By Harvey Kubernik c 2008 and c 2011

When Tapestry first revealed itself to an unsuspecting public, music critic Robert Hilburn, in a Los Angeles Times article published on April 25, 1971, stated that its themes were “Expressions of love, friendship, [and] home on such songs as ‘Where You Lead,’ ‘Home Again,’ and ‘So Far Away.’ As a writer, pianist, and vocalist Ms. King is a bright new record talent.”

In the April 29, 1971 issue of Rolling Stone, Jon Landau opined, “Carole King’s second album, Tapestry, has fulfilled the promise of her first and confirmed that she is one of the most creative figures in all of pop music. It is an album of surpassing personal intimacy and musical accomplishment and a work infused with a sense of artistic purpose. It is also easy to listen to and easy to enjoy. The simplicity of the singing, composition, and ultimate feeling achieved the kind of eloquence and beauty that I had forgotten rock is capable of. Conviction and commitment are the life blood of Tapestry and are precisely what make it so fine.”

Born Carole Klein, on February 9, 1941 or ’42, in Brooklyn, New York, King started learning piano at the age of four. She formed her first band, the vocal quartet the Co-sines, while a student at Madison High School, from which she graduated in 1958. A fan of the composing and production team of Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller (the duo behind remarkable records with the Robins, the Coasters, Elvis Presley, the Drifters, Ben E. King), King became a fixture at DJ Alan Freed’s Rock ‘n’ Roll shows, featuring the likes of Chuck Berry, Larry Williams, and the Everly Brothers.

While attending high school, she met budding songwriter Neil Sedaka, who went to Lincoln High. Later, she met Paul Simon at Queens College, as well as chemistry major/lyricist Gerry Goffin, with whom she forged a writing partnership and who would also become her future husband. Sedaka helped the Co-sines get an audition with Atlantic Records’ Ahmet Ertegun, and simultaneously Jerry Wexler gave her an office meeting to hear her material. King cut a couple of records under her given name: for the Alpine label “Oh Neil,” a response to Neil Sedaka’s own hit “Oh Carole,” and “Short Mort,” a 45 RPM on RCA Victor. Don Costa, then A&R at ABC-Paramount Records had King’s debut single, “The Right Girl,” released on the label in May 1958. Sedaka also introduced Carole King and Gerry Goffin to Don Kirshner, who helmed a publishing company, Aldon Music, with Al Nevins. King and Goffin subsequently worked with Nevins and Kirshner’s Aldon Music (in the Brill Building).

A decade of songwriting success followed, during which Goffin-King delivered a slew of memorable U.S. and U.K. hits: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” (Shirelles), “Some Kind of Wonderful” (Drifters), “Halfway to Paradise” (Tony Orlando), “Every Breath I Take” (Gene Pitney), “Point of No Return” (Gene McDaniels), “Take Good Care of My Baby” (Bobby Vee), “The Loco-Motion” (Little Eva), “Up on the Roof” (Drifters), “Go Away Little Girl” (Steve Lawrence), “Don’t Say Nothin’ (Bad About My Baby)” (Cookies), “One Fine Day” (Chiffons), and the proclamation “Hey, Girl” (Freddie Scott). King also collaborated with Howie Greenfield on “Crying in the Rain,” a cosmic record that Lou Adler produced for the Everly Brothers while they were on a tour in Omaha, Nebraska.

King had a charming hit single herself with “It Might as Well Rain Until September” on the Aldon Music-birthed Dimension label, which reached number 3 in the U.K. charts in 1962 and the top 30 in the U.S.

John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr were self-confessed Goffin and King fans, and George Harrison sang the lead vocal on the songwriting team’s “Chains.” The pair’s “Don’t Ever Change,” attempted first by the Beatles in their Decca Records audition recording, and initially waxed by the Cricketts, was discovered via bootleg and covered years later by Brinsley Schwarz and Byran Ferry. G&K’s “I’m Into Somethin’ Good” was cut by Herman’s Hermits with producer Mickie Most and their “Don’t Bring Me Down” produced by Tom Wilson charted for the Animals, and “Oh No Not My Baby” was initially placed with Maxine Brown, then subsequently re-done by both Manfred Mann and Rod Stewart.

“The work that Carole did with Gerry in that Brill Building-Aldon Music pressure cooker made an artist out of her.” says Kirk Silsbee, who a music historian, who writes about jazz and the arts from Los Angeles. “You can’t beat the discipline of working on demand and always looking over your shoulder to see if Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil or Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich are outdistancing you.”

“Then, there was the artistic standard set for all of them by the writing and production of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. They were always three jumps ahead of the younger songwriting teams, and they showed them the way. So Goffin-King got it from all sides. That was healthy competition, and that kind of boot camp is something you can’t put a price on. If you’re a real songwriter, you’ll only thrive in that kind of environment. That’s true of any artistic field where you’re forced to produce. You either rise to the occasion or you don’t. If you don’t, they get rid of you. When Don Kirshner sold the Aldon Music catalog to Screen Gems and Goffin-King started writing for the Monkees, the world changed,” says Silsbee.

But what differentiated Goffin and King from other songwriters of the era?

“At their best, the Goffin and King songs have a classic quality that outlive the time in which they were introduced. ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ is a question every woman has asked. Likewise, what woman hasn’t wanted to feel like a ‘Natural Woman?’ And who doesn’t need to get away and just be alone sometime, someplace like ‘Up on the Roof?’ Musically, those songs were also very well-constructed. They don’t require apology on any level. We know that demos were an important part of the Brill Building process. They were, for that time and place, what sheet music and song pluggers had been to the Tin Pan Alley songwriters. Some demos were so good that they became hits and needed no revision: ‘Locomotion’ by Little Eva and the Jimmy Jones hits, ‘Good Timin’’ and ‘Handy Man.’ Carole sang on the demos of some of her own songs and, of course, she had hits like ‘It Might as Well Rain Until September.’ I always thought that she made up for any lack of studied vocal quality with feeling. And, of course, her phrasing was good because she knew how her songs should be sung.”

“When she recorded ‘Natural Woman,’ I don’t recall anyone moaning that she wasn’t the singer that Aretha Franklin was. It was simply another shade of soul. Something about that plaintive, emotional voice on ‘Natural Woman’ is right-from-the-heart. No slick string charts sweetening the tune—just a solitary singer delivering an emotional statement. Carole took the intent of the song back to the root. Her piano playing, timing, and phrasing were very important to her vocals. There’s something that happens when pianists accompany themselves on a vocal. If they do it long enough, the hands, the voice, and the keyboard all become one instrument, and Carole had that. It’s funny—a few of the Goffin-King hits, like the Shirelles doing ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ and the Drifters on ‘Up on the Roof,’ were very pop-oriented, though they were cut by black groups. They were quite vanilla in contrast to what you might hear from some of the black artists of the day, like Don Gardner and Dee Dee Ford. Yet when Carole sang them ten years later, she added a degree of soul that hadn’t been there before to what we knew of those songs. The Shirelles sang ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ like girls. Carole sang it as a woman. A&M Records, where Tapestry was recorded, was a tremendously creative atmosphere, where it seemed like anything was possible. I’ve been told by people who worked there that there was an esprit de corps because that company was headed by a working musician. Then, there was the cachet of the A&M property, which had been Charlie Chaplin’s studio. Along with that went the lore about ghosts on the lot,” says Silsbee.

In the mid-’60s she, Goffin, and entertainment music columnist and writer Al Aronowitz founded their own short-lived New Jersey-based record label, Tomorrow Records, briefly distributed by Atco Records. Charles Larkey, the bassist for the Tomorrow group the Myddle Class, eventually became King’s second husband after her marriage to Goffin dissolved. Joel O’Brien, Myddle Class drummer, would later contribute significantly to King’s Tapestry.

The Goffin and King songwriting team formally ended in 1968, after their divorce, as Carole King began to pursue a solo recording career again.

By late 1970, the rock music scene was going through a sea change. The glory days of worshiping bands such as Love, Buffalo Springfield, The Doors were fading into a narcotic distance. The deaths of Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin (Jim Morrison’s was yet to come), the ongoing horror of Vietnam, and the break up of The Beatles all contributed to a subtle but clear change that made the audience desire a different relationship with the music. It was an intimate one, involving one-on-one rapport with the message, and the artist and the singer-songwriter delivered that message. Carole King was one this new genre’s thoroughbreds, a veteran of the late-50’s and early ‘60s immortal Brill Building scene, and an artist with an immaculate pedigree. After writing hits for The Byrds, Dusty Springfield, Aretha Franklin and others, by 1968 she had become a fixture in this new music community.

The FM radio vision of DJ’s Tom Donohue in San Francisco on KMPX and KSAN, and earlier Dave Diamond in Los Angeles on at KBLA-AM, free form, “underground” was veering to emerging singer/songwriters. The highly influential B. Mitchel Reed on KMET-FM in L.A., who was broadcasting demos of pre-CSN Crosby/Stills (as The Frozen Noses) in 1968, had been business partners with Lou Adler and Herb Alpert in the late ‘50s and very early ‘60s. Reed, a.k.a. BMR, a significant tastemaker, touted the King-defined City L.P., then the Writer album, and the legacy—even then—of Carole King. BMR alerted the music community in Southern California that “something heavy and really cool” was being cooked up at A&M Records on La Brea and Sunset. Only a couple of miles from where he and King both resided in Laurel Canyon, BMR picked his own tunes, informed the station’s play list, and continuously programmed whole sides of choice albums. He also programmed selections from other Ode solo LP’s from Peggy Lipton and Merry Clayton, two of the most interesting chicks in L.A. at the time.

“I like the fact that Lou Adler was a former partner with Herb Alpert and DJ B. Mitchel Reed,” says Kirl Silsbee. “BMR was the most musically knowledgeable of all of the broadcasters on the AM band in L.A. in the ’60s. I say that because if you listened to what he said and what he played, you learned about music and you gained a degree of taste. He introduced a lot of records—going back to the pre-Beatle ‘Color Radio’ days on KFWB: Jan and Dean’s ‘Surf City,’ ‘Poor Side of Town’ by Johnny Rivers, that Lou produced and co-wrote. And those are damn good records. Then there’s Lou’s Mamas and Papas chapter and the Monterey International Pop Festival, both of which Mitch was a cheerleader for. Somebody might find something nefarious in Mitch’s professional endorsement of these things that had Lou’s name on, but they were all quality endeavors. Mitch consistently introduced and endorsed a lot of the Laurel Canyon music by the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Love, and Doors. He subsequently did a lot to mid-wife the music of CSN&Y, James Taylor and Carole King. Mitch introduced Tapestry on KMET FM.”

City’s gorgeous “Now That Everything’s Been Said” vinyl album had planted the seeds for the future Tapestry sound to be discovered. A rhythm section of King and Danny Kortchmar really work well together with Kortchmar doubling a lot of her piano lines, a la “I Feel The Earth Move” that kicks off Tapestry. Charles Larkey is a fine bass player with a bit of funky edge to him. Toni Stern and Gerry Goffin had co-writes next to King’s self-penned efforts. The City was a group and the resulting album was “a Carole King vehicle,” but Carole could lose herself in a band identity and not be viewed as “Carole King’s new thing.” Adler was producing the movie “Brewster McCloud” and could not be the producer on King’s solo debut disc, Writer.

Danny Kortchmar was always a fan of Lou Adler’s studio acumen. “I thought Lou was the coolest cat there was…great laid-back attitude in the studio, always got across what he wanted to hear with minimal speech, had already made history, had the foxiest chicks, the best taste. I was in awe,” he says. “After I started doing more and more sessions for different producers it was re-affirmed for me how great he was.”

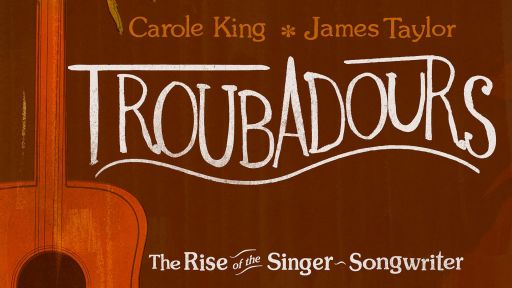

“People at the time needed a personal relationship with their artist, thus the ‘singer/songwriter’ genre was born, and Carole King proved to be one of its prime exponents,” states Matthew Greenwald, author of GO Where You Wanna Go, an oral history of The Mamas & The Papas. “The audience was over-amped, over electrified. This music was for people who didn’t understand the MC5…nor did they care to. James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, CSN&Y, Laura Nyro and Carole were the new avatars. People were needing to identify not so much with the band—Stones, Beatles, Beach Boys.” Instead, says Geenwald, people wanted a personal connection with the artist. “I’m going to have a relationship with Laura Nyro, Cat Stevens, James Taylor, Carole King and this newcomer Elton John. Something where people needed to step down from mass adulation, group hard-on stuff, a very much one-on-one experience of songwriting.”

Released in late-March 1971, Tapestry struck a universal chord at an opportune time in pop and rock music history—the intersection of folk-rock’s introspection and a socially conscious romanticism in a planet-gone-wild. Just prior to Tapestry coming out was the deregulation of the FM bandwidth, which resulted in a mini-explosion of so-called new “progressive” or “underground” or “free-form” radio stations eager to spotlight their own artists and playlists separate from the mainstream Top 40. In April of that year, King’s close pal James Taylor—who played on five Tapestry tracks – released “You’ve Got a Friend” as the first single from his new album, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon.

Carole King met James Taylor in New York at a Flying Machine gig and the two songwriters became close friends. Taylor encouraged King to pursue a solo career. 1970’s Writer emerged and then in 1971, King released Tapestry, which stayed on the charts for over six years and became the era’s best-selling album. A calm, reflective undertaking, Tapestry scored a pair of hit singles: “So Far Away” and the chart-topping “It’s Too Late,” the flip side of which, “I Feel the Earth Move,” garnered major airplay as well.

Matthew Greenwald believes the songs resonated deeply, in part, because they coupled strong sexuality with powerful emotion:

“‘I Feel The Earth Move’ is probably the most sexually aggressive song on the Tapestry album. It was a brave way to open this document, which is followed by a dominant flavor of ‘mellow confessionality.’ It was neatly book-ended at the end of the album by the updated ‘You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman,’ a similar sexual statement, but an emotional flipside. The neat symmetry between Carole and Danny Kootch’s unison piano/guitar lines on ‘It’s Too Late’ give the instrumental passages cohesion rarely found on such a ‘simple’ pop record. The listener is instructed to check out ‘It’s Too Late’ and ‘I Feel The Earth Move’ to fully experience this example of simple, yet ingenious arrangement design,” requests Greenwald. “This track burns with a low-key intensity that is absolutely haunting. And who knows, some of the instrumental feel of this track could have also influenced The Doors (‘Riders On The Storm’) or Traffic (‘Low Spark of High Heel Boys’).

“I don’t remember doubling too many parts, but if I did it was probably Lou’s idea,” recalls guitarist Kortchmar. “He was using all kinds of studio stunts I had no clue about at the time.”

Much of the album’s success derived from a new song-writing partnership, according to Greenwald.

“Carole found her complement in lyricist Toni Stern. Toni, who’d grown up on the Sunset Strip (where her mother managed a nightclub) was a striking, willowy bohemian. She wrote irony-tinged lyrics that reflected the slightly battle-hardened insouciance of the new hip, single woman. Carol and Toni played off each other. During interviews for my book, Toni told me that there was a ‘practicality in Carole that was comforting. I would hand her a whole lyric, neatly written out, and she would sit down and we’d have a song within hours…Working with her made me feel validated, like I wasn’t a wild child…I’m sure there was a California quality in me that appealed to Carole. She was moving from a familial, middle-class lifestyle to Laurel Canyon, where she started to let her hair down, literally and figuratively. We worked off our contrasts.’”

“But they would strike gold with Tapestry’s biggest hit, ‘It’s Too Late,’ whose lyric Toni, who usually agonized over lyrics, wrote ‘very fast, in a day.’ The song, with its almost ominously moody-turning-bouncily hosanna-like melody, describes a young woman’s realization that a romance she’d secretly banked on is over. On the surface, she’s shrugging and cool, but the insistent internal rhymes (‘inside,’ ‘died,’ ‘hide’), atop Carole’s own insistent melody, trumpet her hidden emotion.”

At the 14th annual Grammy Awards ceremonies in March 1972, Carole King became the first woman to win the “grand slam”—Record Of the Year (“It’s Too Late”), Album of the Year, and Best Female Pop Vocal (both for Tapestry), and Song of the Year (James Taylor’s version of “You’ve Got A Friend,” for which he won Best Male Pop Vocal).

About her Grammy winning composition “You’ve Got A Friend,” King revealed the evolution of the song to Adler in their taped 1972 A&M studio encounter, and how it landed inside Tapestry:

“Once I got to the stage of recording, I have feelings of wondering about whether it’s going to make it or not for a time, but the big questions about, you know, whether it’s going to make it or will people like it, all the big insecurities really happen when I’m writing the song. Once the song is being written and once it’s finished and I play it for you, and a few people whose opinions I respect, I begin to get a feeling. Sometimes, I already have the right feelings. Sometimes I don’t know. I didn’t write it with James or anybody really specifically in mind. But when James heard it he really liked it and wanted to record it. At that point when I actually saw James hear it, I watched James hear the song, and his reaction to it. It then became special to me because of him, you know, and the relationship to him. And it is very meaningful in that way but at the time that I wrote it. Again, I almost didn’t write it. When I write my own lyrics, I’m conscious of trying to polish it off, but all the inspiration…really comes from somewhere else. That was because his album Sweet Baby James was recorded the month before Tapestry was recorded, I think, or even possibly simultaneously. Parts of it were simultaneous. And it was like Sweet Baby James flowed over to Tapestry and it was like one continuous album in my head, you know. We were all just sitting around playing together, and some of them were his songs and some of them were mine.”

But why did King decide on Tapestry as the album title?

“It is typical of the magic that seems to surround that album, a magic for which I feel no personal responsibility, but just sort of happened, that I had started a needlepoint tapestry, I don’t know, a few months before we did the album, and I happened to write a song called ‘Tapestry,’ not even connecting, you know, the two up in my mind. I was just thinking about some other kind of tapestry, the kind that hangs and is all woven, or something, and I wrote that song. And, you being the sharp fellow you are, (giggles), put the two together and came up with an excellent title, a whole concept for the album.”

Darrow, a musician and friend of King’s, set the blueprint for the emerging Southern California country rock sound. Darrow has been a true SoCal musical insider for over 40 years. He attended the wedding of Carole King to Charles Larkey at their Laurel Canyon home. He recalls his first impressions of King performing Tapestry:

“I went to the Troubadour when Tapestry was released. I saw the early show. It was crowded and almost all the people in the room were women, mostly high school and college age. Almost all of them were with their mothers. I knew Carole King because she played on the ‘Sweet Baby James’ album. James’ album changed the entire visibility… t the Troubadour she just played by herself and was really good. One of the things that most people don’t understand is that she is a consummate songwriter. She knows form. As a person who played piano for songwriting demos, she had to play the essential song and play everything right down the middle. She was not playing solos; she was playing the song. Consequently, as a songwriter and a person playing piano on demos, her great ability was to center in on the song. That ability informed King’s shows, Darrow says. “Carole King’s Troubadour shows had an intimacy about them and everyone in the place felt she was singing to them. Most of the audience were women. 85-90 per cent of them were females but there were certainly some men around. But she wasn’t drawing men like Joni Mitchell and Linda Ronstadt. The climate wasn’t right for her Writer album when it was first released. Sweet Baby James opened the door for Tapestry. All of a sudden it was OK to be a singer/songwriter. That certainly opened the door for me as a solo artist,” he says.

Tapestry engineer, Hank Cicalo, remembers, “On Tapestry Lou and I did quite a few things. There was a thing about the middle of Carole’s voice where it’s almost warmth with a little edge. I always wanted to capture that. I thought her piano playing was great, she would sing, and she was such a writer and performer, she knew when to lay out and when to hit it. So that was always great. Then, when her vocals came when you mixed them, the spaces were always in the right places. Everything was supporting her voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was.

“The studio had a Howard Holzer special made console. His board you could really punch it. The only thing I had to worry about was tape there was no noise reduction in those days. Everything was supporting that voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was. No matter what happened in that room, it had to support it. You got to remember whole period everything was moving from two track tapes. I met Carole when she wrote songs for the Monkees, whom I did four or five albums with. The writer becoming the recording artist or star seemed to be a natural path for people performing as side people. And then they made an album suddenly becoming a star or an artist or performer. And see them grow, but we were all growing the producers, the record companies. The progression was natural.”

Harvey Kubernik is a Los Angeles native and a Southern California resident. Kubernik has been an active music journalist since 1972, a record producer since 1979, and a former West Coast Director of A&R for MCA Records. Kubernik wrote the liner notes for 2008’s Sony/BMG deluxe edition of Carole King’s Tapestry album. Harvey Kubernik’s latest book (among others), Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon, was published in October 2009 by Sterling Publishing. As part of the KubRo Group, you can learn more about his work at their Web site, davidcarrmusic.com.