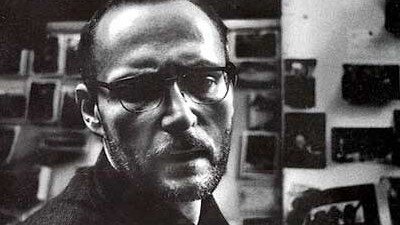

The war in the South Pacific, a country doctor in Colorado, victims of industrial pollution in a Japanese village — all of these were captured in unforgettable photographs by the legendary W. Eugene Smith. No matter where, what, or whom he was shooting, Smith drove himself relentlessly to create evocative portraits that revealed the essence of his subjects in a way that touched the emotions and conscience of viewers. The works of this brilliant and complicated man remain a plea for the causes of social justice and a testament to the art of photography.

Born in Wichita, Kansas in 1918, Smith learned about photography from his mother, Nettie. By the age of thirteen he was committed to the craft, and by twenty-one he had been published in dozens of magazines. A breakthrough for Smith came during World War II, when he received an assignment to cover the war in the Pacific. In the spirit that characterized his lifelong approach toward his work, Smith threw himself into the action. He photographed on land, in the sea, and in the air, hoping to get to the center of the experience of war, and, in his words, “sink into the heart of the picture.”

As he observed and photographed the Japanese victims of the war, Smith’s conscience was stirred. It was then he began to develop in his work the theme of social responsibility. He sought to touch the viewers’ emotions and inspire them to work for social justice. As Smith explains, “I wanted my pictures to carry some message against the greed, the stupidity and the intolerances that cause these wars.” Smith’s wartime work was cut short when he was wounded, and he returned to his wife and children in upstate New York. When he was ready to work again, he felt he “needed to make a photograph that was the opposite of war.” The photograph, “The Walk to Paradise Garden,” was of his son and daughter stepping through the woods into a clearing. It proved to be one of Smith’s most enduring and best-loved photographs.

After the war, Smith undertook a series of photo-essays for LIFE magazine. Smith would spend weeks immersing himself in the lives of his subjects. This approach, very different from the usual practices of photojournalism, reflected Smith’s desire to reveal the true essence of his subjects. For “Nurse Midwife,” the story of Maude Callen, a black woman working in an impoverished community in the rural South, Smith wanted his essay to “make a very strong point about racism, by simply showing a remarkable woman doing a remarkable job in an impossible situation.” Smith’s method of getting close to his subjects and photographing them from a more intimate perspective proved successful. There was a tremendous response from both his editors at LIFE magazine and the public at large.

Smith, however, still felt a strong need to separate from the strictures of the magazine industry and work as an independent artist. In 1956, Smith left LIFE magazine and began work on an ambitious study of life in Pittsburgh. When asked to provide photographs for a book on Pittsburgh, he envisioned the project in epic proportions, planning a broad, multi-themed approach that would show the city as a living entity. He threw himself obsessively into the work, making more than ten thousand photographs, of which only fifty were used. The Pittsburgh project drained him physically and financially, and he was never able to publish the project in a form that achieved his vision. The experience, while difficult, represented a breakthrough for him; as his biographer, Jim Hughes, points out, it “allowed him to continue viewing himself in terms of art rather than journalism.”

Smith fully embraced the artistic life in the late fifties, leaving his family and moving to a loft in New York City to devote himself to his work. For the next decade, Smith spent most of his time in his loft, taking pictures from his window of the life in the streets, and photographing the artists and musicians who shared his lifestyle. This period culminated in an acclaimed retrospective of Smith’s work, titled “Let Truth Be the Prejudice”, at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1970. Soon after, Smith began work on what would be his final project. Working with his second wife, Smith spent several years in Japan collaborating on a book about victims of industrial pollution in the fishing village of Minimata.

When W. Eugene Smith died in Tucson, Arizona in 1978, he left behind a legacy of some of the most powerful photographs in the history of journalism. His personal approach to integrating his life into the lives of his subjects revolutionized the somewhat new form of photojournalism known as the photo essay. His body of work remains one of the primary bridges between photojournalists and fine art photographers. In the end W. Eugene Smith’s greatest gift was his life long insistence that journalistic photography always search for the depth and humanity of its subjects.