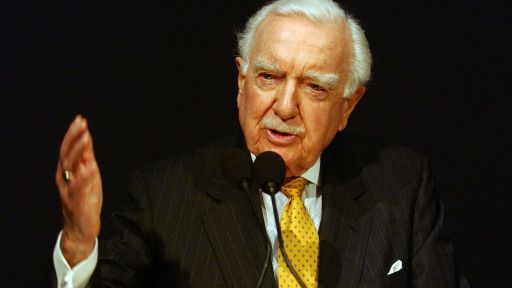

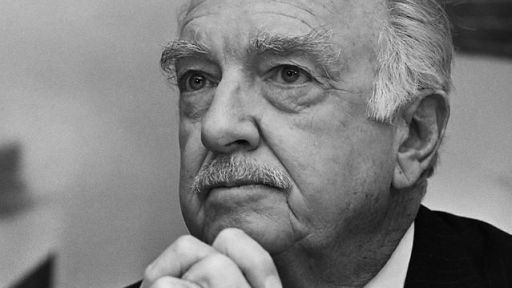

“Walter’s career curve and the curve of network television absolutely dovetailed. And, and he held that position for so long under such vastly changing circumstances … that it seemed to most people that as they got their first television set, Walter and CBS NEWS had joined their family.”

— Historian and journalist David Halberstam

He was the man who told us that President Kennedy had been shot, the man who told us that we had put a man on the moon, and the man who told us that we couldn’t win the war in Vietnam.

During the 20 years he anchored the evening news on CBS, Walter Cronkite became a daily presence in the American home. Building on the legacy of Edward R. Murrow, he brought CBS to the pinnacle of prestige and popularity in television news. And when he left CBS, both began to ebb away.

Walter Cronkite’s life and his work followed a simple, consistent line. At the age of 12, he read about a foreign correspondent in BOY’S LIFE and decided that was what he wanted to be. It was a modest aspiration, the only career goal he ever had, and he achieved it by becoming the first important news anchor on American television. That achievement and the everyday work it involved made him happy, and he had the innate good sense not to be arrogant about it. Indeed, his modesty and his dedication were the reasons his wide audience liked him so much — and trusted him.

It isn’t enough to say that he was the “most trusted man in America,” as determined by a 1972 Oliver Quayle poll.

In fact, in a many-headed questionnaire, he beat the president and vice-president of the United States, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, the Democratic candidate for the presidency (Senator George McGovern), and all other journalists. And this accolade came at the height of the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. In those years of anger and division, Americans simply believed that Walter Cronkite would not knowingly deceive them.

Cronkite — born in Missouri but raised in Texas — got his training as a journalist with the United Press wire service. He had had other jobs before it, with small newspapers and small radio stations. But the UP was his spiritual home and would remain so, in large part, for the rest of his life. There he learned to get the facts accurate, write them simply, and get them on the wire quickly.

In December 1941, right after Pearl Harbor, he signed up as a war correspondent, got his uniform, and headed for Europe on the U.S.S. TEXAS. He covered the air war against Germany from England and the Allied invasion of North Africa from the deck of a ship bombarding the Moroccan coast. When Cronkite returned to New York after the invasion, Paramount put him in a newsreel reporting on the North African campaign. Even then, he was good at it. Sincere, straight, no curlicues.

Edward R. Murrow was following his career and liked what he saw: a hard-working young wire service reporter who’d go anywhere and do anything for a story — even ride a bomber or a glider into combat. But Cronkite turned down the legendary CBS newsman and the prospect of a glamorous career in radio to stay with the workaday United Press. Years later, after the war, after Cronkite had covered the Battle of the Bulge, the end of the war, the Nuremberg trials, and the beginnings of the Cold War from Moscow, Murrow again offered him a job, this time on television. This time, Cronkite took it.

It was, according to historian David Halberstam, “one of those things that really worked. Right man. Right place. Right time. Right instrument.” Television was an unknown, but it was growing. It needed gravity, a tone, a voice, and Cronkite gave it all three. Because nobody really knew what television could do at the beginning, Cronkite was in a position to make it up as he went along and to establish the strict news standards of print journalism. His reports on the 1952 Democratic and Republican conventions were masterpieces of analysis, suspense, and story-telling.

“It’s interesting about the camera. You either have IT on television or not. It’s a kind of chemistry,” said journalist and colleague Bill Moyers. “The camera either sees you as part of the environment or it rejects you as an alien body. And Walter had IT, whatever IT was.” Cronkite could go on the air live and talk about what was happening without a script or notes, never repeating himself, always adding a little more information, filling time between events, coordinating the coverage of roving reporters on the convention floor. By the time the 1956 conventions began, Cronkite was as well-known as the men he was covering.

His early fame got a huge boost from a popular program peculiar to the early days of television: YOU ARE THERE.

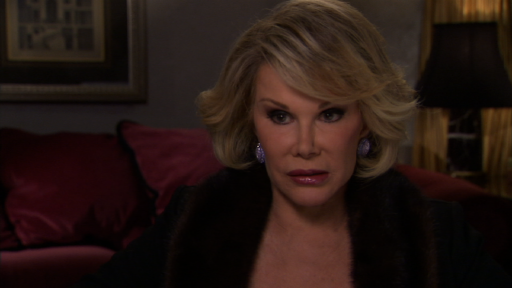

Each week a team of CBS correspondents — headed by Cronkite — would “report” on a critical historic event: the death of Julius Caesar, the Louisiana Purchase, the Salem witch trials, or the trial of Galileo. Reporters would “interview” Sigmund Freud while he was analyzing a patient or Joan of Arc on her way to the stake. Every show would end with the same, soon-to-be-familiar refrain from Cronkite: “What kind of a day was it? A day like all days, filled with those events that alter and illuminate our times. And you were there.”

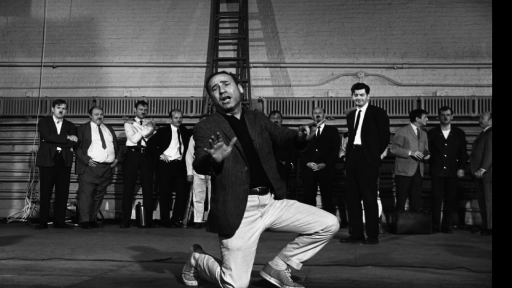

The director of the series was the young Sidney Lumet, who would go on to create such award-winning feature firms as TWELVE ANGRY MEN, NETWORK, SERPICO, and DOG DAY AFTERNOON. He chose Cronkite for the role of anchorman “because the premise of the show was so silly, was so outrageous, that we needed somebody with the most American, homespun, warm ease about him.”

The same qualities got him the job as anchor of the CBS EVENING NEWS in 1961. At the time, the broadcast — like the news broadcasts of the other networks — was just 15 minutes long. But Cronkite wanted the networks to be responsible citizens, to take the news more seriously, to devote more time and more funds to news — whether that commitment made them a profit or not. He also wanted the title of Managing Editor so that the staff and the audience would know that the news judgment on the program was his.

By 1963 he had the title and the longer broadcast. Cronkite inaugurated the new, longer format with a feature with President John F. Kennedy in September 1963. Two months later, Cronkite broke into the broadcast of the soap opera AS THE WORLD TURNS to announce that the president had been shot in Dallas, Texas. Sitting behind the news desk in his shirt-sleeves with his glasses on, Cronkite continually updated the story. On a videotape of that historic broadcast, occasionally a hand can be seen pushing a wire service report, a photograph, or a correspondent’s report into Cronkite’s hand.

Throughout the morning, he calmly filled in the story, squelched any information that hadn’t been verified, reduced speculation to certainty — until he was handed a dispatch confirming that the President of the United States was indeed dead. He pulled off his glasses, looked to the clock to repeat the time, and seemed to subdue a sudden wave of emotion, before he continued with the broadcast.

The assassination was on a Friday. All of America watched this event together. Whether in California, Nebraska, or Mississippi, the entire nation was seeing the same thing — for three days. Saturday, Sunday, Monday … the networks ran nothing but coverage of the president’s death, the return of his body to Washington, the funeral procession to the Capitol, and the final journey of President Kennedy to his burial in Arlington National Cemetery. There were no commercials for those three days. By today’s standards, the coverage was simple and sedate. No emotion was added to the trauma of loss, nor was any needed.

It was a show of dignity that America never forgot. And, as a result, Americans awarded Cronkite the honor of allowing him to give us the bad news about our world as well as the good. This messenger was not condemned when he reported that America’s deeply racist history had to change. And he was not punished in the ratings when he went to Vietnam and reported that he had seen the lies, corruption, and stalemate in that war and that it was time for us to go.

President Lyndon Johnson listened to Cronkite’s verdict with dismay and real sadness. As he famously remarked to an aide, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost America.” After all, this was not one of the young, brash reporters like Morley Safer or Jack Laurence pricking the president’s power. It was Cronkite, veteran of World War II, a man of unimpeachable patriotism. When he stated the obvious — that the Viet Cong had no intention of giving up, and we had no intention of remaining in Vietnam for another generation — the common sense of it stuck with the public.

For more than a year, Johnson had been losing popularity due to the war that he could neither win nor end. But when he announced his decision not to run for re-election, just about everyone put it down to the influence and power of Cronkite. His integrity and clear judgment gave him tremendous authority, remarkably, with the old and the young, the conservative and the liberal. He transcended all those divisions. As Senior PBS Correspondent Robert MacNeil observed, “Cronkite came to be the sort of the personification of his era and became kind of the media figure of his time. Very few people in history, except maybe political and military leaders, are the embodiment of their time, and Cronkite seemed to be.”

Cronkite could report with disgust the Chicago police attacks on anti-war demonstrators at the 1968 Democratic convention. And he could report with unalloyed delight the landing of a man on the moon. He could withstand the attacks of Vice President Spiro Agnew against the so-called “nattering nabobs of negativism” of the press by speaking eloquently not only of “freedom of the press” but also, as he emphasized, of “the important right of the people to know what their government is doing in their name.” And to prove that he meant it, Cronkite picked up the WASHINGTON POST’s early article on the “Watergate Caper” and made the story national news with a two-part feature on the EVENING NEWS in the fall of 1972, just a month before the election.

A furious White House threatened to punish CBS by revoking its station licenses. But CBS stuck by its story and watched as Nixon self-destructed over the next two years. Cronkite reported with quiet admiration the thoughtful proceedings of the House Judiciary Committee on the Impeachment of President Nixon. And he reported Nixon’s resignation with sadness. There was no gloating, nor hard feelings. He was a professional doing his job, which he never doubted was serving the public.

There was no one, it was said, that he couldn’t get on the telephone. And in 1977, he got new Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to agree to an interview. In his autobiography, Cronkite described the hot afternoon on the banks of the Nile: “The interview was as tepid as the afternoon was hot. Sadat droned on about his hopes and plans for Egypt’s future as I fought to stay awake. Suddenly he brought me bolt upright. I was sure that I had heard him say he intended to go to Jerusalem. Yes, he assured me, he would go to Jerusalem.” Sadat was the first Middle Eastern leader to make any such gesture toward peace. Cronkite set up phone calls between Cairo and Jerusalem and flew with Sadat to his historic meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin.

When Cronkite resigned in 1981, his audience didn’t really believe it — or want to believe it. It was, wrote a commentator in THE NEW REPUBLIC, “like George Washington leaving the dollar bill.” There were so many requests for interviews and photographs of the departing Cronkite that eventually all were denied. On the final broadcast, he assured his audience that while they would be seeing less of him, he would not be disappearing.

This is my last broadcast as the anchorman of the CBS EVENING NEWS.

For me it’s a moment for which I long have planned but which nevertheless comes with some sadness. … This is but a transition, a passing of the baton. A great broadcaster and gentleman, Doug Edwards, preceded me in this job and another, Dan Rather, will follow. … Furthermore, I am not even going away. I’ll be back from time to time with special news reports and documentaries. … Old anchormen, you see, don’t fade away, they just keep coming back for more. And that’s the way it is, Friday, March 6, 1981. I’ll be away on assignment and Dan Rather will be sitting in here for the next few years. Good night.

But Cronkite was on the air less and less. “Walter was a tough act to follow,” CBS colleague Mike Wallace said, “and when Dan Rather started to take over the EVENING NEWS, he didn’t want Walter sitting there. I think, candidly, he just didn’t want Walter being the wise man looking over his shoulder. And I think that disappointed Walter.”

Though he was off the air, he was not silent.

“There comes a time,” says journalist Bill Moyers, “when, having covered the world for all of your life, you want to reach and state the conclusions to which your life’s experience has led you.” And, freed from the restraints of objectivity, Cronkite has done and still does just that. The war on drugs, he said, succeeded only at putting young people in prison. Global warming is a fact, he said, and, regardless of the cost, the entire world should support the Kyoto treaty. It is not only immoral to kill one another in wars, he said, “even the matter of defense expenditures is immoral. To spend that much money … in building more refined systems of murder is not a civilized consideration.” “In the wake of 9/11, the desire for revenge against Islamic fundamentalists is both understandable — and dangerous. Without intending to, the United States could become mired in Middle Eastern wars for decades.”

Always he speaks out for the right and the duty of the citizen to know what is going on in the world. It is a stark moral code he holds up for the reader and the reporter alike. The conceit of the powerful is not the reporter’s concern. A good journalist has only one job — to tell the truth.

Cronkite set the standards of television news when the medium was new and malleable. He was loyal to those standards, and his large audience was correspondingly loyal to him. “He seemed to me incorruptible,” said director Sidney Lumet, “in a profession that was easily corruptible.” It was all that Cronkite wanted — and he achieved it.

© 2006 LESLIE CLARK, co-producer, Walter Cronkite: Witness to History