The following is excerpted from director Richard Schickel’s book, You Must Remember This: The Warner Bros. Story, upon which his film is based.

You could argue that this book, and the television series from which it derives has been in the making for something like 65 years. When I was a kid, living in a suburb of Milwaukee, the neighborhood theaters nearest to me obviously had some sort of arrangement with Warner Bros. and played more movies from that studio than from any other. Somehow, for reasons I couldn’t quite understand, they appealed to me more than any of the competition’s offerings. I didn’t know exactly what a director did, but I do know that I particularly liked movies signed by Michael Curtiz, Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh better than I did those of other filmmakers; they were, I think, tougher, grittier, a little more darkly romantic than their competitors. And then there were the stars. I loved gallant Errol Flynn the best, but James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart were close seconds. I even liked Bette Davis. Little boys weren’t supposed to care much for “women’s pictures,” but there was something about her — her feverish intensity somehow transcended her genre.

What I’m saying, I guess, is that the studio had a character that I couldn’t quite define, but was yet palpable and pleasing to me. Later, looking back at that period, it was the Warner films that I recalled first — Casablanca, of course, and Yankee Doodle Dandy, but also They Died with their Boots On and Gentleman Jim, and the wartime adventures like Air Force and Destination Tokyo and Action in the North Atlantic. I can discern now what I most treasured about these films. They were movies that to greater or lesser degree defined what it meant to be male for little boys who had many questions on that subject. They made imperatives out of the antithetical qualities of stoicism and rebelliousness, out of being alienated from the community, but eventually learning to reconcile with its values without loss of individuality.

Later, when I began working on television programs, the first two that I did revolved largely around Warner films. After that, when I began making television profiles of major American directors, many of them were about Warner directors — beginning with Raoul Walsh and continuing through Clint Eastwood. Through their careers, I forged a deeper identification with the studio — a sense that its story is crucial to the history of American movies, even to American social and cultural history — that is to me unbreakable. Which is why the opportunity to make a film about the long history of the studio seems to me the capstone of my career, the place to which it was all along heading.

This is not to say that there were no surprises for me as I worked on this project. I have come across wonderful movies — The Hard Way, Roughly Speaking, The Damned Don’t Cry — that I had never seen and scarcely heard of — that have powerfully gripped me. I have re-examined movies (like I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang) and careers (like Doris Day’s or the director Vincent Sherman’s) that now seem greater than they formerly appeared to me. And I have also been able to delve into the fractious life of the studio, which often had all the logic of a cat fight in an alley. Out of this work — which has never seemed like work to me — a somewhat more sophisticated understanding of what the studio was doing, what its hold on me and others like me consisted of, has emerged.

It’s perfectly obvious to everyone that in Hollywood’s classic age, the 1930s and 40s, Warner Bros. was the working class studios. You can see that most obviously in its famously “tragic” gangsters, machine-gunning their way to power only to be gunned down not so much for their depredations, but for their hubris, for daring to challenge the respectable and the law-abiding. Other studios made pictures of this type, but few of them matched the energy and fervor of the Warner movies. More important, these competing films did not emerge out of the context Warner Bros. supplied. Think Baby Face, about a sexually abused working class woman who takes loveless revenge on bourgeois and upper class men as she sleeps her way to the top of a banking empire. Or Wild Boys of the Road, about homeless children wandering the nation, endlessly harassed by the police as they search for jobs and a place to rest their heads. Or Heroes for Sale, in which a hardworking man loses everything — his family, his business — under the impress of the Great Depression, then simply disappears in the American fastness. Or Black Legion, in which a working stiff becomes the murderous tool of Ku Klux Klan-like organization.

Consider, as well, wartime Warner Bros. with its small, ethnically balanced fighting units bonding together in passionate defense of the American community, now threatened by external rather than internal forces. Again, other studios made films of this kind, but not with the conviction of Warner Bros. One thinks, for example, of MGM, the most prosperous of the Hollywood studios. It was a place committed to glamorous stars and deluxe mis en scenes. But there was always something smug, self-satisfied about its pictures, something more purely escapist in its intentions. They didn’t do social conscientiousness in Culver City. Or take Twentieth Century-Fox, with its commitment to nostalgic sentiments and rural sweetness. Sure, it took up serious matters (see The Grapes of Wrath or The Ox-Bow Incident), but its more typical offerings headed toward the ameliorative ending. At Warner Bros. the hero or the heroine tended to end up dead or at the very least marginalized or otherwise dismissed by polite society — and I’m not just thinking about all the doomed mobsters James Cagney played. I’m thinking about Bogart’s romantic devastation in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca and the tragic conclusions of movies as disparate as They Won’t Forget or Dark Victory. Or the misplaced passions of actors as disparate as John Wayne in The Searchers or Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce, of the madness that attends the end of Bogart in Treasure of the Sierra Madre or Cagney in White Heat. I’m thinking of the devastation that concludes The Wild Bunch and Bonnie and Clyde and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, of the existential chill, the air of fated hopelessness, that hovers over Stanley Kubrick’s work for the studio. I’m even thinking of the Dirty Harry‘s radical disaffection and loneliness and of William Munny’s — well, all right — “dark victory” at the end of Unforgiven or the bleakness of the conclusions to more recent Eastwood films like Million Dollar Baby or Letters from Iwo Jima.

A studio as fecund as Warner Bros, makes many films in many different genres over the course of a long history that embraces several managements, diverse economic and social challenges — and, indeed, television, is somewhat slighted in this book. TV is vital to the continuing economic success of the studio, but, frankly, it lacks the drama, excitement and memorability of the movies. I cannot prove that there is some sort of DNA that, unacknowledged, has conditioned the studio’s choice of movie material. But neither can I deny that in its best work, the work that causes us to celebrate its past at this moment, there is a persistent attitude that marks Warner films from the studio’s beginnings until today, an attitude that is much more difficult to find in its television series. It would be ridiculously pretentious to label that spirit “a tragic sense of life.” These guys are in the movie business for god’s sake. They must outguess popular taste every day of their working lives, else they will not long be in the movie business, so naturally they must from time to time embrace the merely cheerful. Or the outright vapid.

But the best Warner tradition is a realistic one, scrappy, contentious and not immune to doom. And if the logic of their stories demanded dismayed romance or diminished hopes or death itself, then the good Warner pictures went there — perhaps because the founding brothers always thought of themselves as outsiders, fighting their way in from the Hollywood fringe. They became successes, and as a result learned to live large. But they did not entirely forget their first-generation immigrant roots, never entirely abandoned the notion that most Americans live only a step or two away from economic disaster, are never invulnerable to those other devastations of fortune that plague even the most privileged of humankind.

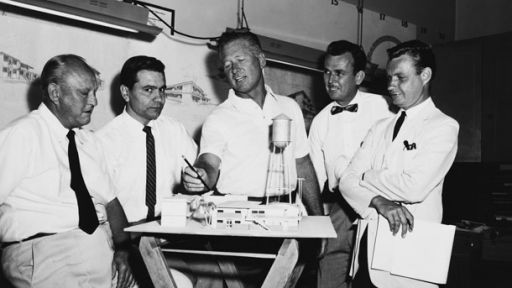

Warner stars were never the prettiest or the most handsome. Indeed, you can’t quite imagine a Cagney or a Robinson or a Bette Davis — odd balls, all in looks and manner — building substantial careers elsewhere. And that says nothing of George Arliss. These were not people we envied or mooned over. These were people we identified with. Nor can you imagine another studio employing as many politically radical, personally disaffected, writers. Or think of someone as angry, stubborn and unpredictably gifted as Michael Curtiz making a thirty year career anywhere else. You can’t tell me that something of the dark and problematic tradition they established does not continue there. I think it’s probably in the water that the tank — the studio’s most famous landmark, decorated with it even more famous shield logo — supplies the place.

When writer-director Andrew Bergman, who had previously written a smart little history of 1930s Warner Bros., first drove on the lot (to co-write Blazing Saddles) he confesses to misting up. It was like coming home for him. I know what he’s talking about. I never enter the gates of the studio without similar feelings. I’ve devoted more of my life to thinking about the movies than I care to admit, and most of my career to writing about them or making films about them. And this is the place where those feeling live most happily, most intensely. I hope some of that passion inhabits my history of Warner Bros, and informs and inspires both my film series and this book.

–Richard Schickel, February 23, 2008