural world and everything in it.

Mishi-bizhiw, The Great Panther

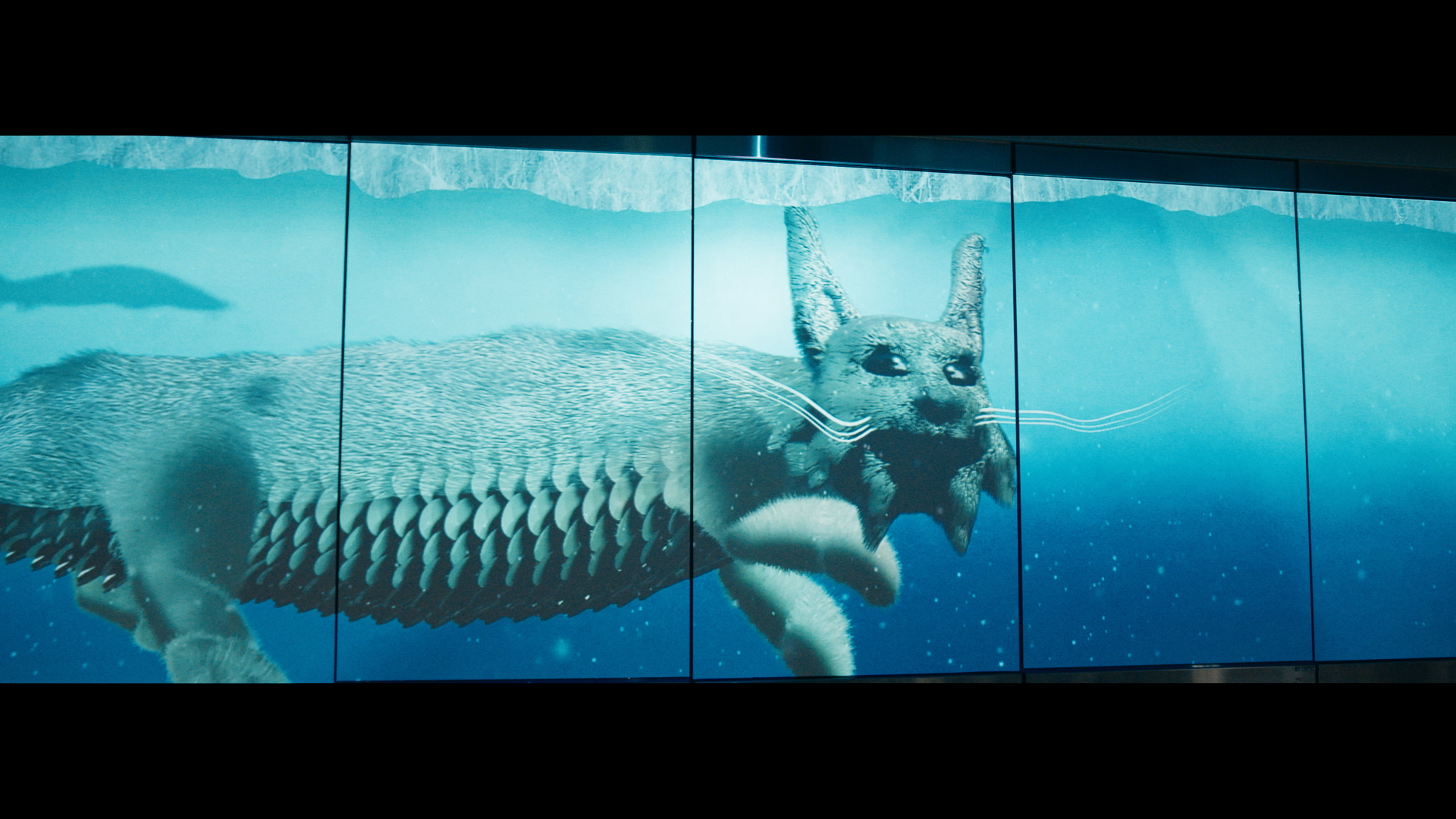

Manifest’o features the story of Mishi-bizhiw (The Great Panther), who is the head of the water spirits.

It sounds strange to some that Ojibwe legend describes the head of the water spirits as a feline, but that’s just the beginning of the mysteries around Mishi-bizhiw. At times, Mishi-bizhiw engaged Wenabozho (a central figure in Ojibwe legend who is half human and half spirit) in epic battles, which gave rise to apocalyptic events.

Yet Mishi-bizhiw is a force for good, mentioned in Ojibwe prayers and ceremonies still today. Thunder has him swimming through the tunnel of the Minneapolis Airport, reminding us of the sacredness of water and the eternal presence of spirits in the water.

Water was put in creation before any growing things or beings. Babies grow in utero in water. And when we die, the water leaves our bodies. Water is life.

Thunder’s authenticity is marvelous in his art, because all of his work is informed by the tapestry of Ojibwe culture. But instead of passively having his work be informed by Ojibwe culture, Thunder transports us inside the culture. Once there, he invites us to explore not just the culture, but his artistic commentary on the culture.

In this way, it’s an offering for the senses, the intellect, and the heart. Through this work, Thunder has proven that his art is not just a reflection of the colorful landscape of Ojibwe culture, but a creative force in itself that entertains, inspires and challenges us all.

Images from “Jonathan Thunder: Good Mythology” by Mara Films, LLC.