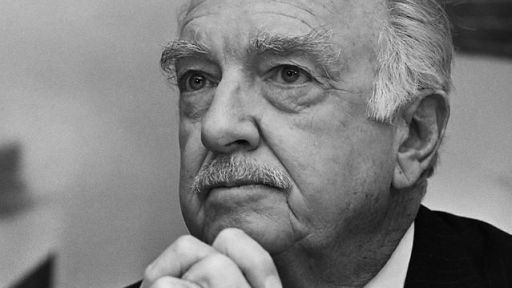

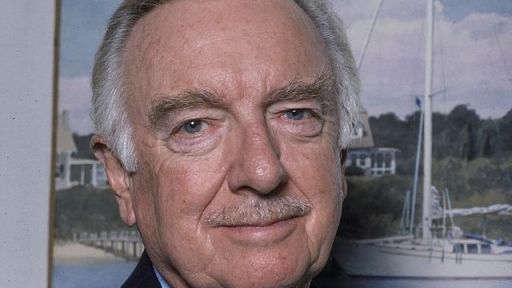

Q: Walter Cronkite leads such an incredible life. With so much material to choose from, how did you determine your particular approach to this film?

A: That was one of the big challenges, because there is so much material and he covered really the whole second half of the 21st century. I decided that instead of doing an overview of his whole history and career, I would just pick highlights and offer an in-depth look at those moments and what was happening in terms of news reporting around that period.

Q: Can you discuss some of those highlights?

A: He went to Vietnam in 1965 and, like many reporters, was listening to what the military was telling the press and was reporting from that standpoint. And he was also getting reports from Morley Safer, Mike Wallace, Jack Lawrence, and other journalists who were working for CBS. Cronkite, who was very smart and knew a good story, started having some serious questions. During the Tet Offensive, he went back to Vietnam, and that was when he aired his Vietnam reports. He said he felt this was a stalemate situation and that we might want to rethink how we were dealing with Vietnam. It was a big shock to President Johnson, who would eventually say, “If I’ve lost Walter Cronkite, I’ve lost America.”

One thing that surprised me is that his report after Vietnam was actually not his idea. In fact, when he came back he was quite troubled, and Frank Stanton said, “You know, Cronkite, I think you should really tell the audience what it is that you saw in Vietnam.” Cronkite had always been rigorous about maintaining his objectivity and not crossing that line, but he was encouraged to actually express himself. It really was a courageous act.

Q: What about his reporting on Watergate?

A: Watergate was being reported brilliantly by THE WASHINGTON POST, but it was so complicated that not many television newscasters were picking up the story. You would just see little bits and pieces. What Walter did — as Murrow did with the McCarthy hearings — is take a stand and say, “We need to do a couple of special reports on Watergate and try to report the facts as we see them and as we know them.” He used much of the reporting from THE WASHINGTON POST. And the POST credits Walter with having helped them get the story out to major papers around the country. So his reporting was very helpful in inspiring other people to cover the story.

Q: Wasn’t there an issue with CBS Chairman Bill Paley over the Watergate stories?

A: Paley got a call from the White House after the first broadcast, and there was some concern about the report. But Cronkite did not know because his producer handled it. I think they wanted to keep it away from Walter because it was a difficult situation. Basically, Frank Stanton found a solution, which was to shorten the report. But they didn’t change what was being reported. So they were able to say to the White House, “Yes, we’ve made some changes.” Cronkite didn’t hear about this until after the fact.

Q: Cronkite witnessed the birth of TV news all the way through the explosion of cable. What change do you think made the biggest difference in the evolution of TV news?

A: The story we’re telling in the film is about when news was reported by the three networks. As Daniel Schorr said, “It was like a national seance.” That was it. That’s where you got your news. Those reporters, those anchors, were the people you went to for the news. Now we have so many anchors and so many different ways to report the news. We have some cable channels that actually have a political position and are preaching a certain agenda. So I think the big change is that people don’t trust the anchors like they used to.

Q: In January, during early promotion for the film, Cronkite went on record about Iraq and what he sees as the futility of that war. Did you include such viewpoints in the film?

A: It did come up, and there are small references. But because I want this to be a bit of an evergreen, we’re not really focusing on the Iraq war. I think that ties it too much to a specific time. But there are many echoes in terms of how history repeats itself. People are not going to be able to avoid seeing parallels with Vietnam.

Q: Has Cronkite become more outspoken now that he’s been freed from the shackles of objectivity?

A: Yes, and I asked Bill Moyers in the film why Cronkite has become more outspoken. The fact is that he is someone who has seen and experienced so much history. Now that he’s not an anchorperson any more and he’s not in a position where he has to maintain that objectivity, I think he feels free. Actually, it’s more than just freedom. I think he feels that it’s a responsibility, which is something Moyers was saying, that at a certain point you have the maturity, you have the history behind you, and you are in a position to be able to offer some insights to your time.

Q: Did Cronkite share anything unexpected with you?

A: I didn’t know he was such a Walter Mitty character. I’ve always seen him as a serious broadcaster. And I didn’t realize what a great bon vivant he is, how he loved to race cars, how he loves sailing. And he’s physically brave. In World War II, and even in Vietnam, he put himself out there. With the space program, he did the same training as the astronauts. There’s a piece of Cronkite that’s totally courageous. He seems fearless — someone who embraces life with gusto.

There was also this wonderful story, which I’m not sure I’m going to be able to include in the film, of his memory of something he wrote during World War II, when he became very close to a squadron of pilots. A plane returned with the captain killed, and Walter wrote a story about that flight. Even as he retold it you could see his compassion and his complete connection to the human story. You could see it on his face. Here’s a man who’s seen so much and still has all that emotion and can feel so much. That’s the real reason people responded to him on the nightly news — there is this humanity about him that he allows you to see. He’s not just a cold journalist. (See the video: Cronkite discusses the inspiration for his famous story: Nine Crying Boys.)

Q: You reviewed a massive amount of archival material from Cronkite’s days at CBS. What are some of the gems you discovered?

A: What I found, which really made me nostalgic for that time, is that over and over in the reports on people like John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, you find speeches that were full of literature and metaphors. They were literary works of art. They didn’t talk down to the public. And Cronkite never talked down. He presented the news in a way you understood, but at the same time, he would quote poetry. In one of the space documentaries, he quoted Archibald MacLeish. So you had the feeling that during that time there was appreciation for a different kind of language, and it was really inspiring.

Q: In your opinion, what makes Walter Cronkite an American Master?

A: I think Walter Cronkite is an American Master because he represents the sort of ultimate television newsperson in the sense that Edward R. Morrow represented radio. Cronkite did that for television news, and he was the one who really developed the whole network news format. He was the one who put the news in the newsroom.

Q: Most people associate Walter Cronkite with news, but he’s led a very rich life outside the newsroom. How is that addressed in the film?

A: The other big story is his reporting on space, which he had an enormous passion for. That is the piece that I would say really shows his talent beyond anchorman. After he left the anchor desk, he was very concerned about the environment, very concerned about education. And then we have him conducting. He enjoyed conducting orchestras and he conducted the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. He has a passion for music. And sailing. He took up sailing after he had to stop racing cars. It was getting a bit dangerous, so he took up sailing.

Q: What did you learn from interviewing Cronkite’s contemporaries?

A: A really important point in this documentary is how reporters like Cronkite, and all the other greats I interviewed, were mostly people who came out of print journalism. They were real reporters. And that transition from print to television gave them an understanding of how to find and present a great story. Their print background is reflected in the language they use in their reporting. There’s real writing there.

Q: What did Cronkite’s children, Chip and Kate, tell you about their father?

A: They certainly said he made time for them, but what was clear is that it was a challenge for them to be the children of Walter Cronkite because he was so famous. Everywhere he went, he was a star. And I think it’s hard for kids. Kate Cronkite wrote a whole book about it. Chip Cronkite has his own production company. Both of them were very helpful with the film, Chip especially. He’s been extremely generous in sharing a lot of his research and archival materials and very supportive in trying to give me everything he can to make this film on his father.

Q: Do you think we’ll ever see the likes of Walter Cronkite again?

A: No. Times have changed. I don’t think today’s medium allows for this kind of reporter. We’ll never go back to three networks. Now, it’s totally different.