Where to start with Nam June Paik

“Skin has become inadequate in interfacing with reality. Technology has become the body’s new membrane of existence.”

— Nam June Paik, 1974

Composer, musician and video art pioneer

Nam June Paik was referring to the way that the emergent technologies of post-war America––portable video, television and live broadcasting––were swiftly altering the experience of human life. From the very beginning of his nearly 60 year practice, Paik was motivated by the tension between the liberatory and numbing potentials of technology. He observed how TV, largely controlled by corporations, was becoming a means of brainwash, but also how “talking back” to the media through informal networks and portable video could revolutionize art, social movements and global connectivity.

Born in Korea in 1932 to a wealthy family, Paik initially studied music and art history, writing his thesis on the Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg and receiving a BA in aesthetics from the University of Tokyo in 1954. In 1957, he moved to Munich, Germany to continue his studies in classical music, but more crucially, he met artists Joseph Beuys and John Cage, whose avant-garde artistic practices would inspire him to leave the conventions of his training behind for radical, often shocking, performances. For example, in Hommage à John Cage (1959), he interwove dissonant piano chords, screaming, bits of classical music and everyday sounds. In 1964, Paik moved permanently to New York, enmeshing himself within the experimental downtown scene, as well as becoming involved in Fluxus, an international movement of performance artists.

Paik would become known as the “father of video art,” practically inventing the concept through his work with TVs. In his writings, he prophesied ideas like the internet (an “electronic superhighway”) or YouTube (a “global video commons”) as early as 1974, predicting our current moment of hyperconnectivity. With characteristic wit and humor, his work continues to pose challenging questions about our relationships to technology and ourselves.

Here are five key works to introduce you to Paik’s varied contributions, with a particular focus on the ways that he processed his Asian heritage abroad.

1. Robot K-456 (1964)

A persistent theme across Paik’s work was to “humanize technology,” evidenced by how often he employed the human form in his video sculptures. But he was also interested in revealing technology’s indentured relation to human desire.

This dialectic is embodied in Paik’s first work to take the shape of a human, Robot K-456. Equal parts unsettling and pathetic, Paik’s robot is made out of bits and pieces of metal, old clothing, a data recorder, spindly legs with wheels for easy movement and a loudspeaker playing John F. Kennedy’s speeches. It was made in collaboration with with the Japanese engineer Shuya Abe, who Paik worked closely with to program the robot to walk, talk and defecate beans using 20 radio channels and a remote control. The robot was named after Mozart’s piano concerto No. 18 in B-flat major, K. 456 and in some ways one could see it as a extension of Paik’s deconstruction of classical music.

Robot K-456 reappeared in Paik’s subsequent performances in New York, perhaps most notably in 1982, when, on the occasion of Paik’s first major museum exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the robot was made to walk the sidewalks outside the building. The performance culminated in the robot being struck by a car driven by artist William Anastasi. Interviewed by the CBS reporter at the scene, Paik answered that he was “practicing how to cope with the catastrophe of technology in the 21st century.”

2. TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969)

When Paik moved to New York in 1964, he began working with the avant-garde cellist Charlotte Moorman, who would become a mainstay in his practice until her death in 1991. Moorman, who had trained at Julliard and was a former member of the American Symphony Orchestra, was drawn into the experimental art scene by her roommate, Yoko Ono. TV Bra for Living Sculpture consists of two miniature televisions attached to a set of vinyl straps that Moorman wore across her chest while she played a score composed by Paik. The television screens on her “bra” cycled between live television programming, prerecorded video footage and a closed-circuit camera’s live feed of the audience.

The performance was first produced as part of the group exhibition “TV as a Creative Medium” at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York, as part of a string of performances she collaborated on with Paik throughout the 1960s. These were not without their share of controversy; one of the performances ended in a police raid and the arrest of both Moorman and Paik. Today, Moorman’s performance remains an iconic, and complex commentary on the female body, live media and experimental music, as Paik would say:

“By using TV as bra ... the most intimate belonging of [a] human being, we will demonstrate the human use of technology, and also stimulate viewers, not for something mean, but stimulate their fantasy to look for the new, imaginative and humanistic ways of using our technology."

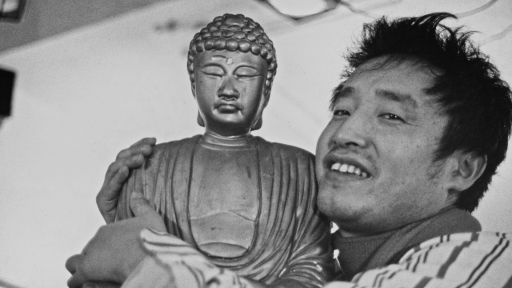

3. TV Buddha (1974)

Paik grappled with his Korean heritage in various ways throughout his career. Initially fleeing Korea to escape Japanese occupation, he was reintroduced to Buddhism, ironically, through John Cage’s interest in zen meditation while he was in Germany. Some of Paik’s earliest experiments with Fluxus sought to translate themes of Buddhism into new territory, like his 1961 Zen for Head performance, in which he dipped his head in paint and then drew a straight line evoking Asian calligraphy methods. Or his 1963 sculpture Zen for TV, which modified a TV set to display a quivering vertical line. Paik returned to these themes later in career, perhaps most famously in a sculpture titled TV Buddha (1974). Consisting of an 18th century Buddha statue (that Paik purchased on Canal Street) looking at a closed-circuit live stream of itself on a TV, the sculpture brought Paik near instant fame. He would go on to make several more Buddha works in various other configurations. Part of its fame perhaps had to do with its reference to the 1963 self-immolation of Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, who was protesting against the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government––the image was widely circulated through the 1960s. Paik’s work remains a koan-like1 reflection on mindfulness, media and protest at a time when US-Asia relations were shifting.

4. Global Groove (1973)

“This is a glimpse of the video landscape of tomorrow, when you will be able to switch to any TV station on the earth, and TV Guide will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book,” begins Paik’s seminal video work Global Groove, which was broadcast live from New York City’s public broadcast station WNET in 1973.

Since developing an analog video effects processor with Shuya Abe in 1969, Paik had learned to create collage and layering patterns on live television that had rarely been seen in public before. Working closely with WNET’s television engineer John Godfrey, Paik collaged various images from around the world: performances from avant-garde artists John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Allen Ginsberg and the Living Theatre; Pepsi commercials from Japan; Paik and Moorman performing TV Bra for Living Sculpture; pop dancers intercut with traditional Korean folk dancers, and much more. At one point, Paik presents “participation TV,” where he instructs the viewer to open and close their eyes.

As the US continued its war in Vietnam, Global Groove was conceived of explicitly as a colorful manifesto for connectivity, synthesizing Paik’s interests in east-west relations, cultural understanding and the merging of live arts and public broadcast, going on to influence a many decades of popular and avant-garde video aesthetics.

5. Electronic Super Highway (1995)

On June 22, 1984, after nearly 35 years of being exiled from his mother country, he returned to Korea. Although his initial experiments with Moorman had scandalized the Korean press, and even brought shame to his family, this time Paik was greeted like a national hero, mobbed by reporters at the airport. When asked why he took so long to come back, he responded wistfully:

“Life is but an empty dream."“Have you always felt Korean?” another reporter asks.

“Well depends on where I am,” he responds. “In New York, there are a lot of Koreans, so I felt like a New Yorker. But in Long Island there are fewer Koreans, so I became Oriental. And when I’m in Germany there are no Koreans, so I’m Korean.”

Perhaps as a factor of navigating so many different racializations throughout his life, Paik’s later work emphasized a vision for a globally interconnected world facilitated by technology. This was embodied perhaps most literally in the monumental sculpture Electronic Super Highway, which he produced in 1995 and consists of 336 televisions, 50 VHS players, 3750 feet of cable and 575 feet of multicolored neon tubing.

Each state depicts various media representations of itself: Kansas is represented by “The Wizard of Oz,”

Oklahoma has a feature on potatoes, his friend and mentor John Cage represents his idea of Massachusetts and Arkansas shows footage by performance artist Charlotte Moorman.

Paik was inspired by the US highway system, and made the work to foretell a future that feels all-too familiar now, in which the world might be connected via information pathways––a theorization nearly 20 years before the internet would arise. His utopian aspirations are infectiously earnest, particularly as his earlier work could be both pessimistic and futuristic; yet it remains an optimistic symbol of the best of what humans might be able to accomplish with technology.

1Editor’s note: A koan is a paradox or riddle, used in Zen Buddhism to demonstrate the inadequacy of logical reasoning and to provoke enlightenment.