Olympic historian Michael Loynd details how swimming champion Charles Daniels “passed the torch” to Duke Kahanamoku, bringing the art of swimming to the world stage. Learn more about Charles Daniels in Loynd’s book, “The Watermen: The Birth of American Swimming and One Young Man’s Fight to Capture Olympic Gold,” which explores Daniels’ ascent from a lonely child with an obscure interest in swimming to an international icon who invented the modern freestyle stroke and allowed America to take its place as a global power at the Olympics.

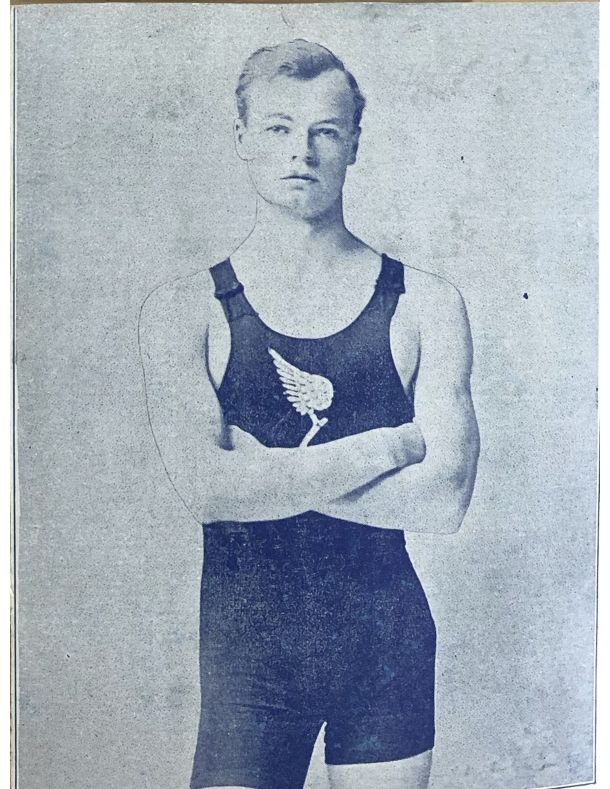

In January 1913, newspapers across the country broke the news that America’s two greatest watermen—the first, Charles Daniels, and his successor, Duke Kahanamoku—might finally agree to a match race. 27 year-old Daniels had been retired for over a year, but a recent visit to his old New York Athletic Club pool created quite the stir when he clocked a 100-yard swim in just fractions of a second off the world record. Only a year earlier, Daniels had retired at the top of his game, holding every American record from 25-yards to the mile. He willed the U.S. Olympic Swim Team into existence, created the freestyle stroke, popularized aquatics at a time when no one in America swam and claimed seven Olympic medals—a record that would remain until Mark Spitz beat it in 1972. When he retired the year before the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, the entire country begged him to reconsider. They believed without its great champion American swimming would return to being a laughingstock. The British Empire’s swimmers echoed that sentiment, preparing to reclaim their rightful throne.

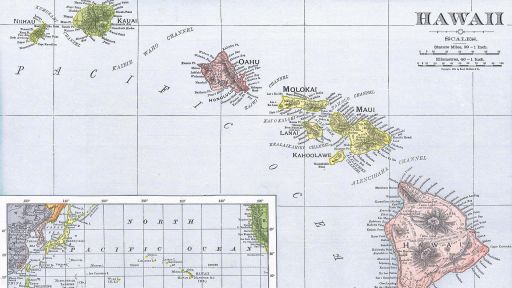

Until Daniels, the British Empire’s swimmers had dominated the sport for three-quarters of a century, ever since they had invented it. For almost a thousand years before, the art of swimming had been lost in Europe to the church’s oppressive moral decency laws that forbade any state of undress. Not until a deadly cholera epidemic broke across Europe in the early 1800s did England resurrect the ancient Roman custom of bath houses to promote better hygiene amongst the poor unwashed masses. Almost as soon as England built these bathing facilities, patrons began racing one another with the breaststroke—one of the few known strokes of the day. England quickly established rules, and the sport of competitive swimming was born. Later, when the advancement of city waterlines allowed them to build bath houses away from waterways and deeper into the inner-city, they began building larger tanks to accommodate swimming competitions. By 1869, England established the first and foremost governing body of swimming to sanction competitions, hold championships and verify and maintain all speed records. Participants also began experimenting with faster ways to swim.

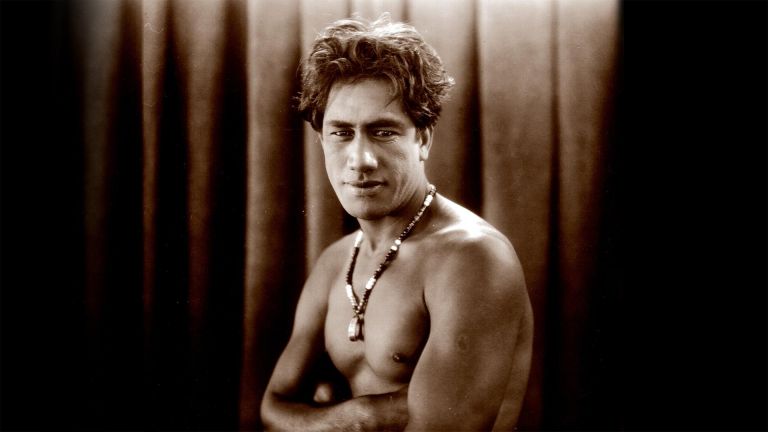

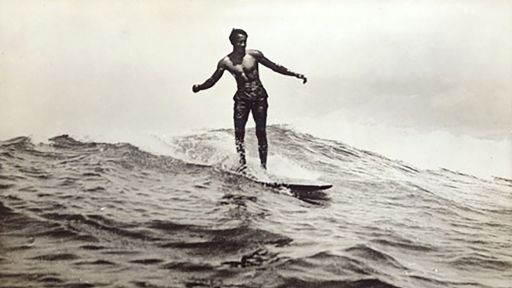

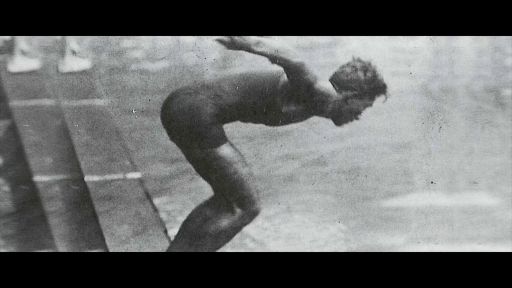

By the late 1890s, Australian swimmers of the British Empire began experimenting with the earliest version of the crawl stroke, derived from Pacific Islanders and similar to the stroke Duke Kahanamoku learned as a boy in his native Hawaii. By 1906, Charles Daniels perfected what we now know as the freestyle stroke with his six-beat kick, stunning the world when he defeated the seemingly unbeatable British Empire. Daniels spent the next five years dominating the sport and working tirelessly to popularize swimming in America, showing up at the openings of new indoor pools across the country to compete, teach and put on exhibitions as U.S. Swimming’s earliest ambassador. When he retired in 1911, he had groomed the next generation of American speed swimmers, but not until Duke Kahanamoku appeared on the scene five months before the 1912 Olympics was there a clear heir apparent.

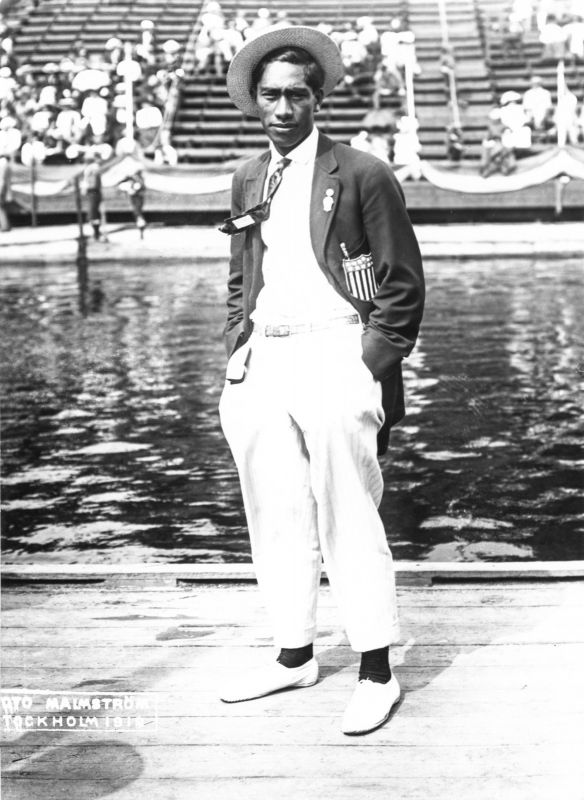

With the help of Penn’s George Kistler, the first college swimming coach in America, and Otto Wahle, Daniels’ former trainer and the inaugural U.S. Olympic swimming coach, Kahanamoku learned how to compete in swimming pools and perfect his wall turns and freestyle form. The country still clamored for Daniels to compete in 1912, but the retired champion felt if America was ever going to prove itself as a formidable swimming power—and not just the one-horse show as accused by the British—it needed to do so without him. Kahanamoku was the man they looked to. He would be pitted against one of Daniels’ greatest rivals, the Australian champion Cecil Healy, at the 1912 Olympics.

However, when the 100-meter gold medal race was called in Stockholm, the American team was nowhere to be found due to a scheduling confusion. Because of the respect Healy had for American swimming after being defeated by Daniels in 1906, he refused to swim the race until the Americans arrived to defend Daniels’ 100-meter Olympic title. Because of Healy’s honorable display of sportsmanship, Kahanamoku not only reclaimed Daniels’s title for America, but broke Daniels’ 100-meter record by 1/5 of a second. Healy took silver.

Kahanamoku returned to America a conquering hero. The torch had been passed, though not before the public demanded a match race between their two great watermen.

But Daniels demurred. Both men were cut from the same mold—humble and shy and had overcome much in life to achieve what so many thought impossible. Daniels was just thrilled to see U.S. Swimming in Kahanamoku’s great hands and graciously faded off into the sunset—something Kahanamoku later did with Johnny Weissmuller. And so the match race between the two never happened. But their legacies kicked off the greatest dynasty the modern Olympics would ever know, with the U.S. Swim Team now claiming more gold medals than the next eleven countries combined.