In the late 1980s, a movement emerged in response to the lack of resources, communication and support provided to those with HIV and AIDS. Because the disease was initially labeled Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID), much of the activism surrounding AIDS focused on gay men, linking the illness to specific sexual behavior. In reality, the virus was not exclusive to the gay male community.

Women and intravenous drug users were initially excluded from the medical AIDS definition and therefore most clinical trials also excluded these populations. Although activists were able to successfully have HIV’s diagnostic definition updated in the 90s, many women found it challenging to advocate for themselves and others in relation to a disease that had been predominantly associated with men, both in terms of activism and resources available.

Among the women who were AIDS activists, Sharon M. Day helped to create the Indigenous Peoples Task Force (IPTF) in response to the lack of resources and attention provided to Indigenous communities. Here she shares her personal experience on the frontlines of the AIDS epidemic.

In 1985, my younger brother Mike called me up and said, “I need to fly to Chicago, can you take me to the airport?” He told me, “I have a friend who is dying and there is no one to be with him.”

On the way to the airport he said, “If I ever get ‘the big A,’ promise me you won’t let me die alone.” “I promise.”

Two years later, he called me at six in the morning and said, “It’s ‘the big A,’ sis.”

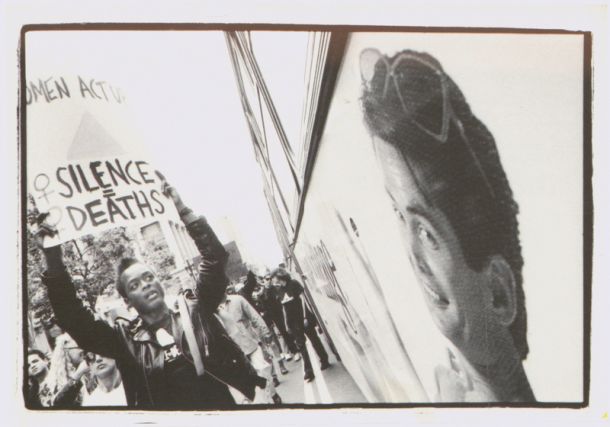

ACT UP Womens Action postcard, 1990. AIDS Collection, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

I cried all the way to my mother’s house and then tried to compose myself before I went to the door. In those days, AIDS was a death sentence. “We have to call Mike,” I told her.

She walked over to the phone on the wall, picked up the receiver and dialed his number. I couldn’t hear what he was telling her, but I could hear her: “Mhm, mhm.” Silence, then “I want you to come home where you will be with people who love you.”

That was the beginning. 1987. A woman I knew who was a nurse called me up: “I have AIDS, there are no services, what are you going to do?”

At the time, I was the Special Assistant Director for the Chemical Dependency Program Division at the Minnesota Department of Human Services. Since injecting IV drugs was one of the most efficient ways of transmission, it made sense for me to do something. So, I hired a young Native Nurse who was working on her master’s degree to write an HIV curriculum to educate Native Americans around the state. A few of us created a coalition and started to meet to determine what was happening. We fully expected someone to take up where we had started providing prevention, intervention and case management services for people in our community. That did not happen.

In 1987, we formed the Minnesota American Indian AIDS Task Force (MAIATF). We were losing people every day. After two years, I took a leave of absence from the state and became the first Executive Director of MAIATF.

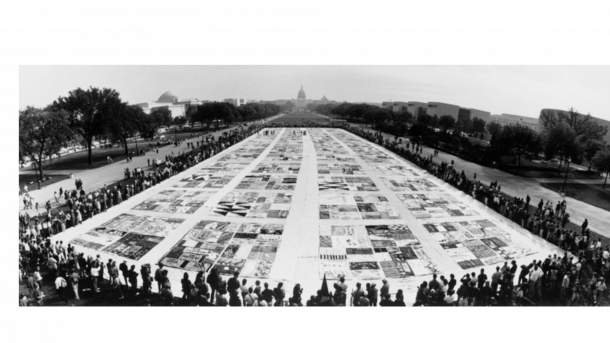

NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt on display, 1988. Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library via California Digital Library.

If the state of Minnesota was not doing enough for Native People living with AIDS and their family members, the federal government was doing even less. At the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, Georgia in 1987, a few of us delegates marched blocks carrying panels from the AIDS quilt. We were met a block away from the convention center by a SWAT team of police officers all dressed in black. There were 12 delegates, mostly lesbians with a couple of gay men. My friend, Keith Gann, was the first gay man living with AIDS to address a national convention.

Around 1988, the Surgeon General C. Everett Koop spoke at a conference in Minneapolis. I asked him, would he encourage the use of traditional medicines for Native Americans living with AIDS? He said he didn’t believe in “barefoot” medicines. In the meantime, we were losing so many people. When AZT and the drug cocktails became available to those living with AIDS, we lost people who were compliant with the dosage and usage. To this day, no one knows why in those early years of HAART therapy, Native Americans were still dying; some after being prescribed eight different cocktails.

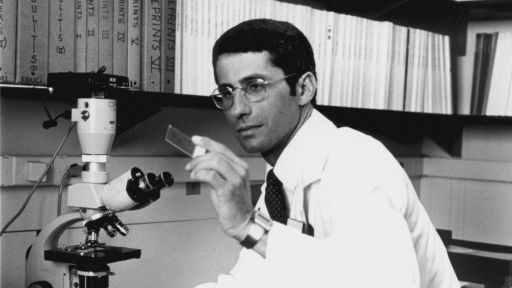

We knew who Dr. Fauci was at the time and we were grateful for his work, as well as our partners at the Centers for Disease Control and the Minnesota Department of Health. Sadly, much of the issues that were not being addressed became the focus of such activism with groups like ACT UP. These issues are still present today.

In Minnesota, we are dealing with an HIV outbreak spurred on by social justice issues like the many people who are unsheltered and living in encampments and the upsurge in Opioid usage. Native Americans are seven times more likely to die of an overdose than the white population. We are the state where George Floyd lived and died and all the calls for reform of the justice system and diversifying the organizations, foundations and governments have quietly gone by the wayside. We need ACT UP and so much more today.