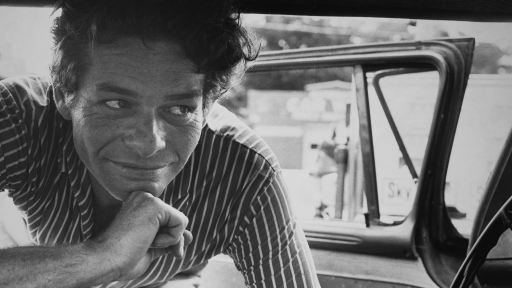

People worldwide have seen the Disney animated classic Bambi and been deeply moved by it, but few can tell you the name of the artist behind the film. Even fewer are aware of this pioneering artist’s impact on American art and popular culture. Until his death at the age of 106, Tyrus Wong (1910-2016) was America’s oldest living Chinese American artist and one of the last remaining artists from the golden age of Disney animation. The quiet beauty of his Eastern-influenced paintings caught the eye of Walt Disney, who made Wong the inspirational sketch artist for Bambi. Filmmaker Pamela Tom (A Tribute to Sir Sidney Poitier, Two Lies ) corrects a historical wrong by spotlighting this seminal, but heretofore under-credited, figure in American Masters: Tyrus, premiering nationwide Friday, September 8 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) in honor of the 75th anniversary of Bambi (August 1942). After the film, in a new, exclusive interview, filmmakers/artists Robert Kondo and Dice Tsutsumi discuss how Wong influenced them and share an excerpt from their Oscar-nominated animated short The Dam Keeper (2014). This segment and the documentary will be available to stream the following day via pbs.org/americanmasters and PBS OTT apps.

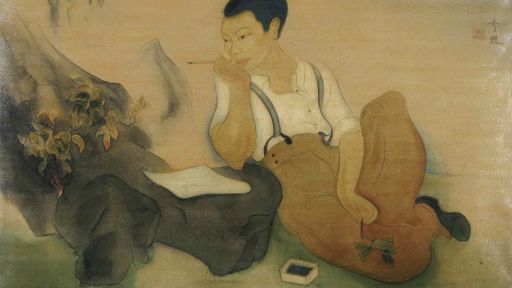

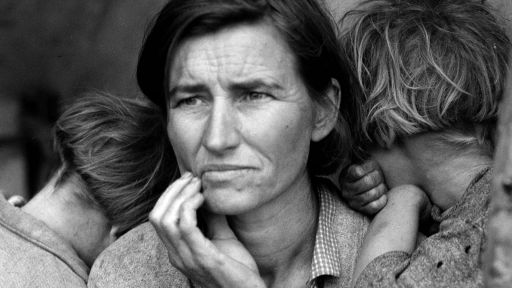

Born in Canton (now Guangzhou), China, right before the fall of the Chinese Empire, Wong and his father immigrated to America in 1919, never to see their family again. American Masters: Tyrus shows how he overcame a life of poverty and racism to become a celebrated painter who once exhibited with Picasso and Matisse, a Hollywood sketch artist, and ‘Disney Legend.’ Previously unseen art and interviews with Wong, movie clips and archival footage illustrate how his unique style – melding Chinese calligraphic and landscape influences with contemporary Western art – is found in everything from Disney animation (Bambi) and live-action Hollywood studio films (Rebel Without a Cause, The Wild Bunch, Sands of Iwo Jima, April in Paris) to Hallmark Christmas cards, kites and hand-painted California dinnerware to fine art and Depression-era WPA paintings. The film also features new interviews with his daughters and fellow artists/designers, including his Disney co-worker and friend Milton Quon, Andreas Deja (The Little Mermaid), Eric Goldberg (Aladdin) and Paul Felix (Lilo & Stitch), and curators and historians of Wong’s work.

“Tyrus Wong’s story is a prime example of one of the many gaping holes in our society’s narrative on art, cinema, and Western history,” said Pamela Tom. “By telling his story, I wanted to shine light on one of America’s unsung heroes, and raise awareness of the vital contributions he’s made to American culture.”

“When I met Tyrus, I knew very little about his astounding work, which I then saw displayed prominently at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco,” said Michael Kantor, American Masters series executive producer. “This beautifully realized film is a reminder that there are many American Masters who are not immediately recognizable, but when you learn about their stories, you’ll never forget them.”

Launched in 1986, American Masters has earned 28 Emmy Awards — including 10 for Outstanding Non-Fiction Series and five for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special — 12 Peabodys, an Oscar, three Grammys, two Producers Guild Awards and many other honors. The series’ 31st season on PBS features new documentaries about filmmaker Richard Linklater (September 1), author Edgar Allan Poe (October 30) and entertainer Bob Hope (December 29). To further explore the lives and works of masters past and present, the American Masters website (http://pbs.org/americanmasters) offers streaming video of select films, outtakes, filmmaker interviews, the American Masters Podcast, educational resources and In Their Own Words: The American Masters Digital Archive: previously unreleased interviews of luminaries discussing America’s most enduring artistic and cultural giants. The series is a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET and also seen on the WORLD channel.

American Masters: Tyrus is a production of New Moon Pictures, Apricot Films, Lux Mundi Productions, and Stone Circle Pictures in association with the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC’s American Masters for WNET. Pamela Tom is writer and director. Pamela Tom, Gwen Wynne and Tamara Khalaf are producers. Linda Barry is co-producer. Don Hahn, Robert Louie, David W. Louie and Buck Gee are executive producers. Michael Kantor is American Masters series executive producer.

Major support for American Masters and Tyrus is provided by AARP. Additional support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Rosalind P. Walter, Ellen and James S. Marcus, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, Vital Projects Fund, Judith and Burton Resnick, Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, The Blanche & Irving Laurie Foundation, and public television viewers. Additional support for Tyrus is provided in part by The Louie Family Foundation, The Walt Disney Company Foundation, Buck Gee & Mary Hackenbracht, the National Endowment for the Arts, County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, Bill Yee, East West Bank, and Women in Film.