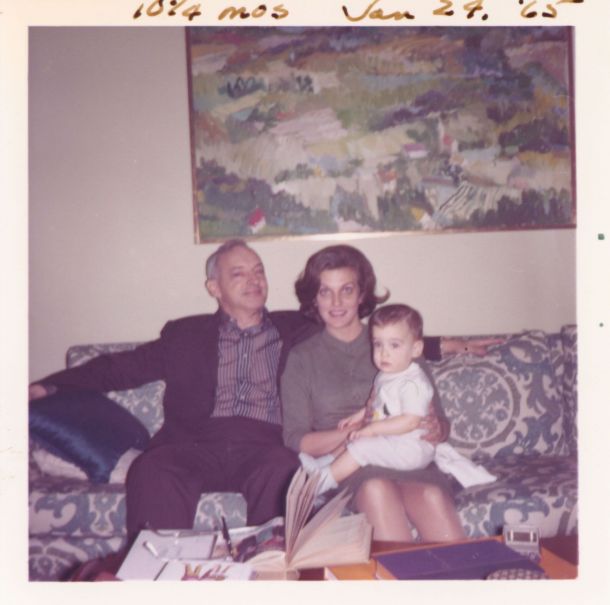

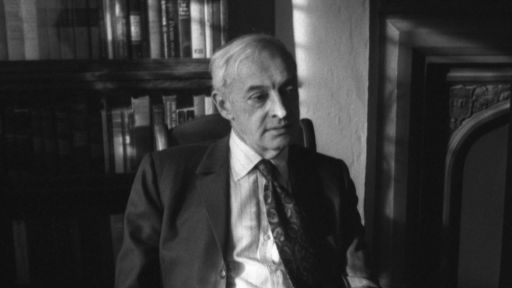

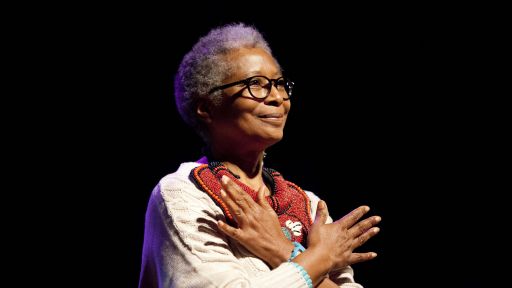

“My fictional life in a Bellow novel put me in the public domain,” wrote Saul Bellow’s ex-wife Susan in “Mugging and the Muse,” an unpublished work quoted in Zachary Leader’s biography of the novelist.

Susan continues, “Not one of the outrageous questions over the years, however, asked about the dark heart of the matter. How does the prize winner’s young and vulnerable son feel when asked in school if his mother is really so awful? Or when told by a buddy, who had the word from his mother, ‘Don’t read it. Your father did a number on your mom.’” 1

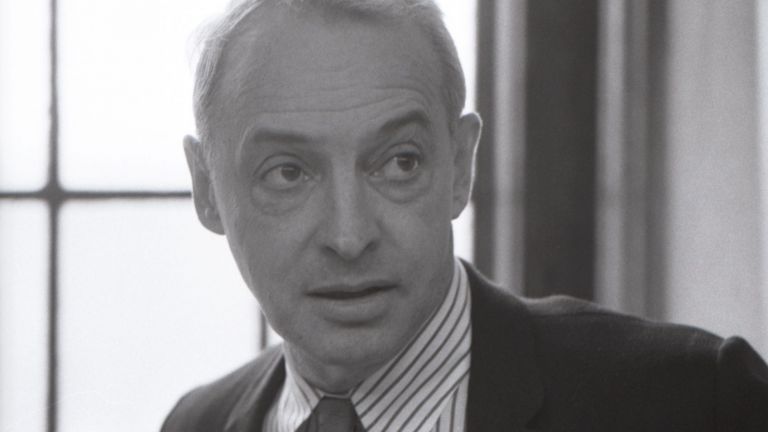

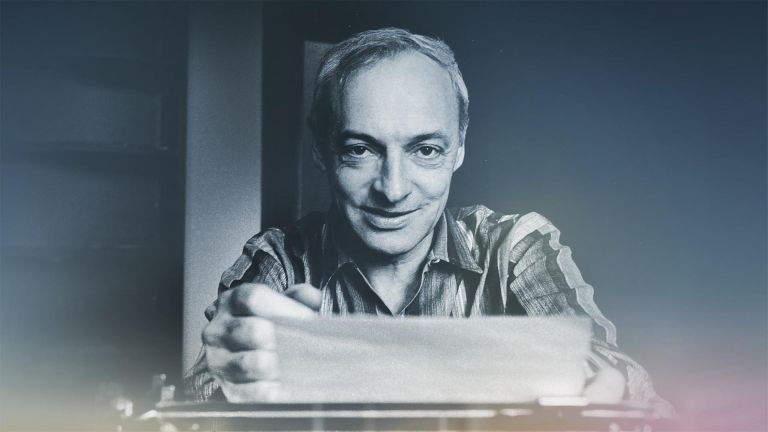

Saul Bellow hurt people with his writing. He meant to do so.

I write these sentences as someone who loves Bellow’s writing, especially “The Adventures of Augie March” and Bellow’s descriptions of Chicago and its people. Bellow’s Chicago in “Augie March” is diverse, vivid, teeming, passionately in motion. It’s crowded. It’s hopeful. It’s democratic. Here’s Bellow’s evocation of public college, which Augie and Simon start after the Great Depression upends their employment:

“Considering how much world there was to catch up with—Asurbanipal, Euclid, Alaric, Metternich, Madison, Blackhawk—if you didn’t devote your whole life to it, how were you ever going to do it? And the students were children of immigrants from all parts, coming up from Hell’s Kitchen, Little Sicily, the Black Belt, the mass of Polonia, the Jewish streets of Humboldt Park, put through the coarse sifters of curriculum, and also bringing wisdom of their own. They filled the factory-length corridors and giant classrooms with every human character and germ, to undergo consolidation and become, the idea was, American. In the mixture there was beauty—a good proportion—and pimple-insolence, and parricide faces, gum-chew innocence, labor fodder. . . . ”

As a professor in Chicago, I love teaching “children of immigrants from all parts” of that city, who even today enter class “bringing wisdom of their own.”

Bellow describes college using a list, an important formal technique. Bellow lists, and there are many, equalize and flatten what snobbery, nationalism, class division, racism and xenophobia would separate and stratify. High learning leans on street smarts, “pimple-insolence” matters at least as much as beauty. A Bellow list is democratic, jumbled, wonderful.

But readers should consider that Bellow aimed some novels directly at real people’s lives, intending and accomplishing hurt.

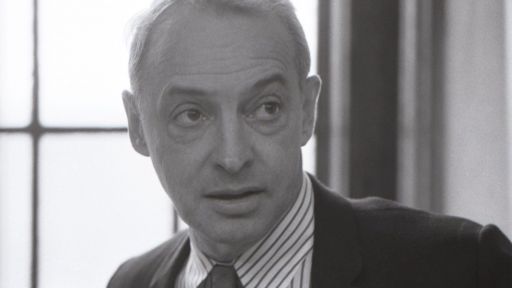

Writing in Slate in 2000, Brent Staples, a former graduate student at the University of Chicago, where Bellow taught, says he “learned to write by comparing Bellow’s novels to the people and circumstances he drew on when writing them. . . . Nor was I pleased with the way he portrayed his Black characters. And oh, by the way, yes, I am Black.” Bellow failed profoundly with Black characters, which are hollows webbed in stereotype.

And although there are delightful exceptions, such as hilarious, Machiavellian, worrying, multilayered Grandma Lausch in “The Adventures of Augie March,” Bellow’s female characters can be vacuous, especially if attractive. I suspect it’s no accident Grandma Lausch is past menopause. It seems much more difficult for Bellow to imagine humanity in a female who is a potential or former lover. When they are ex-wives in disguise, Bellow characters read as machines bent on ex-husband ruin.

Leader observes that Bellow came to see novels as weapons:

“In some novels and stories, people he knew, including friends and relations, were not only bound to see themselves depicted but they were meant to do so. ‘By the time I’m through with him,’ [Bellow] is reported to have said of the model for Valentine Gersbach in “Herzog” (1964), ‘he’ll be laughed right out of the literature business.’ ‘I’ll get you,’ he threatened his third wife Susan, before he ‘loused her up’ as the shrewish Denise in ‘Humboldt’s Gift.'”

Glaring through these quotes is Saul Bellow’s awareness of his novels’ unusual social power. At times, in my opinion, he betrayed his art.

The complexities of the sexism in “More Die of Heartbreak” and other novels have troubled me for decades.

In “More Die of Heartbreak,” the narrator nephew sees his Uncle Benn’s female lovers as interrupting his own (more valuable) intellectual bond with Benn. Characters in in this novel include Holocaust survivors. Bellow is well aware of the erasure of Jews as human beings that led to the Holocaust. Yet he wrote novels that deny women humanity, that question their intellectual capacity. He knew better.

Neither does Bellow suggest women have depth of thought in “Humboldt’s Gift.” “As a rule her own reflections satisfied her perfectly and she used my conversation as a background to think her own thoughts,” says Charles Citrine of his girlfriend Renata, a stand-in for Bellow’s real-life long-term mistress Maggie Staats, according to Leader.

“These thoughts, so far as I could tell, had to do with her desire to become Mrs. Charles Citrine, the wife of a Pulitzer chevalier. I therefore turned the tables on her and used her thoughts as a background for my thoughts.”

When Margotte tries to discuss Hannah Arendt’s work, in “Mr. Sammler’s Planet,” Sammler remembers his friend who “knew how to make Margotte shut up.”

Bellow’s wives were smart women, says Leader. Intelligent females sometimes appear in his fiction, such as Citrine’s ex-wife, Denise. But smart female Bellow characters usually propel inexorably toward ex-husband torment. Denise uses her smarts to sue Citrine. As “Herzog” opens, Madeline wrecks her husband’s academic career before divorcing him. These distorted ex-wife characters have counterparts in the real world. Any smart reader can figure out who they are.

Bellow was hardly the only mid-to-late 20th century writer to draw a sheer veil over real people as characters in his writing.

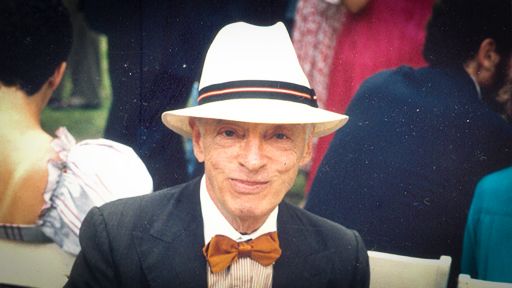

Mary McCarthy did it. So did Truman Capote in “La Côte Basque, 1965,” which cost him his New York social life and may have prompted the death of socialite Ann Woodward.2

A temptation-to-the-real conquered U.S. media culture starting in the 1990s, from “Cops” and reality TV to the rise of the memoir to the heyday of the true-crime genre (the modern version of which Capote invented in 1966 with “In Cold Blood”) to “The Crown.” Reality TV is famously cheap to produce. It makes money. The attraction is akin to gossip; it’s gratifying to watch proud people fall. None of this is at all new. But it’s newly pervasive.

Mediated reality, whether reality TV or a roman à clef,3 isn’t real, however. Reality shows steer towards conflict. “Cops,” one of the first of that genre, never showed the dull waiting that makes up much police-officer life; editing out the boring parts made crime appear more frequent. Memory studies imply serious problems with the whole memoir genre. And does anyone believe representations in “The Crown” rise above distortion?

Whether using real people as the basis for characters does harm, however, is the question that consumes me. The anguish of our 21st century “reality” moment may be something we learn to regret. But the costs of the savaging 20th century roman à clef are clear.

I will read Bellow for the wisdom and elegy, the perfect gesture, the Yiddish-inflected speech, the lost Chicago I never saw but miss because Bellow made it real. But I will read critically, with sorrow at Bellow’s inability to perceive whole portions of humanity, including many people he once claimed to love—he who sometimes saw Chicago so well.

1The Life of Saul Bellow: Volume One, To Fame and Fortune, 1915-1964 [Vintage, 2015], pp. 3-4

2 Editor’s Note: You can read “La Côte Basque, 1965,” here. This article would eventually become Truman Capote’s posthumous novel, “Answered Prayers.”

3 Editor’s Note: Roman à clef is a novel which presents real people or events as fiction, often using invented names.