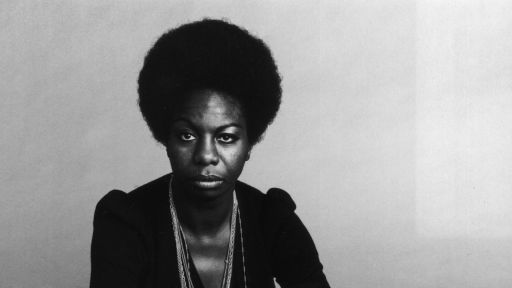

It was a bloody Sunday in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963 that inspired the singer and pianist Nina Simone’s famous protest song, “Mississippi Goddam.” Four young Black girls died that day in a white supremacist terror attack that would become known as the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. But the incongruously upbeat show tune wasn’t just crying out about this sole event. Simone was also lamenting the recent gunning down of civil rights activist Medgar Evers in Mississippi. She was voicing anguish about all the acts of violence and oppression against Black communities in the segregated South. She was weaponizing music itself.

“At first I tried to make myself a gun. I gathered some materials. I was going to take one of them out, and I didn’t care who it was,” Simone famously said after hearing of the Birmingham bombing. “Then Andy, my husband at the time, said to me, ‘Nina, you can’t kill anyone. You are a musician. Do what you do.’ When I sat down the whole song happened. I never stopped writing until the thing was finished.”

The end result, composed in under an hour, would become her first battle cry for the civil rights movement. “It was my first civil rights song,” she later recalled, “and it erupted out of me quicker than I could write it down.”

“Alabama’s gotten me so upset // Tennessee made me lose my rest // And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam,” Simone sings in the song’s opening line. Writing and performing it felt “like throwing ten bullets back” at the four Ku Klux Klan members who planted the dynamite, she said.

Actual justice was agonizingly slow for the victims and community affected by the bombing. One of the Birmingham perpetrators wasn’t convicted until 14 years after the attack and two others weren’t jailed until more than 38 years later. The fourth died before being charged.

Simone’s protest anthem addresses the general sluggish pace of change and justice in America: “I don’t trust you anymore // You keep on saying ‘Go slow!’ // Go slow! // But that’s just the trouble.” She also addresses the fears surrounding a biased criminal justice system that could easily be transposed to racial injustices that are still being protested against today: “Hound dogs on my trail // School children sitting in jail // Black cat cross my path // I think every day’s gonna be my last.”

“In Mississippi Goddam, we have Nina Simone pulling from the past and invoking it in the present, but also speaking to what is yet to come if America does not enact real social change,” said musicology professor Tammy Kernodle.

The song’s stinging lyrics subvert the lively, up-tempo refrains of the melody itself – seemingly a commentary on America’s eagerness to ignore or wallpaper over the pain of racism and segregation. The (mostly white) audience who heard the show tune as it was being recorded live at Carnegie Hall did not seem to get the message at first. At the start of the performance when Simone announces, “The name of this tune is Mississippi Goddam, and I mean every word of it,” the crowd titters and laughs. In the middle of the recording when she addresses the crowd again with, “Bet you thought I was kidding didn’t you?” Her question is met with only a few murmurs.

Then there were those who protested the protest tune. “We got several letters where they had actually broken up this recording and sent it back to the recording company, really, telling them it was in bad taste,” Simone said during a 1964 interview on the Steve Allen Show. “They missed the whole point.”

In the years after she first penned the song, Simone changed the lyric, “Tennessee made me lose my rest,” several times during various live performances around the country and the world. On the same 1964 episode of Allen’s show, Simone swapped the line for, “St. Augustine made me lose my rest,” in honor of the civil rights movement that took hold in that Floridian city. A year later, she sang for “Selma,” after the brutal police confrontation with peaceful marchers across Alabama’s Edmund Pettus bridge in 1965, and later that same year for “Watts,” when riots broke out over six days in that Los Angeles neighborhood. Simone then mourned that, “Memphis made me lose my rest,” after Martin Luther King was assassinated there in 1968.

“An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. That to me is my duty,” Simone said in an interview with Black Journal. “And at this crucial time in our lives when everything is so desperate, when every day is a matter of survival, I don’t think you can help but be involved.

“Young people, Black and white, know this. That’s why they’re so involved in politics. We will shape and mold this country, I will not be molded and shaped at all anymore.”