If the Buddha were here today, what would he do with television?

Nam June Paik answers with his famous TV Buddha installation of 1974: a statue of Buddha sits in meditation facing a television set; on top of the set, a closed-circuit camera points at the Buddha and feeds a live image of it into the screen. The work is simple and funny, yet, like Paik’s best work, allows multiple and contradicting interpretations:

Is the Buddha lost in its own image, entranced as we are by the magic of the closed circuit, a forerunner to the selfie?

Or is he skillfully using it for self-knowledge, as in Zen master Dōgen’s phrase, “To study the Buddha Way is to study the self?”

Is the piece a joke, cutting the gravitas attached to Buddhism? Or is it a reverential update to Buddhist art, Paik’s answer to the brush masters and sculptors of the past?

Paik had a fraught relationship to Buddhism. He was born in 1932 into a Buddhist family, but said in interviews that though he grew up near a temple, his father was focused on making money and his mother was more superstitious than Buddhist. And though he reportedly never smoked or drank in observance of Buddhist precepts, he thought the religion was backwards and fatalistic.

Paik’s 1958 encounter with John Cage in Germany—a figure who became central to his worldview and practice—brought him back to Buddhism. Cage, like many of his peers, was deeply influenced by the Zen Buddhism popularized by D.T. Suzuki and incorporated teachings of chance, no-self, and immediacy into his work.

“Zen has been dead for the last 300 years. Only salesman was alive,” Paik proclaimed in an undated typescript. “Two Americans [have] revived it. The first was Cage, using ‘electro-mechanical’ means and Timothy Leary, using ‘chemical’ means.” He added: “nobody has time to meditate 30 years in the mountain.” Paik is flippant, yet points to painful truths. At first, it seems he’s upholding a troubling narrative of the East’s self-caused decline and the West’s ascent as savior. But given Paik’s history, it seems he’s describing his own process of disillusionment and then return to Buddhism—like so many in the diaspora, Paik’s exile forces an unexpected confrontation with his home culture.

One thing Paik saw that his Zen-inspired artist peers didn’t was how Buddhists could be coopted, or corrupted, by political ideology. Growing up in Japanese-occupied Korea, Paik was forbidden from speaking Korean in public under threat of arrest; he knew the ravages of Japanese ideology firsthand. “To the disheartenment of young hippies…Japanese Zen monks played a leading role in war propaganda,” wrote Paik in a 1969 compilation of political comics and commentary.

He saw how the haiku, macrobiotics and other romanticized Japanese Zen forms were used in the service of nationalism—a nationalism that justified the brutal colonization of Korea.

Perhaps this cold-eyed awareness allowed Paik to bring the Buddha down to earth, without the exotification or unexamined reverence that marked much of the white counterculture’s Buddhism. Paik’s writings reference the famous case of a monk asking the great teacher Linji about the Buddha, and Linji replying that the Buddha was dried feces.

If Buddhism was to have any relevance for the era of “electronic superhighway” (a term Paik coined), it couldn’t float in a detached realm; it would have to engage the screen, the video camera and the rapid flow of information and image—the material realities of the day.

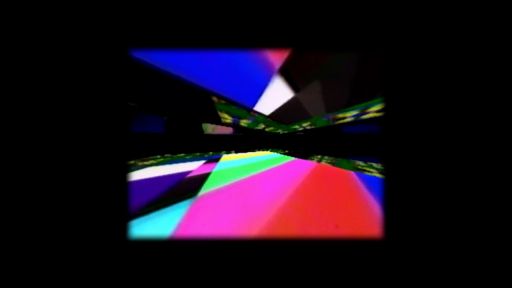

Paik made Zen for TV in 1963, five years after meeting Cage, when he turned from experimental performances towards video art. Television was the medium that would define Paik’s career and gain him global renown as the ‘father of video art.’ And while many of his best-known pieces are overwhelming and chaotic, with stacked monitors and dizzying colors, this early work is quiet and elegant.

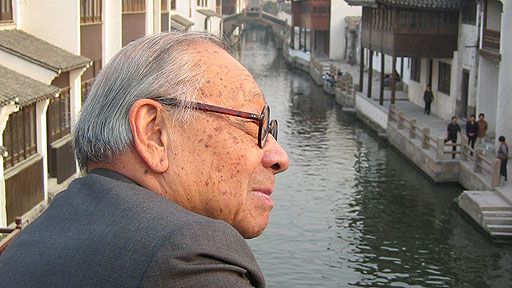

Installation view of TV Buddha at the Tate Modern.

Paik rewired the television so that a single white line bisects a dark screen. The effect is painterly: the image isn’t exactly static, as the light from the cathode ray tubes are constantly in motion, but it’s not a “moving image” in the filmic sense, either. Paik took the mechanics of the television and used them for something its creators never imagined, at once showing the power of the cathode ray and the void of the screen. The work recalls the famous line from the Heart Sutra: “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” It’s almost not a TV anymore, and that’s what makes it a great work of TV art.

Paik’s revolution was to break the sanctity of the screen, the one-way communication of the broadcast. “Television is a dictatorial medium,” said Paik. “I think talking back is what democracy means.” The dictatorship of the television was no abstraction for Paik—his 34-year exile from Korea was the direct result of the manipulation of information and image. Paik survived the Japanese occupation and fled the Korean war, then watched from abroad as Korea split in half and the North fell to authoritarian communism while the South to U.S.-backed military dictatorships. Like every child who discovers the magic of dragging a magnet across a TV screen and thus altering what seemed like an immovable force, Paik devoted his life to tinkering and altering those images, as if teaching us how to break its control.

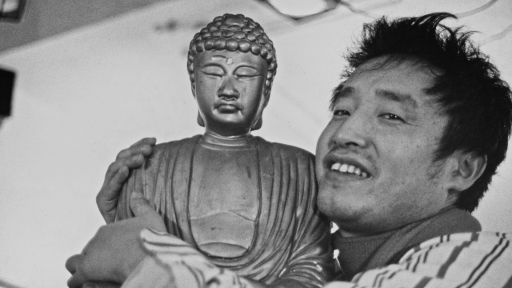

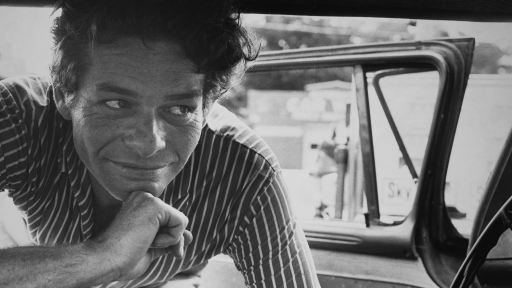

Nam June Paik with Buddha, 1967. Photo by Peter Moore, courtesy of Barbara Moore, Northwestern University.

One of the main questions of Buddhism is how to face the suffering of the world. Paik seemed to live with that question in every moment, driving himself into endless experiments and collaborations, generating countless works in many media. His answer, unlike many artists, was not in beauty— “newness is more important than beauty,” he said, and it’s hard to call many of his works beautiful, or even pleasant. Experimentation was his art; his relentless, optimistic quest to expand the limits and definition of communication were his answer to suffering.

Paik’s landmark Good Morning Mr. Orwell, a live variety show of avant-garde art that featured friends like Merce Cunningham and Laurie Anderson, broadcast on New Year’s Day of 1984 and reached an estimated 25 million people across America and South Korea, Europe and the Eastern Bloc. Despite technical issues, Paik considered the project a success. If only artists, rather than nations and corporations, could harness the TV’s power, perhaps we could use it not to control, but to astonish, to show us new possibilities.

If the Buddha were here today, what would he do with television? Paik’s TV Buddha shows us that he’s already here, both watching and broadcasting into the screen. What to make of this broadcast Buddha, and how to use that screen to face our suffering—Paik leaves that for us to figure out.