What first got you interested in doing a film of Glenn Gould?

Peter Raymont: As a child growing up in the 50’s and 60’s in Canada’s capital city, Ottawa, Glenn Gould’s music was always in our home – on radio, on gramophone records my parents had – and my mum and Dad loved playing the piano. One of my earliest memories is waking up to the sound of my father playing the piano. I took lessons of course but often resented having to practice while my friends were outside playing football or hockey. So Glenn Gould, and Marshal McLuhan, were very much part of my consciousness as a young Canadian boy.

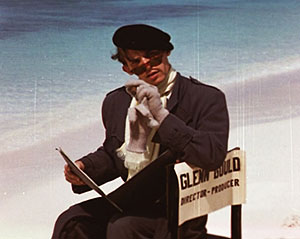

As a filmmaker I thought that all the films about Glenn Gould that could be made, had been made. There were the two National Film Board of Canada classics, Glenn Gould On the Record and Glenn Gould Off the Record, and there was Francois Girard’s popular Thirty-two Short Films About Glenn Gould, and several others. But then I met Michael Clarkson, a journalist with The Toronto Star newspaper, who had just interviewed Cornelia Foss, wife of the great American composer, Lucas Foss. Cornelia told of her long love affair with Gould, how she separated with her husband and moving to Toronto with her two children to marry Gould. I met Cornelia in New York who agreed to be interviewed for our film. That convinced me that there was a whole other film to be made about Glenn Gould, revealing for the first time his personal, private life, but done in a respectful, non-prurient way.

Michele Hozer: When I was approached by Peter Raymont to co-direct, I immediately agreed because I knew Gould would, like all good mythical figures, be a fascinating, complex and contradictory character to explore. At the same time, there was something about Gould that made him the classic tragic hero. Through him one can explore the greatest virtues in humanity, but also the darkest of fears and flaws—in other words, that which makes us fundamentally human, in all our triumphs and frailties.

When did you first become aware of Glenn Gould?

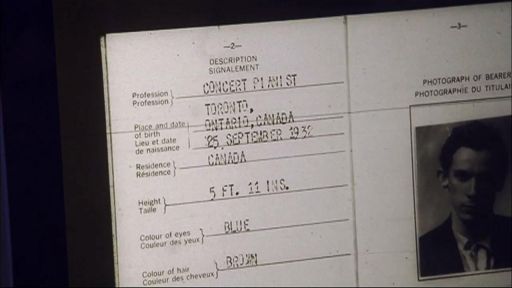

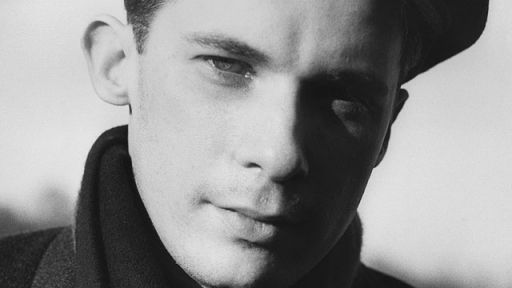

Peter Raymont: Glenn Gould was part of my consciousness from the beginning of my life (see above), but I only knew of his extraordinary skills as a pianist and interpreter of Bach, and as a reclusive, though handsome genius. Gould’s inner life was a mystery.

Michele Hozer: When I originally learned that Peter Raymont was developing a film about Gould, I, like most Canadians knew the standard shorthand about this cultural icon: great pianist, but a rather odd and shadowy personality. I owned a copy of the Goldberg Variations and was a fan of “32 Short Films about Glenn Gould.” But, frankly, I knew little about Gould the man, even if I had an interest in him as an almost mythical character.

While making the film, did you learn anything that surprised you about the subject?

Peter Raymont: It was wonderful to talk with Cornelia Foss’s children, Eliza and Christopher and discover what a wonderful father-figure he was for them when they lived near him in Toronto for four years. He loved children, and animals, but sadly never had children of his own. It was also wonderful to be able to see that, while he was undoubtedly a musical genius, he was also very much an “ordinary” man who was desperate to be loved and to love others.

Michele Hozer: What surprised me the most about Glenn Gould was his wonderful sense of humour. Not necessarily something you expect from a classical musician. Gould was a type of character who loved to put on costumes and play different characters with funny voices. As his biographer Kevin Bazzana puts it “. . . he provides some relief from the conservatism of the classic music business.”

Are there any interesting anecdotes about the filming or the interviewees?

Peter Raymont: It was wonderful how people opened their hearts to us and wanted to share their most intimate stories of Gould. Michele did almost all the interviews.

Michele Hozer: One interesting outcome of this film is meeting Cornelia Foss’ children Christopher and Eliza Foss and learning of their relationship with Gould. When they were young children they spent 4 years in Toronto with their mother and Glenn. Both Christopher and Eliza speak very fondly and warmly about their time with Gould showing us a side of him know one ever knew. One that was generous and caring of young children, which makes Glenn even more endearing.

Please describe your approach to the film.

Peter Raymont: We wanted to peel back the layers of artiface and spin that Gould and his handlers had constructed around him, and find the real human being beneath all that glitter and hype.

Fortunately Gould kept a diary and letters which were revelatory and fortunately some of his most intimate friends were ready to speak to us. Michele co-directed and edited the film and found a way to weave the vast array of archival footage with interviews and music into a lively tapestry that moves along at a good pace for 112 minutes.

Michele Hozer: Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould uses an array of archival material, TV footage, film clips, musical performances, and original footage and interviews to celebrate Gould’s art and life. It is a celebration of the diverse body of work he produced and a study of the genius behind the man who always expressed himself in layers. Gould himself is the guide, with insights from those closest to him, leading us through the labyrinth of thoughts, dreams, and desires of a true enigma.

Gould’s most intimate friends have chosen this opportunity to address the myths and misconceptions that have built up around the indomitable pianist. These charismatic characters recount their vivid memories of Gould and we gain a unique perspective into the life of such an intensely private man. Apart from Gould himself, no one else is better able to shed light on his fears, aspirations, and dreams than those who lived beside him and worked with him.

What were some of the obstacles in achieving your vision of the film?

Peter Raymont: Fundraising is always an obstacle to the creation of a feature-length theatrical documentary. Fortunately there are broadcasters like BRAVO in Canada, PBS-American Masters in the U.S., ARTE and SVT in Europe and other sources of private and public funds in Canada that made it possible.

Once the funding is in place, the major obstacle was finding the through-line that would hold all the rich archive footage together. Michele Hozer is a master editor and storyteller, and she did an extraordinary job.

Michele Hozer: From the beginning, it was a challenging undertaking. Gould has not one but five biographies, with others in the works. Also, since his death in 1982, there has been numerous film exploring his life and achievements. So, the basic question: what do we have to offer that’s new? Why yet another film about Gould?

Like Gould himself, the answer is complex. At the heart of it all, Gould is a great human story. By intimately looking at the man along side the myth, not only do we understand a bit more about Gould, we can all understand a bit more about ourselves, about our society. We can all relate to wanting to achieve success, to make our lasting mark in some fashion, but is there a human cost, a personal sacrifice, and is it ultimately worth it all? No simple answers but fundamental and worthy existential questions to ponder.

Gould often talked about the transcendental nature of music; maybe by losing ourselves in his music and his story, we can better find ourselves, or that’s my hope.

Please describe your background credits, how maybe they led to this film.

Peter Raymont: I’ve been making documentary films for 39 years, initially as an editor working at the National Film Board of Canada and then with my own company, which I founded 32 years ago. Most of my films have been in the area of human rights and social justice (Shake Hands with the Devil, chronicled the horrific days of the Rwanda genocide through the eyes and experiences of the commander of the UN peacekeeping troops, and was awarded the Emmy for Best Documentary). But as I get older (age 60 this year), I find myself attracted to making films about artists, and others who stretch the limits of human potential.

Michele Hozer: A good filmmaker is ultimately a great storyteller.

As a documentary editor for over 20 years I have been very fortunate to work on films that were made in the edit room.

Unlike fiction films, a documentary editor does not work with a script. Usually the editor has hundred of hours of footage to go through, and slowly, often painfully, the story is found.

In some way, the transition from editor to director was a natural transition. In fact, my co-director Peter Raymont also started his stellar career as an editor.

Together we have worked on films such as Shake Hands with The Devil: The Journey of Romeo Dallaire and A Promise to the Dead: The Exile Journey of Ariel Dorfman, whose characters and experiences offered us a wealth of material with which to craft important and universal stories.