Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am is an artful and intimate meditation on the legendary Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning author that examines her life, her works and the powerful themes she has confronted throughout her literary career. From her childhood in the steel town of Lorain, Ohio, to ’70s-era book tours with Muhammad Ali, from the front lines with Angela Davis to her own riverfront writing room, Toni Morrison leads an assembly of her peers, critics and colleagues on an exploration of race, America, history and the human condition as seen through the prism of her own literature. Inspired to write because no one took a “little black girl” seriously, Morrison reflects on her lifelong deconstruction of the master narrative. Woven together with a rich collection of art, history, literature and personality, the film includes discussions about her many critically acclaimed works, including novels “Beloved,” “The Bluest Eye,” “Sula” and “Song of Solomon,” her role as an editor of iconic African American literature and her time teaching at Princeton University.

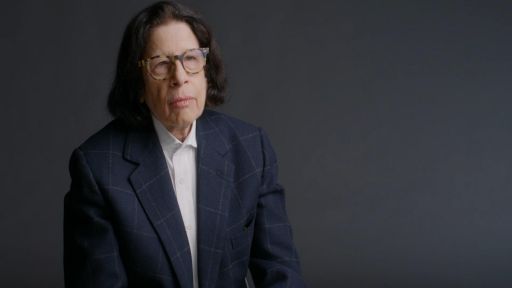

In addition to Morrison, the film features new interviews with Hilton Als, Angela Davis, Fran Lebowitz, Walter Mosley, Sonia Sanchez and Oprah Winfrey, who turned “Beloved” into a feature film. Using director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’ elegant portrait-style interviews, Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am includes original music by Kathryn Bostic, a specially created opening sequence by artist Mickalene Thomas and evocative works by other contemporary African American artists including Kara Walker, Rashid Johnson and Kerry James Marshall.

Photos: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders