Tonight, I am making banh chau for a dinner party.

Though my mother taught me the recipe, I know that what I cook, given the same ingredients, will taste completely different from her original flavors. I worry that the fish sauce is too sweet, so I add lime juice and water. As I throw bean sprouts into the sunny batter frying in the pan, I accept that I will never be able to make her version of banh chau.

As a child of Khmer refugees I seem to cook in the same way that I speak slang, which allows me to stay in lineage with my ancestral taste buds while flailing into new creations.

On my travels, I have been lucky to taste Cambodian dishes by many chefs in my generation. Oakland, Stockton, Long Beach, Philly, New York City, Revere, Lowell. I have eaten from their farmers market stands, food trucks, pop-ups, restaurants, takeout windows, and informally, at their backyard barbecues after house blessings. Though I always compare their dishes to my mother’s unparalleled cooking, I also look for textures or techniques that might arouse my palette beyond the familiar. Every Cambodian American chef feeds us their forward vision of Cambodian cuisine influenced by the region where they grew up as kids without blueprints.

When I consider Cambodian culinary futurism, I turn to the relationships that taught us to be resourceful: the one that we have with the land on which our elders resettled as refugees and the ones that we have with our beloved matriarchs who taught us the ultimate love language of cooking.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

In my mother’s unruly garden, I find potted lemongrass and garlic, mint and red chilies growing on the side of the house that meets the driveway, fish cheek herbs and scallions next to prickly roses, and a banana plant that doesn’t fruit in Pennsylvania’s temperate climate. In her yard, persimmons and Asian pears are scattered. She is preparing prahok, covering the container with a heavy cinder block so that the neighborhood cats will not paw at the fermenting fish. In the distance, cornstalks rise, and Amish horses and buggies clop along the road near cows chewing on grass. The land surrounding her home and her garden mirror abundance, as the wind chimes sing a song every time the wind cartwheels.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

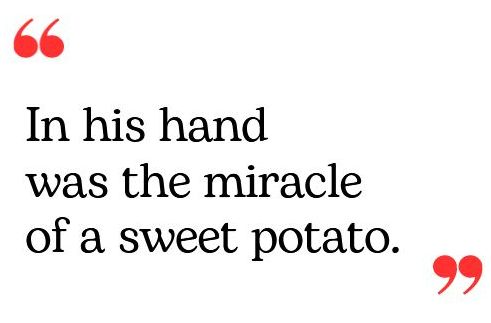

Before my grandfather died, he gave my mother a sweet potato. Her eyes light up while cherishing the memory of his last gift but gradually darken from the timing of his loss. A few months before Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia, effectively liberating the country from the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, he died of forced labor and starvation. If only he could have held on longer, he would have seen a new day. My mother has told me this story many times. I always wonder how my grandfather, in a time of scarcity, found food to give his children on his deathbed.  In his hand was the miracle of a sweet potato. A root vegetable to propagate in soil that could feed a whole community. A small seed of resistance against an oppressive regime. A future in which my mother could live. Early on, after the Khmer Rouge established its power and evacuated Phnom Penh to the provinces, he had already experienced the death of an infant grandchild due to the lack of food that malnourished his eldest daughter’s ability to produce breast milk. Perhaps, the sweet potato was also a prayer for his future grandchildren.

In his hand was the miracle of a sweet potato. A root vegetable to propagate in soil that could feed a whole community. A small seed of resistance against an oppressive regime. A future in which my mother could live. Early on, after the Khmer Rouge established its power and evacuated Phnom Penh to the provinces, he had already experienced the death of an infant grandchild due to the lack of food that malnourished his eldest daughter’s ability to produce breast milk. Perhaps, the sweet potato was also a prayer for his future grandchildren.

Because of my grandfather’s memory, I am careful to not overwork myself in this country that dropped 2,756,941 tons of bombs in Cambodia, more than the total figure that the Allies dropped during World War II.1 If I’m hungry, I eat. If I’m tired, I rest. I feel his inexorable hope when I hold a sweet potato in my hand at the grocery store.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

In the 1980s, my mother and her family resettled as refugees in Pennsylvania. When I visit Lancaster, where I was born and raised, my father grills a whole fish. I pluck mint and fish cheek herbs with my mother. My aunties bring fresh cucumbers grown in their own gardens. We pick from the same platter and bundle bits of fish and herbs inside lettuce, then dip it in fish sauce, sprinkled with crushed roasted peanuts and slivers of red chilies. The day I leave, my mother bags mint from her garden and tells me to stick the sprigs in water until they grow roots, then plant them in soil.

A daughter of farmers, she was born in Takeo, a province that suffered from Nixon’s Operation Menu bombings during the war in Vietnam. With her family, she left her village of Chambak for safety and later returned home to find fish fried in the pond. I cannot begin to comprehend the devastation of the land and all the land mines still burrowed in the ground. For the last forty years she has lived outside of her homeland. She takes pride in her garden and laughs when the rabbits eat all the kale. She feeds those who share the land, and in return the land feeds her.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

The last time I ate at a restaurant in Lowell, I heard people outside of my community order dishes in Khmer. Is the amok popular? Would you recommend the samlar ktiss or the samlar korko? We’d like the smoked eggplant, troub trung kor. A menu that makes Americans speak Khmer? That’s a future I didn’t know already existed. Like our Thai and Vietnamese counterparts, I wonder when Cambodian restaurants will increase all over the country so that our cuisine is just as familiar as pad Thai and pho. Will the funk that is familiar to me become familiar to Americans? Will they prefer a watered down version? Will they seek the spots where Cambodians are the main crowd?  I admire Thai restaurants that post unapologetic signs, bluntly stating that they will not issue refunds if their customers can’t handle the heat. They do not tone down their spices in the same way that I hope Cambodian American chefs do not feel the pressure to tone down their funk. As far as the audience is concerned, I hope that our cuisine does not so much prioritize non-Cambodian diners to suit their palettes as much as become available to them. Having grown up in a small town without Cambodian restaurants, it is always special to be served by a Cambodian American chef who treats me as the main audience and is just as happy to see me as I am them.

I admire Thai restaurants that post unapologetic signs, bluntly stating that they will not issue refunds if their customers can’t handle the heat. They do not tone down their spices in the same way that I hope Cambodian American chefs do not feel the pressure to tone down their funk. As far as the audience is concerned, I hope that our cuisine does not so much prioritize non-Cambodian diners to suit their palettes as much as become available to them. Having grown up in a small town without Cambodian restaurants, it is always special to be served by a Cambodian American chef who treats me as the main audience and is just as happy to see me as I am them.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

As a writer of diaspora, I envy chefs. Embedded in their craft is the language of food that our elders speak, no translation necessary. Whereas I write in English and not in Khmer, Cambodian American chefs can use the precise ingredients that our early ancestors used, evoking a sense of home in their own style. Though I am not fluent in Khmer, I still hope that my ancestors will understand my feelings in another language. However, if they were to dine at a Cambodian American restaurant, they would surely recognize kreung in any form or other ingredients they remember from their time on earth. Memory and nostalgia play a part in generational culinary slang as does the rule-breaking that gives today’s chefs permission to become bold in their creativity. Gaining the approval of our elders is hard won, and yet I am positive that they, too, rebelled against rules that their own elders imposed on them. Though our funky ingredients are the words I wish I had, I’m inspired to relax into my own creative process when I see Cambodian American chefs fire up new concepts. Their cooking is the medium between the homeland and our ancestors and how each manifests in Cambodian American life.

Chef Ethan Lim and Momma Lim host a multi-course tasting menu dubbed “Family Meal.” Watch Ethan Lim: Cambodian Futures

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

The centerpiece of every feast is my family. The time I share with them nourishes me as does my mother’s garden. Though I try to cherish the present, I often wonder how the trajectory of Cambodian culture would have blossomed had the country flourished in peace.

The centerpiece of every feast is my family. The time I share with them nourishes me as does my mother’s garden. Though I try to cherish the present, I often wonder how the trajectory of Cambodian culture would have blossomed had the country flourished in peace.

If the war had not happened, how would Cambodian cuisine have evolved in our parents’ generation? Before Pol Pot Time, what if there was a rising chef in Battambang who dreamed of new desserts that we will never know? Fast forward to Khmer Rouge regime survivors in the immediate aftermath of genocide. Would this question have had any meaning for them? The war had happened, and I cannot forget that people like my grandfather had died of starvation. To our elders, culinary futurism may mean the abundance of food and the preservation of our traditional cuisine, but the chefs of my generation are privileged with time, and I have faith in them to experiment with wild abandon.

Images from Ethan Lim: Cambodian Futures, a film by Dustin Nakao-Haider.

1 https://thewalrus.ca/2006-10-history/