On Fat Tuesday in 1949, the last day of the carnival season in New Orleans, thousands of exuberant parade-goers swarmed the streets to get a look at the “King.”

The excitement of the crowd was palpable – little boys clutched toy trumpets, women and men fought for a coveted spot at the front of the line, little girls climbed upon their father’s shoulders to get a better view. This wasn’t just any Mardi Gras, for that day, Louis Armstrong, the king of jazz, would reign as the Zulu King.

“There’s a thing I’ve dreamed of all my life,” Armstrong told Time magazine in 1949, “and I’ll be damned if it don’t look like it’s about to come true – to be King of the Zulu parade. After that, I’ll be ready to die.”

The dream to lead the parade began when Armstrong was a small boy growing up in Jane Alley, a Black neighborhood that had been sorely neglected by the city. It was known as “The Battlefield,” because of the violent fights and drunken brawls that would break out in the darkness of night.

Armstrong’s life in Jane Alley was lonely – his father left shortly after he was born, and his mother was forced into a life of prostitution to pay the bills. Armstrong himself quit school in fifth grade so he could work. He found a job delivering coal and selling junk for a local family, the Karnofskys.

Beginning when Armstrong was nine, though, there was something he had to look forward to. Something that made his pulse rush, his eyes light up, his hands sweat in excitement, he happily recalled to Time magazine. That event was the Zulu parade, which first wound its way through Armstrong’s own neighborhood in 1909.

The Zulu parade was first started by a group of prominent working-class Black men – ranging from dock workers to bartenders to wagon drivers – who banded together to hold their own version of Mardi Gras. They named it the Zulu parade as an homage to the Zulu people of southern Africa, who had once chased British colonists out of their villages.

At that time, Mardi Gras was as segregated as the city itself, and the Zulu parade was a subtle form of protest – a way for working-class Black men to safely rib the upper-class white population, while bringing the community together. The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, which organized the Zulu parade, worked year-round, raising money for proper burial of its members. Even today, members of the group bring Christmas presents to children in need and fundraise for college tuition for the community’s high schoolers.

Each year on Fat Tuesday, parade-goers and organizers marched for miles through the streets of New Orleans in grass skirts, feathered hats, and wielding coconuts. They also painted their faces in bold strokes of black as a way to shield their identities, which was, at the time, a city law during Mardi Gras, meant to protect the identities of paraders regardless of race. Most Mardi Gras participants wore masks, but the Zulu members could not afford them. The choice of black face paint was no mistake. It was meant “to seize upon racist symbols and invert them as demonstrations of African American power,” historian Ari Kelman told PBS’ “American Experience.”

“That African Americans choose to wear blackface demystifies racist cultural symbols and norms, robbing those symbols of some of their sting,” Kelman said.

The use of blackface by some Zulu parade members is a subject of high tension. People began to question the practice during the civil rights movement, and today, some members like City Councilman Jay Banks insisted to CNN, though, that “our costumes are warrior-like, and they have nothing to do with the buffoonery when these idiots do blackface.”

For young Armstrong in 1909, the costumes and face paint alike symbolized a Black power he had not seen before. The parade meant a chance to see his own neighborhood, his own people, shine. The rest of the year, his neighborhood might be belittled by the rest of the city, a symbol of terrible neglect, segregation, poverty and crime, but during Mardi Gras, it was something to be proud of. According to Time magazine, Armstrong dreamed of one day leading that parade, and of reigning as the King of Zulu.

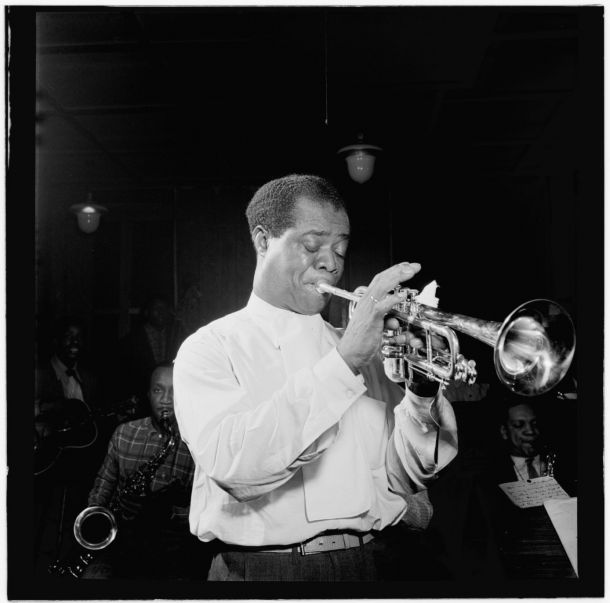

40 years after the first Zulu parade, that dream would finally come true. By then, Armstrong was a universal icon – a master trumpeter who had revitalized the world of jazz and made it his own. Armstrong’s unrivaled playing had ended the reign of big band jazz and made room for small bands to rise to the top. By 1949, he was travelling around the world to play his music but returned to his hometown for the honor of leading the parade.

That Tuesday in 1949, Armstrong set out on the 20-mile parade route, sitting atop a float with painted face and a cardboard crown balancing on his head. Armstrong’s wife, Lucille, worried about him getting so close to the crowd, afraid he might be trampled by well-meaning fans or get lost in the shuffle. According to Time magazine, she asked her husband how she could find him. To that he smiled and said, “Baby, just follow the crowd.” Armstrong claimed he could never get lost in the city that raised him.

But even as the city celebrated Armstrong, the enduring segregation in New Orleans was ever-present. Armstrong was still only allowed to stay at certain hotels, and relegated to parade through certain Black neighborhoods on the float. The rest of the world was shocked that this was how the city welcomed the jazz legend, but Louis focused instead on giving back to the neighborhoods of his youth. He served potato salad and beer to hungry parade-goers, filled the streets with his music, and single handedly stocked 2,000 coconuts (a Zulu tradition) to toss into the happy crowd.

In the end, a stampede of fans tried to take down Armstrong’s float, in an effort to get nearer to him. He was quickly whisked into a limo for safety – but he said he was never afraid or resentful. Armstrong played four concerts in New Orleans before he returned to touring and a life on the road.

After all, for Armstrong, no place was like home, and the Zulu parade gave the trumpeter a chance to give something back to the city he loved. “Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine,” he once said, “I look right into the heart of good old New Orleans. It has given me something to live for.”