Some straight cis artists become beloved in the LGBTQIA+ community because of the style of music they make or the ways their lyrics can be broadly applied, because of their visual language and aesthetics, and/or because they particularly embrace their LGBTQIA+ fans.

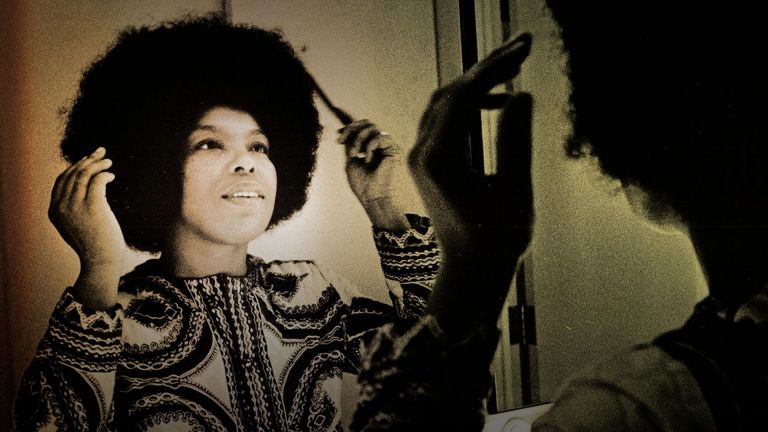

For Roberta Flack, it always went deeper.

At the very beginning of her career, when she was still a schoolteacher moonlighting as a musician, she’d had a regular gig at the Tivoli, an opera restaurant in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington D.C. This eventually ended:

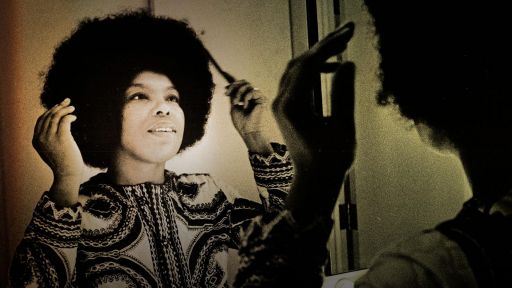

“The Tivoli had closed down and I had decided that I didn’t want to work there anymore anyway, but it had turned me on to another whole world, because it was basically an underground place frequented by a lot of gay people, and these were, of course, very sophisticated people, lovers of opera and fine things—it just opened up a whole new world for me, because they appreciated me so much,” Flack told Chris Albertson for Routes in 1978.

This led her to a new regular appointment at the gay bar Mr. Henry’s on Capitol Hill; she was booked so frequently (“five nights a week, three sets per night,” she told Washingtonian in 2017), that she could finally quit her day job. Other musicians and entertainers, regardless of sexuality, frequently came through Mr. Henry’s—it was on the D.C. map as a cultural hot spot and the place for jazz. This is where pianist Les McCann first heard Flack play; newly signed to Atlantic Records, he tipped off then-Atlantic VP Joel Dorn, who would go on to produce Flack’s classic recordings for the label, and the rest was history.

Flack dedicated her gorgeous version of “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” from her debut album, 1969’s “First Take” to her gay audience. (“A strictly heterosexual reading of [‘Ballad of the Sad Young Men’] would be very anti-feminist, and that’s not where I was coming from at all—it was all gay, straight down the line, I mean that’s the way I did it,” she told Albertson.) Others—from folk singer Davy Graham to Soft Cell’s Marc Almond—have taken on the song over the years. It was written by Tommy Wolf and Fran Landesman for “The Nervous Set,” a now-largely-forgotten musical about the Beat Generation. In its vagueness, it speaks to multiple audiences; Elizabeth Nelson, in a recent review of “First Take” for Pitchfork, mentions its resonance to those returning from Vietnam, and, of course, it was originally about the nihilism and self-destructiveness of the Beats. But it is with gay men that the song has had the longest relationship, no doubt because of both Flack’s version and the centrality of the gay bar to LGBTQ+ history (not to mention the intertwined histories of homosexuality and the theater).

“‘Ballad of the Sad Young Men’ was a staple in Flack’s live concerts,” writes Jason King in his essay “The Sound of Velvet Melting: The Power of ‘Vibe’ in the Music of Roberta Flack”:

“As early as 1971, she openly discussed its meaning in her stage act, lest its impressionistic lyrics be misunderstood. Flack sang songs of substance that had meaning for gay audiences throughout her career. ‘Jesse,’ an ambiguously titled love song by Janis Ian, likely had resonance for Flack’s audiences. In 1982, Flack sang the theme song to ‘Making Love,’ Arthur Penn’s groundbreaking and highly controversial film depicting homosexual love between two men.”

Quoted in The Guardian, Flack herself said:

“I sang [‘Ballad of the Sad Young Men’] about soldiers, then, later, about gay men. It touches me deeply every time. I used to perform this song at Mr. Henry’s and people would be totally silent. I knew it moved them.”

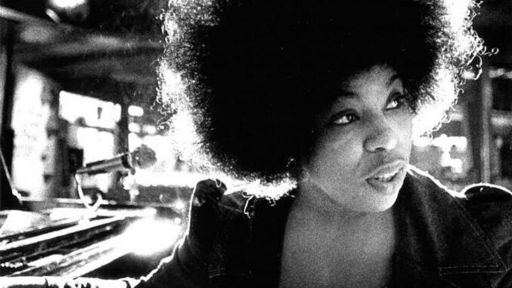

As King notes, though Flack’s music—particularly on her early recordings—was uncompromisingly political, and she took care to frame that in live performances, she’s not broadly read as a protest artist. This is because her music sits somewhere in between soul, folk and pop, bridging all of it with a style of jazz that had been specifically whitewashed and commercialized for the last few decades prior to Flack’s arrival on the scene. Flack’s work, though, calls back to the earlier days of jazz as a politicized and specifically Black art form; throughout her career, she’s always been clear about this.

A particularly poignant quote from the Albertson interview—which is full of them, honestly—sticks out. She’s discussing the structural barriers for Black artists, and the ways in which Black artists have specifically opened doors for one another—whenever you can get access to any kind of power, it behooves you to open it up to those who, like you, are shut out by structural discrimination. And she says: “You see, one of the reasons Black people are not as far ahead in any area in this country, particularly in this country, as we perhaps could be with the talents that we have, is because we are so desperate; once you get there, it’s very hard for you to really open up your heart, your mind, and your soul, and to reach back and bring in everybody that you can—white people do it all the time.”

Flack’s work is both intensely personal and intensely universal, and it is the ability to bring both to bear on a song at once that sets a pop superstar apart from someone who’s merely competent. She consciously includes the most marginalized at all times, connecting along that line of outsiderdom and systemic, multi-generational trauma. And when you hear her sing and play, her technical mastery is always balanced by a direct emotionality.

Nowhere is that more apparent than on her performance of “Ballad of the Sad Young Men.” In other hands the tune can read as maudlin, campy, or just straight up uncool. When Flack sings it, it comes alive with genuine grief and empathy, its smoothness belying the pain that lurks just beneath the surface. She knows how that speaks to us as queer people, and she recognizes that with simple grace. The people’s artist, through and through—who knows that ‘the people’ must include us all, and that her LGBTQIA+ audience has been with her since the beginning and will see her through long past the end.