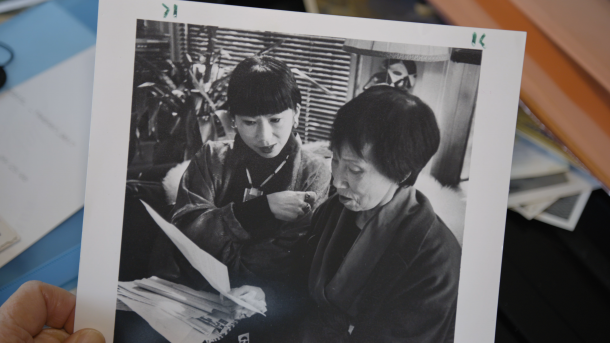

When Amy Tan first ventured into creative writing, she was on a mission. Tan had spent most of her career as a freelance technical and marketing writer — creating ad copy, direct mail campaigns and various materials for telecommunication companies. She was working nearly 90 hours a week and had made a successful career for herself. Still, there was something missing: she lacked passion in what she was doing. She simply was no longer interested in the work that consumed so much of her time and her energy. She ached to do something she truly cared about, something that mattered to her. That’s when she discovered creative writing. “I was looking for something more meaningful, and that’s why I started writing fiction.”

As soon as she began to write for herself, Tan found what had up to that point been eluding her. She became compelled by her work. For the first time, she felt like writing was a gift – a way to better understand herself, her family, and the world in which she grew up.

“The things I discovered about writing at that point were so important to me. It was the notion that you could write and find out what you really believed and felt. All these things that had been submerged, they just came out. And it was through fiction, because fiction gave you a place of safety. It wasn’t about you, it was about these characters. But, it was about you…And at that point, I knew I would write for the rest of my life.”

Not long after Tan discovered her true calling, she received a phone call informing her that her mother had suffered a heart attack. She felt overcome with despair. She worried that she’d missed her chance to hear her mother’s stories, to bond with her on a deeper, more meaningful level. She promised God that if her mother survived, she would truly get to know her.

As it turned out, her mother hadn’t had a heart attack after all. She had been hospitalized with chest pains after a stressful trip to the fish market, but she would be fine. Awash with gratitude and relief, Tan decided to keep her promise to God. She would listen to her mother’s stories. Really listen. And she would write about her.

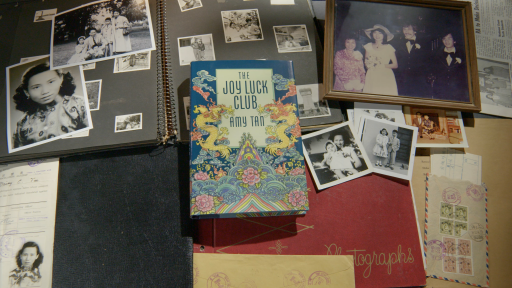

From there, “The Joy Luck Club” was born. This novel, which consists of eight intertwined Chinese American mother-daughter stories, would launch Tan head on into celebrity status as a writer and win her widespread literary acclaim.

Tan wrote “The Joy Luck Club” to better understand and honor her mother, with whom she often had a strained relationship. In exploring the theme of relationships between Chinese immigrant mothers and their American-born daughters, she gained profound insight into her mother’s unique challenges as a Chinese immigrant living in America. She had no idea the impact that these stories would have on other Chinese Americans, writers of color, and immigrant families.

The novel became an instant best seller, and was initially met with enormous praise. It resonated with people from every background, every walk of life. It was among one of the first novels authored by an Asian American writer to become a mainstream success. It was honest, vulnerable, and universal.

The author Isabel Allende remembered reading Tan’s novel for the first time and seeing the similarities between her own Latin American family, “Those grandmothers are like my grandmother and that makes it so close, so personal, so touching in so many ways, and I think that’s what every reader feels anywhere in the world, in any language, when they read Amy.”

While Chinese Americans recognized an authentic voice in Tan’s writing, non-Asian Americans also saw the humanity in the characters whom they realized were not so different from themselves; they shared the same hopes and suffered the same heart aches.

It wasn’t long before the world looked to Tan to represent her entire culture — her entire demographic — all on her own. It was an enormous weight for any one person to carry. “I didn’t seek to be a representative of a whole community of people. I just hoped to write some good stories. And yet, when I was given this mantle of speaking for the Asian American community, suddenly there were these expectations.”

There was also criticism that came from within the Asian-American community. Although “The Joy Luck Club” was applauded for portraying its characters as relatable, human, and authentic, critics felt Tan relied too heavily on Chinese tropes in an effort to cater to Western consumers. They believed her use of broken English, Chinese fables, and stories of concubines were stereotypical and offensive.

“In the beginning, I didn’t know what to say,” Tan said of the criticism. “I would be caught off guard. But then I realized, what they really wanted was role models. They wanted me to right the social wrongs, the social injustices, and finally they had somebody in the limelight who should now address that and not be pandering, so to speak, to the mainstream.”

Initially, the pressure seemed insurmountable to Tan. After all, she had never undertaken to represent an entire culture or to pander to Chinese stereotypes – she drew simply from her own experiences and relationships. “My mother speaks broken English, my grandmother was a concubine,” Tan explained.

Ultimately, Tan decided the best and most realistic option was for her to just write about what she knew and understood. She knew that accurately representing the experience of millions of Asian Americans or appeasing her diverse readership was unachievable. She realized that trying to be an activist as well as a writer would diminish the authenticity of her writing.

Once she returned to her roots and gave herself permission to continue to tell only her own story, Tan was able to put the weight of the criticisms and expectations to rest. “You have to write what’s personally important to you,” Tan said. In doing that, she ensured her ability to continue to breach cultural divides and gift her readers with a rich and authentic glimpse into her world, without apology or reservation.