“I never knew of but one artist, and this is Tom Eakins, who could resist the temptation to see what they think ought to be rather than what is.” – Walt Whitman

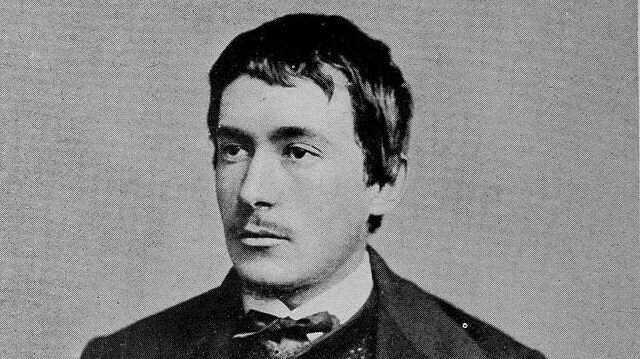

When Thomas Eakins died in 1916, he left behind a body of work unprecedented in American art for its depth, strength, perception, character, and commitment to realism. Yet during his life, Eakins sold less than thirty paintings. Rejected by the public and the art establishment of his day, it was only after his death that a new generation of scholars and critics recognized Eakins as one of America’s greatest painters.

Born in 1844, Thomas Eakins lived most of his life in his home city of Philadelphia. After graduating high school he attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He simultaneously took anatomy courses at Jefferson Medical College, in the hopes of creating more realistic pictures and gaining further insight into the human figure. In 1866 he left Philadelphia for Paris and later Spain, where he studied art and found the works of painters Diego Velásquez and Jusepe de Ribera. Along with Rembrant, these painters would be his greatest influences. A year later he returned to Philadelphia, never to go abroad again.

Throughout the 1870s Eakins painted the interior and exterior life of everyday America. He was concerned with the functioning of the physical world, as well as the inner lives of the people he painted. His paintings were both realistic and expressive. His attention to light, landscape, and the human form made Eakins stand far above his contemporaries. Among the most famous paintings of the time are his group portraits made at medical schools. Striking in their honesty and strict attention paid to the details of the human body, they shocked many in and out of the art world.

In the 1880s, Eakins’ interest in realism brought him in contact with the photographer Edward Muybridge. The two collaborated on photographing the movement of animals and humans. Though few painters took it seriously, Eakins believed the new photographic technology was a tool to better represent the physical world. Throughout much of the 1880s, Eakins brought these interests to students at the Pennsylvania Academy, encouraging them to study anatomy and work from live nude models. In 1886 his insistence on the use of nude models saw a great deal of criticism. Frustrated with the criticism, he eventually resigned.

Though he continued to teach at a number of different colleges, it wasn’t until long after his death that Eakins’ innovations in art education were recognized and adopted throughout the country. By the 1890s he had moved from his earlier outdoor works like “Max Schmitt in a Single Scull,” (1871), a perfectly rendered quiet picture of a rower on the Schuylkill River, to portraiture. In the many portraits completed over the last thirty years of his life, Eakins retained his passionate adherence to realist representation. Unlike most other portrait painters of the time, Eakins had little concern for flattering his subjects , and instead demanded from himself the most precise objective images. The results were thorough and telling portraits that seemed to carry with them the souls of their subjects.

During the final years of his life, Eakins began to receive a bit of the recognition he deserved. On June 25, 1916 he died in the Philadelphia home in which he was born. Against social demands for propriety and respectability, Eakins refused to compromise and painted his subjects as they really were, and not as they wished to be seen. His paintings reflected the passing of time, the awareness of mortality, and the nobility of everyday life. His courageous persistence in advocating his personal vision changed the nature of art education and provided future generations with a deeper view of the time in which he lived.