By Liz Fields

Laura Ingalls Wilder may have poured out her life story into the pages of her “Little House” books, but she was a woman who kept secrets. One of the biggest was her working partnership with daughter Rose Wilder Lane, which for whatever reason, the women chose to keep hidden from the world. The collaboration was only confirmed years later by historians combing through a trove of letters between the two. The correspondence not only revealed the extent of Lane’s hand in editing and structuring her mother’s writing, but also their shared political views. Those views invariably made their way into the eight-book series for children, although most young readers probably haven’t observed this subtle political messaging.

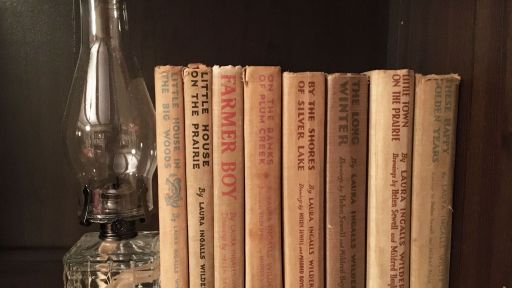

Wilder first conceived of the “Little House” series in her mid 60s, during the time of the Great Depression. The first novel, “Little House in the Big Woods” was published in 1932 — the same year that Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to the White House. Soon after taking office, FDR set about enacting a series of financial reforms and public projects and programs designed to help pull Americans out of economic devastation and expand the government’s role in the economy, much to Wilder’s despair.

“I think Laura Ingalls Wilder’s early poverty and deprivation in some ways challenged her to work hard, use her talents, and give 120 percent effort to edge them into middle class somewhat security,” said biographer and historian William Anderson, who authored “The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder.”

“The ‘Little House’ books stressed self-responsibility, community cooperation, taking care of one’s needs oneself, and with these goals, a person could be free and independent,” he said.

Other scholars agree that the hardships that the family faced throughout their lives contributed to both mother and daughter’s distaste for what they saw as federal interference and handouts.

“They both were sort of physically ill over FDR and the New Deal,” said Christine Woodside, author of “Libertarians on the Prairie.” “They felt that it was just a really inappropriate response to hard times. They had seen hard times. Why did the government want to help people? And Laura thought that everybody was starting to whine in response to the New Deal. She just couldn’t stand it. It made her sick.”

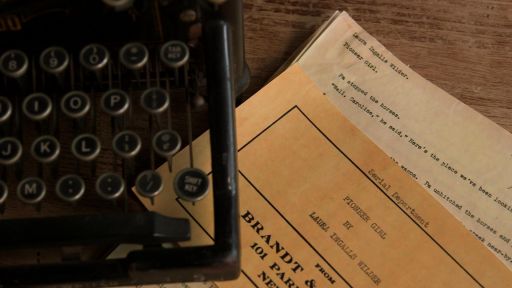

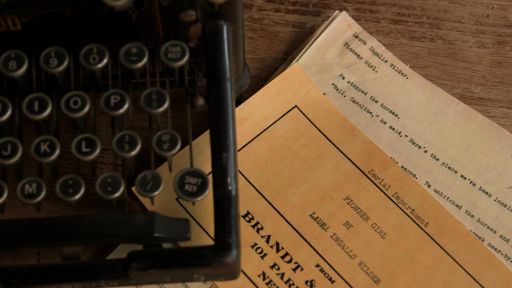

These politics are on full display in this 1934 letter that Wilder wrote to a book editor at Harper’s:

“The Lord give me patience! How exasperating a bunch of communists in Washington can be! I suppose all we can do is await their pleasure. Give them time enough and they will put us all on the Federal payroll or the relief.”

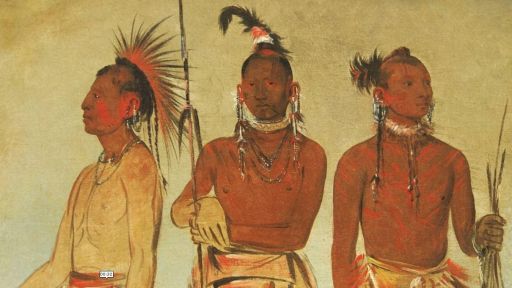

Although the “Little House” books are littered with stories about the family’s ability to beat obstacles through self-reliance, the reality was not always so rosy. In fact, Wilder and her family had benefited from a farm loan as part of a federal program received while she was working at the Mansfield Farm Loan Association. In the books, Wilder also describes the family settling in virgin territory untouched by people. But they had, in fact, knowingly moved in on Native land that was protected by none other than the federal government, which stationed soldiers in the Dakota territory to safeguard settlers from Native American attacks and provided aid after natural disasters.

“It’s very clear that she wanted to believe her own fiction. You know, she began trying to sell it as the truth,” said biographer Caroline Fraser.

It’s difficult to tell who had more influence in infusing the books with this type of ideology. Some believe that it was in fact the author’s only child who was responsible for some of the more overt political passages in the books.

Lane, a successful author in her own right, was renowned for her “yellow,” sensationalist journalism that became increasingly political in nature throughout her career. Her work included many essays that touted individualism and spoke out against handouts and taxation. But after FDR’s election, her writing took a distinct turn. According to the New Yorker, Lane wrote in one particular diary entry that, “America has a dictator,” and prayed for the president’s assassination. In a 1936 essay for the Saturday Evening Post she declared: “I am now a fundamentalist American.”

Today, Lane is considered one of three founders of the modern American libertarian movement, along with the prominent female writers Ayn Rand and Isabel Paterson. She was considered, “sort of a rock star, in today’s slang, to the libertarians,” said Woodside.

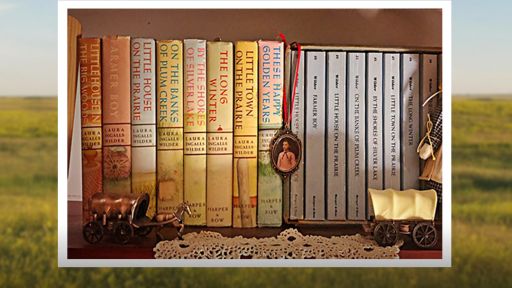

The last two “Little House” books in particular bear some of the marks of Lane’s political writings. For example, this passage from “Little Town on the Prairie”:

“She thought: Americans won’t obey any king on earth. Americans are free. That means they have to obey their own consciences. No king bosses Pa; he has to boss himself.”

“Many of us, myself included, did not realize the political undertones to much of the series and did not understand the ways in which political messages were put into dramatic scenes,” said Woodside. “I think that for Laura it was absolutely not conscious at all. I think for Rose it was her idea of what is truth. So, in that sense, it wasn’t conscious either; it was Rose being Rose.”

Fraser agrees that it’s not the politics, but the prose itself — the vivid description of character and time and place — that generations of young readers cling on to.

“Part of the joy of reading the books is their emotionalism,” she said. “And that’s what keeps people coming back to it. It’s not because they’re political texts. It’s not because they have something to say about, you know, pulling yourself up by your bootstraps — although they do. But that’s not why people read them.”