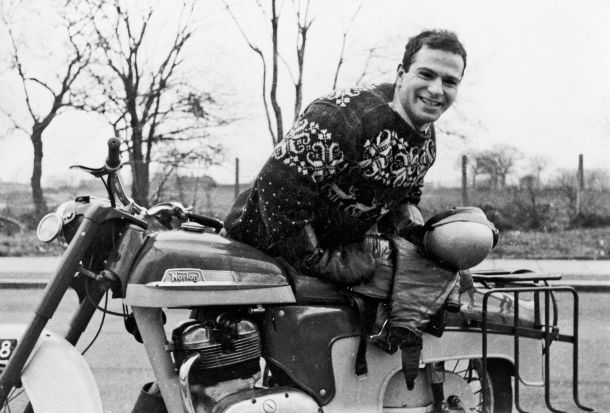

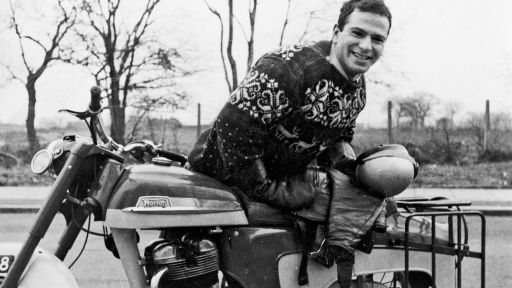

“I was alone. I found myself face to face with a huge bull – and started to run.” It was an overcast summer morning in 1974 when famed neurologist and author Oliver Sacks traded in his medical coat for hiking shoes. He was determined to summit a mountain in the Hardangerfjord in Norway.

The hike would ultimately lead to a dramatic run-in with a bull, a severely injured leg, a scrape with death, and finally, a revelation. But when it began, Sacks felt confident, exhilarated even, by the opportunity to hike on a quiet morning in Norway. He wrote in a 1984 essay for The New York Review of Books, “I foresaw no particular problems or difficulties. I was as strong as a bull, in the prime, the pride, the high noon of life. I looked forward to the walk with assurance and pleasure.”

It had been a long and trying year for the doctor. His trip to Norway was meant to be a time of healing and rest, an escape from the recent hardships he’d left behind in New York City.

The year before, Sacks had published the book “Awakenings,” in which he told the stories of patients he had worked intimately with, who suffered from encephalitis lethargica, or “sleeping sickness.” Sacks wrote “Awakenings” as a tribute to his late mother. He poured himself into his writing and by the time it was finished, Sacks was quite proud of his work.

Unfortunately, the book was not the raving success that Sacks hoped it would be. It failed to gain him credibility among his fellow doctors and scientists — who believed that Sacks was embellishing his patients’ stories. This reaction was a massive letdown for Sacks.

Around the same time, Sacks was working as a consultant one day a week at Bronx State Hospital. It was intense and often emotionally laborious. He recalled working “on a ward with youngsters who had autism, or childhood schizophrenia, or fetal alcohol syndrome. They had been warehoused together. This ward had a strong behavior modification philosophy that behavior could be changed by reward or punishment — especially punishment — and what they called ‘therapeutic punishment’ – isolating people, depriving them of food – gave me the shudders.”

Seriously disturbed by the hospital’s methods, Sacks shared his complaints at a staff meeting. He told his fellow doctors that he believed “the therapeutic punishment was cruel, useless, and maybe appealed to sadistic instincts in the staff.” Days after this confrontation, the ward chief told Sacks that a rumor was going around the ward that he abused the younger patients. He was asked not to return to Bronx State Hospital.

Sacks was not only devastated, he felt outraged and helpless. He even considered publishing a defamatory book about the hospital. Sacks later recalled, “It was in this mood of rage and guilt and accusation, that I went off to Norway in the summer of ‘74 – where I had a series of self-destructive accidents, culminating in my encounter with a bull on a mountain, and badly injuring my leg, and almost ending my life.”

It was dawn when Sacks embarked on the hike on that fateful day in Norway. He was hiking alone and there were no other people in sight. He appreciated this isolation at first, content to have the “whole mountain to myself,” as he wrote in his 1984 essay, “The Bull on the Mountain.” He planned to reach the summit by noon, hoping that by then the cloudy skies would clear and he would stumble onto a spectacular view of the town below him.

Around 10 a.m., he came across a sign that read in Norweigan, “BEWARE OF THE BULL!” Below the bizarre and cryptic warning was a picture of a cartoonish bull hurling a stick person over a cliff. Sacks marveled at the sign, perplexed. What would a bull be doing near the top of a mountain? He decided the warning must be a joke and continued on his way without much thought.

About an hour later, Sacks recalled coming upon “a boulder as big as a house,” as he wrote in “The Bull on the Mountain.” The hiking path snaked around the enormous boulder, but it blocked the view of anything beyond it. As Sacks continued onward, he had no idea that a giant white bull was sleeping just a few feet away.

By the time he saw the massive creature, he was nearly tripping over it. Sacks remembered in his essay that, “it had a huge horned head, a stupendous white body, and an enormous, mild, milk-white face. It sat unmoved by my appearance, exceedingly calm, except that it turned its vast white face up toward me. And in that moment it changed before my eyes becoming transformed from magnificent to utterly monstrous.”

Sacks, afraid for his life, bolted down the mountain – running so hard and fast he mistook his own footsteps for that of the raging bull, who he was convinced must be chasing after him. He ran with all his might – until he slipped and tumbled downward, landing with a thud near a rocky cliff. His left leg was twisted beneath his body, and Sacks was writhing in unimaginable pain.

Sacks performed a brief examination on himself and determined that his quadriceps were completely ruptured in his left leg. His muscles were paralyzed, indicating nerve damage, and his knee was dislocated. Incredibly, Sacks crafted a make-shift cast out of an umbrella he carried with him, and was determined to get himself down the mountain. If he didn’t, he feared he would never be discovered, and knew that he would never survive.

With his leg in the umbrella cast, Sacks slid his body, in a sitting position, down the mountain. There were multiple times when the slope was especially steep and Sacks was unable to control his speed. In those times, he landed with a crash at the bottom of the incline, exacerbating his injury (and his pain).

Sacks also had to navigate a stream with a heavy current. He had struggled to cross the stream on his way up, with both legs working, and was terrified that this might mean the end for him. He described in his essay: “The water was fast-flowing, turbulent, and glacially cold, and my left leg, dropping downward, unsupported, out of control, was violently jarred by stones on the bottom.” He managed to pull himself across against all odds.

By the time he arrived again at the bull warning sign, he realized that he was still hours from the bottom of the mountain. He checked his watch. It was 6 p.m. The shadows were growing longer beneath the setting sun. With a mixture of horror and utter disbelief, Sacks realized that he had been slithering down the mountain for seven excruciating hours. He wrote, “thus what had taken me little more than an hour to climb, had taken me, crippled, nearly seven hours to descend.”

Sacks knew that he had no chance of making it down the mountain before nightfall. Still, he continued to drag himself down and down and down, stopping intermittently to fight exhaustion and check his makeshift umbrella splint. It was while he was resting that he suddenly heard the voice of a man and his son, just yards away. A pair of hunters were on the prowl for reindeer. They heard something move and thought it might be their prey – but instead found Sacks, on the brink of death, on the side of the mountain. And with that, Sacks was saved.

Unfortunately, Sacks’ rescue was just the beginning of a long and agonizing recovery. Shortly after undergoing surgery in London, Sacks noticed something peculiar about his leg. “For two weeks or more,” following the surgery, “I could neither move nor feel the damaged leg. No information was coming from the leg to my brain and none could be sent. I had lost the sense of ownership. It felt alien, not a part of me, and I was deeply puzzled, confounded.”

The only time that Sacks felt like his leg belonged to him was when he played music. With music playing, Sacks’ leg was able to move, to stand, to walk, as if it was actually reacting to it. At the same time, while Sacks’ leg remained numb long after his cast was removed, he discovered that when he swam (a favorite sport of his before the injury), the leg moved normally, instead of with a limp.

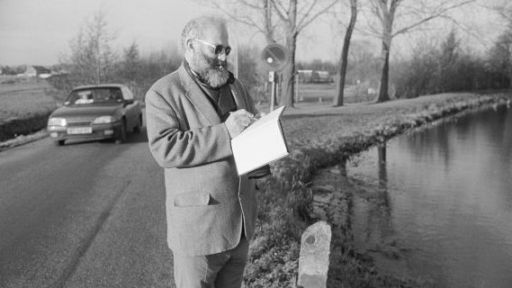

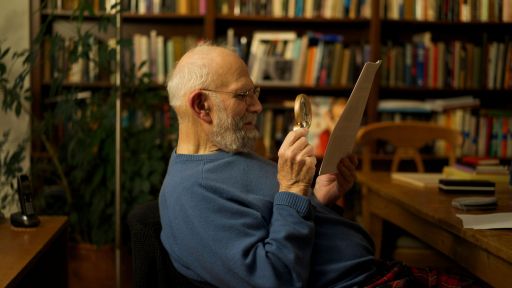

Fascinated by his findings, Sacks wrote “A Leg to Stand On,” which took eleven years to finish and publish. Sacks recalled that the book, “was tremendously difficult to write,” because for the first time in his career Sacks himself was the patient in question, the subject of the case study. It was a deeply personal account.

In the end, “A Leg to Stand On” was met with critical acclaim. It combined neurology with poetry, a unique opportunity for readers to learn about the body and mind from a scientific and emotional perspective.

In the end, the bull may have given Sacks just the push he needed. He had left for Norway to escape the chaos and pain of life at home, and was at first grateful for the isolation he found on that mountain, but by the time he was rescued he was glad to re-enter the world again. “I was back,” he wrote in “The Bull on the Mountain,” “God be praised! [Back] in the good world of men.”