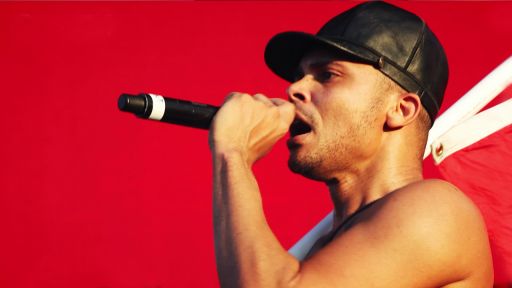

“I feel like I’m one of the last,” Walshy Fire told me when we spoke back in 2019.

The world-renowned DJ, producer and dancehall veteran had just stopped by the New York City offices of TIDAL, the digital streaming platform where I am the editor and curator responsible for dancehall and reggae music. He wanted to play me some tracks from his latest album “Abeng,” and talk about how he’d concocted this fresh fusion of Jamaican and African sounds.

I could feel the sincerity in Walshy’s voice, but I didn’t quite understand his meaning. What exactly was he one of the last of? After all, Walshy is a man of many talents. For over 20 years, he’s been rocking the turntables, the mixing board and the microphone for internationally known sound systems like Major Lazer and Black Chiney, back when he was known as “Walshy Killa.”

Born in Miami and raised in Kingston, Leighton Paul Walsh grew up immersed in sound system culture, which started in Jamaica and spread all over the world—giving birth to hip hop, reggaeton, Afrobeats, EDM and many other diverse genres along the way. When most people think of Jamaican music, Bob Marley comes to mind. But as Marley himself once sang, “half the story has never been told.”

Growing up the way he did, it’s no wonder that Walshy became the third member of the Major Lazer crew when Diplo, an eclectic DJ/producer from Tupelo, Mississippi, started dabbling in island sounds. Having someone steeped in Caribbean-American culture on the team gave authenticity to Major Lazer’s mash-ups of dancehall and EDM. With Walshy on board, the collective produced massive hit records that blended hardcore lyricists like Vybz Kartel, Busy Signal and Shatta Wale with pop icons like Beyoncé, Justin Bieber and J Balvin.

Over the years Major Lazer influenced the music business to get more bold in experimenting with new sounds. These days reggae and dancehall are pretty much mainstream, from Drake to Nicki Minaj to Janelle Monae’s latest album—which mixes reggae and Afrobeats.

Walshy Fire deserves some of the credit for that shift in popular culture.

The last time Walshy stopped by TIDAL, he’d recently co-produced “Toast,” the breakout hit for a new Jamaican sensation named Koffee. Walshy discovered the teenage talent while she was visiting Miami, paired her with the upcoming producer IzyBeats, and the rest is history. Koffee is now one of the biggest artists in the space—collaborating with pop stars like Sam Smith, recording movie soundtracks co-written for her by Jay-Z and modeling Calvin Klein underwear. She’s also the first woman and the youngest artist ever to win a Grammy Award for Best Reggae Album.

To spot talent early is a gift. You have to be part of culture, living and breathing the scene every day. Sometimes that’s not as glamorous as it appears. “The truth is nightlife is a ****** quality of people . . . and it’s the space I live in,” Walshy told me. “Think about it. It’s a room completely filled with people doing horrible things—fighting, grabbing a girl’s ass, vomiting. And you’ll speckle in a few amazing people.”

Walshy was in a reflective mood because it was not like any other day. Just one day before his good friend and well-known master of ceremonies Microdon had suddenly passed away, leaving the whole New York dancehall scene in shock. They’d literally been jamming together at Walshy’s Rum & Bass party one night earlier. That same year Walshy had been grieving the loss of his father, his sister, and a friend who’d been murdered. No wonder he was wearing his heart on his sleeve.

The truth is that he’d been trying to shift the frequency of nightlife for a while, channeling the mantra “positive vibes only.” That’s why he changed his name from Walshy Killa, and why he made a habit of stopping the music in a club full of people behaving badly and changing up the experience. “I need everyone to just look at the person they came with right now,” he’d tell them, every night. “Put your hand on their shoulders and say I love you. Give that person a hug . . . Tomorrow is not guaranteed.”

Thinking about the fact that Microdon was gone, I understood what Walshy meant when he said he was one of the last. Microdon did the same sort of thing within New York that Walshy did on a global scale—chatting on the microphone around a sound system, making people feel good despite whatever else was happening around them. “I think emceeing in a party is a dying art, if not almost dead,” Walshy told me. “Microdon was one of the last guys in New York City keeping it alive, so he’ll be missed.”

Pull Up is a good title for the In The Making film on Walshy Fire, directed by Alicia G. Edwards. The term is used in the dancehall as a command from the emcee to the selector, telling him to pick up the needle and start the record over again from the top. But for Walshy it means something else too—pulling fresh talents up into the spotlight, pulling everybody’s vibes up to a higher level.

That is why I was so glad to hear his final words in the doc. “I’ll never stop doing what I’m doing, and doing it to the best of my ability every single day,” Walshy says. “It’s never gonna stop.”

Check out Walshy Fire’s Essentials in this playlist.