Juanita Anderson’s director statement

“[It’s] like our existence as Black female creators is activism, and that’s kind of crazy.”

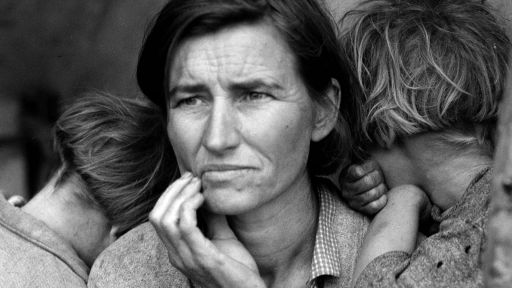

It was day three of filming with Sydney G. James in her studio, when she spoke those words in a way that seemed like a surprise to herself. She had made measurable progress on her new painting on canvas, “The Westside Johnsons,” based on an old family photograph of Sydney’s mother and her mother’s 11 siblings. It was an image Sydney had wanted to paint since she was a child. By now, Sydney realized that this painting would take significant patience, something that she professed was not her virtue, but very little painting would take place that day.

Sydney had invited her fellow artists and frequent collaborators, Sabrina Nelson and Scheherazade Washington Parrish, to join her. As the camera continued to roll, they had been engaged in nearly non-stop conversation–not only about the new work-in-progress, but about addressing the challenges they faced as Black women artists in an art world which still far too often ignored their existence. Keeping silent so as not to disrupt my observational camera process, I mused that Sydney’s utterance wasn’t crazy at all.

It’s who we are. It’s what we do. We create space– where others won’t — to enable us to do our work. And, in doing so we create space for more to enter.

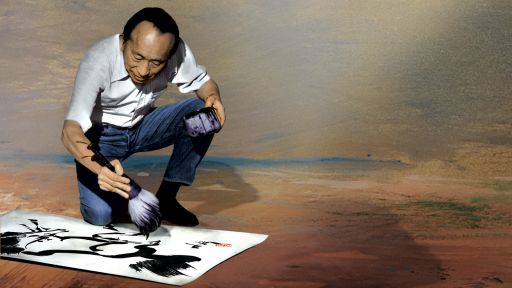

While I could go on about the many facets of Sydney’s process– the intricate patterning she creates as prelude to her murals, her preference for employing bold brush strokes, rather than spray paint on her murals, or the multiple layers of color she uses to render the distinctive pigments of Black skin, it is her process of space-making, which the public doesn’t see, to which I am particularly drawn.

Creating the 3500 square foot mural which honors the legacy of Malice Green, a Black man killed by Detroit police in 1992, and the “Way too Many,” who met similar fates was no small feat in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, and in the height of the Pandemic. To realize her urgent vision, Sydney launched a GOFundMe campaign, raising money to pay for equipment, paint and supplies, and most importantly for the artists who assisted her on the project. She donated the remaining funds to BYP100 (Black Youth Project 100), a national organization of Black youth activists whose work is “centered on ending systems of anti-Blackness and emphasizing the urgency of protecting folks living on the margins of the margins, including women, girls, femmes and the gamut of LGBTQ folk.”

The effort was preparation for her biggest space-making effort yet– raising funds from foundations and corporations; and the organizing, permitting and contracting undertaken by Sydney to bring the inaugural BlkOut Walls Mural Festival to Detroit in 2021. BlkOut Walls would not only create a space for 24 predominantly Black female, male and non-binary artists to create new work, it provided space for the community to engage with artists as they worked, and a lasting space for residents to interact and see themselves in a space that reflected Black life and culture.

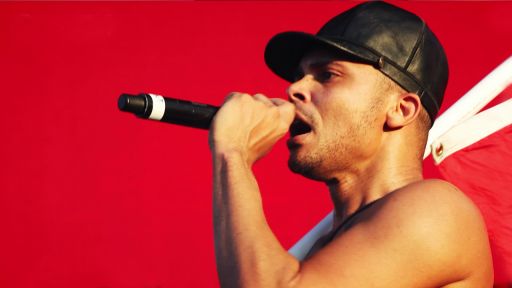

Her mentees, Bakpak Durden and Ijania Cortez, who collaborated with Sydney on both projects and who each created their own murals during BlkOut Walls, credit Sydney for teaching them the business of art. “We talk about processes, how to set things up, how to stay on task,” notes Ijania. Bakpak also credits Sydney with teaching them to research and use references in developing their work.

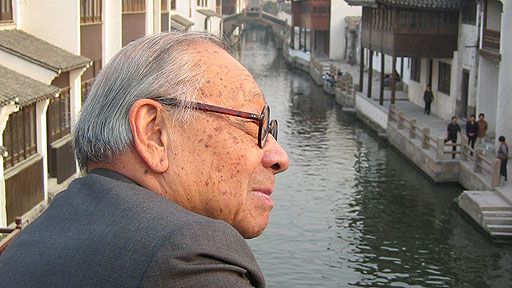

Indeed, for Sydney, creating space also means mentorship and she’s carrying on a long Detroit legacy of Black women creatives who have mentored emerging artists. They include Sydney’s own mentor, Marian Stephens, who appears all too briefly in the film. Stephens, who hails from a multi-generational family of artists and is a textile artist in her own right, was the Art Department Head and fashion design educator at Detroit’s Cass Technical High School where Sydney was a student in commercial art. When Sydney wanted to learn fashion illustration, Mrs. Stephens took Sydney under her wing and their relationship has continued to flourish ever since.

Sydney G. James’ 8,000 sq. ft. mural “Girl with the D Earring” (2020), Chroma Building, Detroit, MI. Photo by Lamar Landers.

“Marian Stephens provided me with creative nourishment I didn’t even know I needed at the time. She’s a large part of who I’ve become as an artist,” Sydney observed in a recent Detroit Metro Times interview.

“That’s what you’re supposed to do,” says Stephens in film footage that had to be left on the cutting room floor. “If you have a skill, if you keep it all to yourself, you’re not helping anybody. You’re not even helping yourself.”

As the camera continued rolling, Sydney noted that she is often asked what she considers her most important piece of work. Her response is, “ . . .honestly, the mentorship piece is probably my masterpiece if you will, because they’re now peers. You know what I mean?”

Indeed, 2022 has been a banner year for the mentees of Sydney G. James who appear in the film. Bakpak Durden opened their first solo museum exhibition at the Cranbrook Art Museum; and Ijania Cortez had a public unveiling of her new commissioned mural “To Whom Much Is Given,” which pays tribute to two of Detroit’s Black female iconic trailblazers in the arts.

Now both Bakpak and Ijania are poised to create new spaces, opening new doors that will further enrich Detroit’s creative community centered on ending systems of anti-Blackness and emphasizing the urgency of protecting folks living on the margins of the margins, including women, girls, femmes and the gamut of LGBTQIA+ folk.

About Sydney G. James

Sydney G. James is a fine artist/muralist raised in, and by, Detroit. She employs her fierce brushstrokes on canvas, fabric, brick and stone to provoke conversations, long silenced, on the ignored and invisible. Black women are first. Never last and never forgotten. Her figurative works boldly rewrite the narrative in hues evoking the complexities of Black reality, joy and pain, and phoenix-like resilience. Her murals have lit up walls in Detroit, New Orleans, Brooklyn, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Pow Wow Hawaii, Pow Wow Long Beach, Pow Wow Worcester, and across six continents. Sydney is a co-founder of the biannual BLKOUT Walls street mural festival, which debuted in Detroit in 2021. A 2017 recipient of the prestigious Detroit Kresge Artist Fellowship, she has been awarded residencies at Red Bull House of Art (2016), the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities (2020), and a 2022 International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) residency in Brooklyn, NY. James’ artwork has been featured by marketing brands Vans shoes, PepsiCo, Ford Motor Company, Detroit Pistons and Detroit Lions.

About filmmaker Juanita Anderson

Juanita Anderson is a filmmaker, photographer, media educator, curator and Detroit native whose work spans four decades in public and independent media. Her creative work lies at the intersection of cultural history, artistic expression and the responses to social injustice that amplify the voices of communities too seldom represented on screen. A seven-time regional Emmy winner, she is best known for her work as executive producer of the 1988 Academy Award-nominated feature film “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” (a film by Christine Choy and Renee Tajima), which garnered a duPont Columbia Silver Baton, a George Foster Peabody Award; and was inducted into the National Film registry in 2021. She was also the executive producer of the ITVS-commissioned series “Positive: Life with HIV; the Favorite Poem Project” video anthology, originally commissioned for the Library of Congress bicentennial, and the PBS/NBPC public affairs special, “Black America: Facing the Millennium,” which she also directed.

Named the 2019-2020 Wayne State University Murray Jackson Creative Scholar in the Arts, she is a 2022 Firelight Media Spark Fund recipient for her humanities themed work-in-progress, “Hastings Street Blues.” A career-long advocate for diversity in public media and the arts, Anderson was a co-founder of Black Public Media and is a past president of the National Conference of Artists, the nation’s oldest African American visual arts organization. In 2022, she was appointed to the American Documentary Board of Directors.