Considered one the most quintessential American artists of the 20th century, Edward Hopper created canvases that compel audiences to inhabit a moment in time, cultivating scenes that are both familiar and introspective.

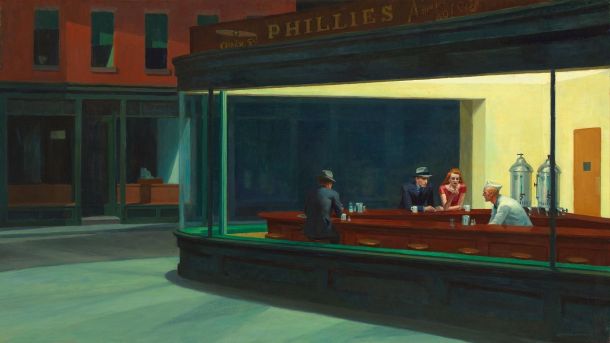

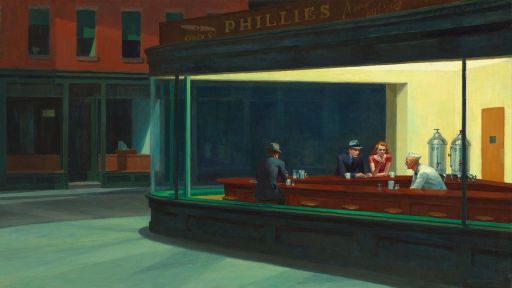

In essence, the imagery encourages its audiences to believe that the works convey how the landscape looked and how it felt to experience them in the 1930s and 40s. This is certainly one reason that Edward Hopper’s painting, “Nighthawks,” remains popular. Completed in 1942, the painting features individuals occupying a quiet diner as they receive service from a lone, uniformed worker. A bright fluorescent glow highlights their still presence as the viewer, positioned outside of the establishment, acts as a witness and curious observer kept at a calculated distance. The identity of the figures, the purpose of their gathering, and the location of the diner remain unknown. What we do know, however, is that Hopper presents an insular environment, in which identity remains unchallenged during a visually and socially diverse era.

Many of Hopper’s painting inspire questions, questions raised by the lack of visual information provided in the work. As an urban scene, “Nighthawks” is full of absences. The red and green, tiered building located in the background and the wide walkway curving around the diner suggest a throughway prepared to accommodate groups of passers-by. Additionally, the broad picture window that define the diner’s architecture reminisce popular contemporary city businesses that encourage hurrying residents to look at displayed wares and even watch busy consumers within their interiors.

Yet, Hopper has abandoned the maelstrom of visual material that define American urban spaces by mid-century.

There are no crowds here, no cars, no movement, no activity. The streets are deserted without people or detritus, and the building in the background appears empty and quiet. With city spaces in the 1920s characterized by a liveliness of post-war consumerism and public revelry, and in the 1930s by urban streets transformed by the unemployed and downtrodden into stages of suffering, “Nighthawks” is a barren wasteland. Except for the name of the diner at the top of the painting, readable signage as well as streetlamps, advertisements and decorative facades have been removed. [Editor’s Note: “PHILLIES,” is not the name of the diner, but actually an advertisement for Phillies Cigars.] The sounds of the city have also been stripped away as the absence of current technologies that inevitably blare and honk as part of the urban din have been muted.Like many of Hopper’s paintings, “Nighthawks” is a sanitized, unsentimental representation of urban life. And this sanitizing is furthered by an insistence on social and cultural homogeneity.

Hopper’s works feature a limited range of characters–young women, adult men, working or middle-class backgrounds, [nearly] all systematically painted racially as white. This is a powerful choice for an artist who staged his works in urban spaces, specifically at a time when cityscapes teemed with a diversity of bodies. Immigrants, women, men of all ages, and those across class, national and racial boundaries routinely intermingled as part of a visual kaleidoscope. They defined both the advantages and challenges of city life. Further, the public nature of urban culture in the first decades of the 20th century welcomed a range of residents to see and be seen, to function as both voyeur and spectacle across assigned cultural categories. As Hopper varies little from his pictorial formula, he creates timeless scenes with white bodies and established “types.” Importantly, these figures do not simply inhabit spaces. Their occupation and prominence offer a stable vision of whiteness and the American landscape. They are eternal and unchanging, and a consistent part of Hopper’s vision of the cityscape.

With these cultural and visual absences, why have “Nighthawks” and Edward Hopper captured the attention of so many audiences? Why is it both familiar and introspective?

Instead, we are encouraged to insert our own narratives, provide backstories for the characters, and recall personal urban environments to fill in the painting’s “gaps.” The painting’s familiarity and thoughtfulness to audiences is, in fact, generated by its mystery or lack of information, and it is viewers’ willingness to assert their own experiences and reflections into the pictured scene that encourages emotional and psychological connection. And, without the presence of multicultural bodies, or gestures to bodies not coded as white, audiences are left with a presentation of an uncomplicated and unvaried world. In Hopper’s work, white urban figures populate sparce city spaces, and audiences are left to unravel the mystery of who, how and why.