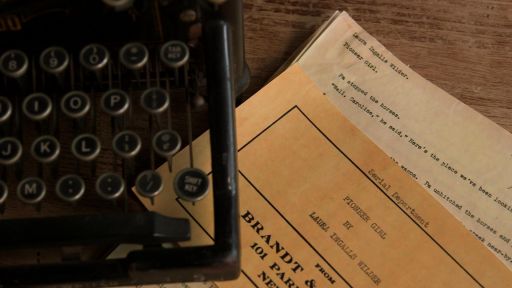

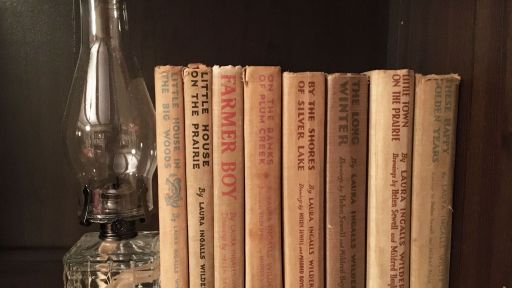

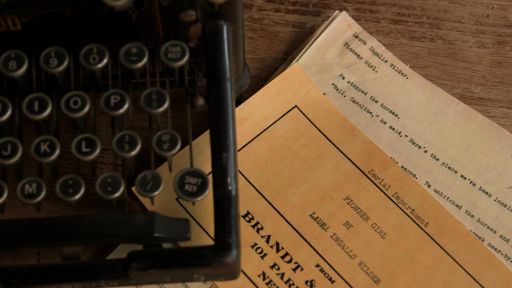

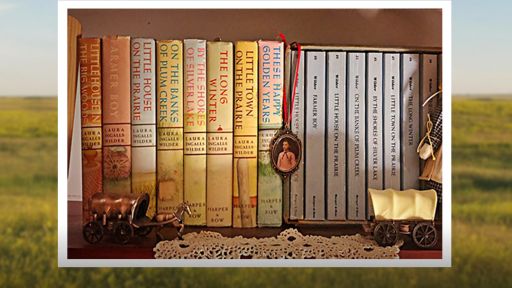

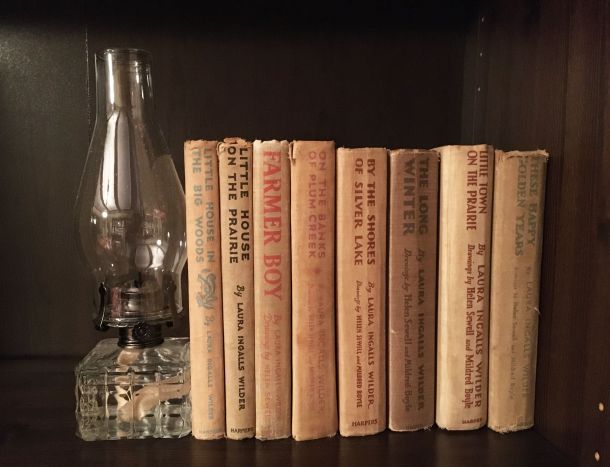

To many fans, the “Little House” book series, based on Laura Ingalls Wilder’s life on the western frontier, captures the spirit of America.

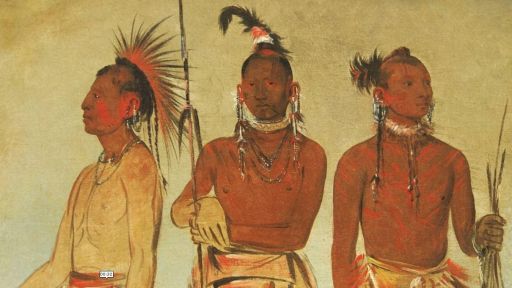

The stories tell a tale of adventure, of quiet resilience in the face of extremes, the excitement of the unknown, and of re-settling and making something of oneself wherever one might land. These stories, of course, were written from one particular perspective. The other perspective is from those Native Americans whose land was stolen and populations decimated to accommodate the so-called “settlers,” but that version is too often ignored. It’s little wonder then that for some authors of color, the books spark both memories of warmth for their literary genius, and also sadness and anger for their troubling depictions of Native and Black Americans.

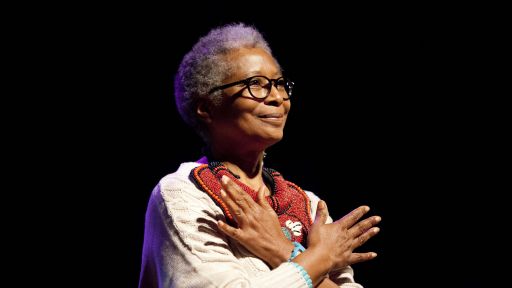

“I think I first started reading the books in 1981, so we had very different sensibilities then,” said author and essayist Roxane Gay. “It didn’t even occur to anyone to think anything of the depictions of Indians in those books. And I think that’s deeply unfortunate and it shows just how much work we had to do with regards to recognizing the racism of those books.”

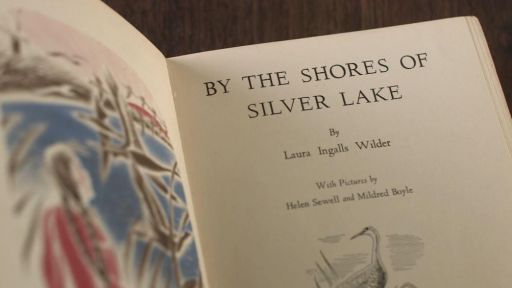

The collection of eight young adult books, which have been read by millions and shared among generations of families around the world, contain several dehumanizing descriptions of Native and Black characters. In one passage in “Little House on the Prairie,” Wilder wrote, “There were no people; only Indians lived there,” while in another, one of the characters, Pa, says, “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” In “Little Town on the Prairie,” Pa appears in a minstrel show and sings a racist song — an anecdote accompanied by an illustration of the characters in blackface.

“There’s a passage in which Laura is fascinated by an Indian baby’s very dark eyes,” recalled children’s author Linda Sue Park who grew up reading the “Little House” books. “I had very dark eyes. So in my childhood mind, when Ma said horrible things about Native Americans, it felt like she was saying horrible things about me.”

“I was hurt by those books, and that took me fifty years to reconcile,” said Park. “Because the books that we love as children, they’re part of us. Right? They’re so much a part of our identity.”

In some instances, racist passages in the “Little House” series were amended in newer editions by book sellers. The ongoing controversy also prompted the American Library Association to rename its Laura Ingalls Wilder Lifetime Achievement Award to the Children’s Literature Legacy Award in 2018.

But some maintain that removing the most disturbing references or calling to ban the books entirely won’t mitigate the problem of pervasive racism and America’s inability to reckon with its own white revisionist history.

But some maintain that removing the most disturbing references or calling to ban the books entirely won’t mitigate the problem of pervasive racism and America’s inability to reckon with its own white revisionist history.

“I know some colleagues have said that they wish those scenes would be cut from new versions of the book. I don’t agree with that,” said Wilder biographer Pamela Smith Hill. “It’s very disturbing, but it is part of our history, and if we don’t talk about these issues honestly with our children we are jeopardizing their future and the future of our country.”

Gay, who has previously written about how the “Little House” books shaped her life from the time she was a young girl in Nebraska, remembers the books as engaging, beautifully written and charming, despite their damaging portrayals of Native and Black characters.

“I can remember details from those books, literally, f– almost 40 years later,” she said. “I still remember the book the first time I read it clear as day — and I can’t say that for books I read last week.

“The books just have to be taught in context, and the proper context, not revisionist context.”