Even in the 21st Century, if you went to Rebecca Nurse’s house, in what used to be Salem Village, and knock on the door, someone fascinating would open it.

I discovered this when I visited Salem in 2005, driving there to do some research for a university production of The Crucible. Salem is about an hour’s drive due northeast from Boston and in the late 17th Century, it was a bustling seaport known as Salem Town. To say that Salem still remembers its malefic past is an understatement. In addition to the Salem Witch Museum (great gift shop, by the way), there is the Salem Witch Village, the Salem Witch Wax Museum, and, in a truly breathtaking flight (literally) of fancy, Count Dracula’s Castle. To be fair, there are some historical landmarks there, including the village hall where some of the witch trials took place, but the real site of the events in The Crucible is in a town called Danvers, known until 1752 as Salem Village.

Danvers is about five miles away, across a small river, to the northwest. It is surrounded by small towns (called parishes then) that figure prominently in the play’s story, including Beverly, which was the home of Reverend John Hale, and Peabody, where the Proctor’s farm stood. At the very end of the 17th Century, when the witch trials took place, Salem Village encompassed a wide swath of neighboring farms and, given how hard travel was in those days, the village kept its distance from Salem Town. In fact, scholars claim that tensions between Salem Town and Salem Village—the village wanted more autonomy and tax exemption—was one of the many reasons for the accusations of witchcraft. Still, Salem Village petitioned for and received its own clergyman—and within only eight years, they went through four ministers. They finally confirmed, by 1692, Reverend Samuel Parris, whom, by all accounts, was not liked very much by anyone either. The site of Parris’s church is one of Danvers’ historical landmarks to this day. And right across the street is, still standing on its original property, the house of Rebecca and Francis Nurse.

When I drove up the rough path that leads to the house, it was bitterly cold, but there her house stood, solid among the scraggly trees and rough-hewn split-rail fences. I walked around the estate and noticed the replica of the Salem Meeting House that had been built, as my Chamber of Commerce brochure told me, for a PBS movie about the witch trials. A slightly gnarled older man opened the back door and asked me what I was doing there. Startled, I felt like Dorothy and her three friends when they got to Oz and that funny little man demanded, “Who rang that bell?” I explained to the gentleman that I was teaching The Crucible and came up to do some research. “Are you teaching it as fiction or history?” he inquired pointedly. Now, I felt like Rebecca Nurse herself, three centuries earlier, being asked an abstruse question that clearly had a very right answer and a very wrong one. But I had a feeling that I knew what the gentleman was after. “Oh, fiction, fiction,” I replied. “Good,” he beamed, as he opened the door for me to enter the vestibule, “because it’s not history.”

And therein lies the crux of the matter.

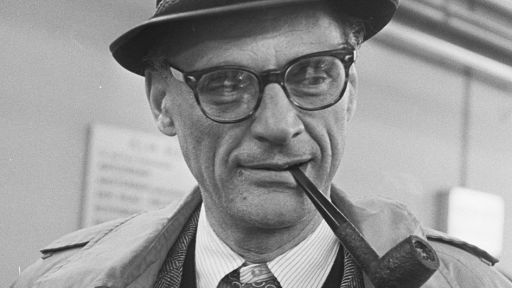

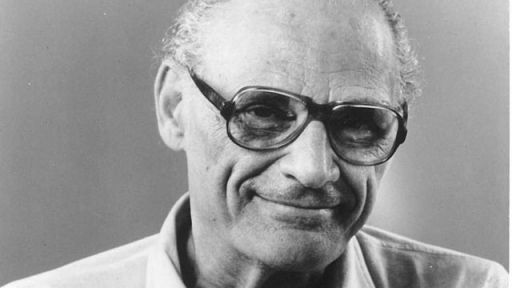

Arthur Miller makes no bones about his creative interpretation of the facts of the case. The first sentence of the published version of the play concerns “A Note on the Historical Accuracy of This Play”: “This play is not history in the sense in which the word is used by the academic historian.” Indeed, there is considerable variance between the actual events of the witch trials and the play, and they make for fascinating comparisons. The comparisons are not going to be used as a cudgel with which to beat Arthur Miller but, rather, as a way to get to a more resonant reading of the play.

The facts, recorded with the utmost brevity, are these: In the early part of January, 1692, the nine-year-old daughter of Reverend Parris, Betty, and her eleven-year-old cousin, Abigail Williams, exhibited bizarre and seemingly unprovoked behavior: seizures, trances, blasphemous screaming. Utterly bewildered, Parris called in a local doctor, who, unable to find any physical cause for their tortures, professed the girls to be under the spell of Satan. Parris soon led the villagers in various fasts and prayers for the girls’ souls and called in several other local clergymen, including Reverend John Hale. Within weeks, similar symptoms had affected eleven other girls and women of Salem Village, including two teenagers: Mercy Lewis and Mary Warren, the servant of a respected farmer in his 50s, John Proctor, and his third wife, Elizabeth.

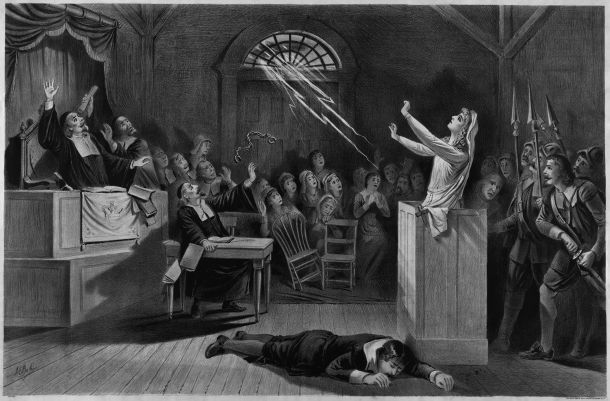

Through the exponentially frightening torments of these women, some clear details emerged: they were all being tormented by three local women who had the power of witchcraft: Tituba, a West Indian enslaved by Reverend Parris; Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne—middle-aged housewives who were not particularly beloved by the community. Two magistrates, Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, called the women in for examination. In a breach of judicial etiquette still shocking, the women were questioned in the presence of their accusers; the girls lapsed into the same bewitched pyrotechnics during the examination, further inflaming the situation. Tituba confessed to consorting with the devil and implicated the other two as witches; all three were moved to a Boston jail to await a further trial.

This did little to untangle the situation; within days, the bewitched girls named four more members of the community, including a fine upstanding woman, Rebecca Nurse, and a five-year-old girl named Dorcas Good. (Dorcas was eventually released after four months, but, accordingly to her father, was traumatized into imbecility for the rest of her life.) In March and April, the frenzy of accusation spread through the community like kerosene in a hayloft. Untold locals of Salem Village stepped forward to proclaim that they saw their neighbors flying through the air, or signing the book of Satan, or talking to animals, or wreaking subtle havoc on their property or livestock. Dozens more, including the Proctors, were brought in to be examined by local magistrates—almost always in the presence of the frenzied accusers—sometimes stripped and searched for “witchmarks,” and imprisoned. Amazingly, according to the custom of the time, the accused were billed for their “lodging” in jail.

One might well wonder why there was no trial of these individuals, let alone even a kangaroo court to try them. Sadly, and probably fatally for some, Salem was still under the jurisdiction of the British Crown and the Massachusetts Bay Colony had been negotiating a proper charter for months with the authorities in England. In other words, there was no trial, because there was no recognized government for a brief period in the spring of 1692—a period that corresponded exactly to the time of the witchcraft accusations. Finally, at the end of May, charter negotiations had progressed far enough that a “proper” court was convened by the Governor of the colony. Seven distinguished legal minds were appointed as justices, including (but not prominently) John Danforth.

The justices conducted themselves as best they knew how, but their methods weren’t simply shoddy by our standards, they were nearly certifiably insane. The bodies of the accused were searched for satanic disfigurements; they were asked to perform supernatural feats; they were brought into contact with their accusers to see if their very proximity induced bewitched behavior (surprise: it almost always did). Most controversially, the judges allowed for “spectral evidence” in the court; i.e., testimony from witnesses that they had seen the accused in ghost-like form tormenting cattle, or roaming around the neighborhood in the dark of night. This is why it is essential for civilized societies to have rules of evidence.

After two weeks of hearings, the jury brought down its sentence on June the second: a woman named Bridget Bishop was to be hanged as a witch on “Gallows Hill,” to the west of Salem Town. (Witches were always hanged, never burned, as their punishment.) Over the summer of 1692, the jury returned twenty-seven convictions of witchcraft; nineteen people were hanged; another five died while in prison, and one brave old man, named Giles Corey, was “pressed to death”—heavy stones placed on his body—while the authorities vainly tried to exact a confession from him. Eight women were convicted, but released, including Elizabeth Proctor, who was with child. Two of the accused women confessed to being witches and were reprieved—paradoxically, if you admitted to being a witch, you were freed. One of these women was Tituba, who was there at the beginning, nine months earlier; she was sold back into slavery. A year later, in 1693, authorities began to question the proceedings and there were many acts and deeds of contrition, shame, and official exoneration. As late as 1957, the Massachusetts General Court officially absolved one of the women of the crime of witchcraft; but, by then, the country was in the midst of another witch hunt.

These, then, are the facts (and, trust me, this was as brief as I could make them). The court records of the time are quite clear, with some exceptions. This is what happened. Yet, even now, three centuries later, we do not know why it happened.

Many theories abound. The result of tensions and conflicts between Salem Town and Salem Village; between disputative neighbors. The inflamed emotions of some bored prepubescent girls, locked in a quotidian existence of household drudgery. An epidemic of fungus in local bread, called “ergot,” which is a mild hallucinogen. The most recent book on the subject, published two years ago, makes a persuasive case that the witchcraft hysteria was the result of the extended King Philip’s War and King William’s War in which the British settlers to the north of Massachusetts were being slaughtered and scalped by tribal nations in relentless raids on their communities. Several of the accusing girls were refugees from settlements destroyed by the Wampanoag nation—perhaps they were suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome and fearful of being attacked again. Perhaps the judges in the witchcraft trials needed to displace their failure in protecting their citizens from the devastations of war, and so used the pitiful settlers of Salem Village as scapegoats.

Perhaps, perhaps. Having wearied the reader already with the accounts of the actual trials, I will not subject her or him to an extensive comparison of these events with those in the play—you are clever enough to figure those out for yourself. Arthur Miller traveled to Salem and did his research in the local archives and was inspired—for his plot—by a conspicuous gap, it seemed to him, in the court records when it came to Abigail Williams’s testimony against John Proctor. This opened the door to his own original thinking about the story; he arrived at the subtext through his own life and marriage and he nestled his story in the middle of his own strong feelings about the witch hunt of his own time during the McCarthy era and the House Committee for Un-American Activities.

Time has not been kind—nor should it be—to those “other men” of state administration whom Miller was attacking. But, I confess—there are many confessions in the world of The Crucible—upon research and reflection, to a certain sympathy for the justices in the Salem case. Why? They were simply stumbling in darkness. This was a pre-scientific society: Galileo had only been persecuted five decades earlier—much less time than between the HUAC hearings and now; Franklin was half-a-century away from flying his kite and discovering conductivity; the circulation of the blood was only a notion in the mind of Sir William Harvey. There were no videotapes or encyclopedias of witchcraft; indeed, there were only a handful of pamphlets and manuscripts on the subject—in England and the colonies put together—and they were woefully inadequate and contradictory. How could these men define witchcraft? Back then, there was no scientific proof that it didn’t exist, let alone that it did. I hesitate to say that these men, by all accounts decent and learned men, were making it up as they went along. The image that comes to me is that of Wile E. Coyote, or some Warner Bros cartoon figure, trying to cross some chasm and walk across it by drawing a bridge in front of him, inch by inch, in the hope that it will exist out of sheer belief and carry him across the abyss. The justices in the Salem case were duty-bound to protect their citizens—yes, perhaps they scapegoated some to save others—and they used whatever tools, iron-bound, rusted, and inadequate though they were, to forge some bounds of security.

That one might be moved to sympathize with the lot of the judges in the case is yet another tribute to Miller’s play. Every character is in a quest for certitude, whether it be moral certitude in the case of John Proctor, or evidentiary certitude, as in the case of Reverend Hale. We stumble in darkness, looking for whatever signpost or light we can find to take us to safety, to certainty. That Miller’s play allows for such deep, contradictory, and moving readings is a tribute to his artistry. That our society, now in its fifth century away from the Salem Witch Trials, still seems mired in misplaced jurisprudence, excessive finger-pointing and spurious assertions, and blustering and aggressive claims of moral certainty is sad condemnation of where we’ve found ourselves.