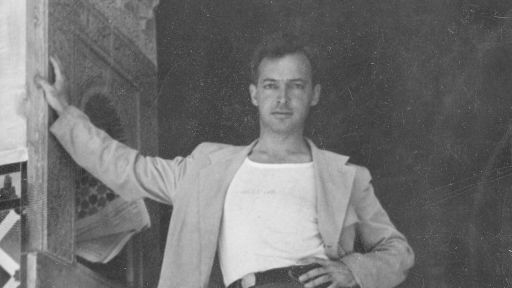

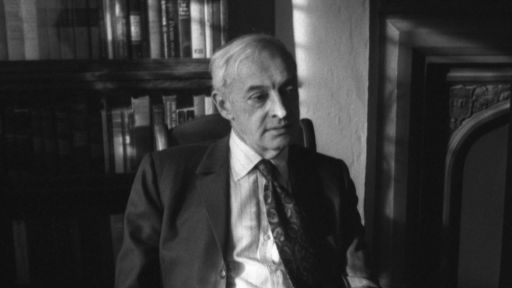

Author Saul Bellow won every award going, including the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Pulitzer Prize, three National Book Awards and the titles Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres, bestowed by the French Republic.

In this essay, biographer Zachary Leader shares his thoughts on Bellow’s body of work, prose and literary influence.

The reasons for reading Saul Bellow go beyond his literary-historical importance. The main reason for reading him is that his novels and stories are so pleasurable, thought-provoking, truthful and funny. Chief among his virtues, to my mind, is his power as an observer. His writing is full of things perfectly seen. Here’s where most people start:

1. “The Adventures of Augie March” (1953)

Much has been made of the style Bellow evolved in his fiction. It first appears in “The Adventures of Augie March” (1953), his third novel, winner of the first of his three National Book Awards. What was new about this style was its range as well as its energy, from high culture to low, the street to the Ivory Tower, hamburgers to Heraclitus. By mixing urban slang, arcane literary and philosophical allusions and Yiddishisms, Bellow was able to portray a galaxy of types previously excluded from high culture, making him, like his hero Augie March, “a Columbus of those near-at-hand.”

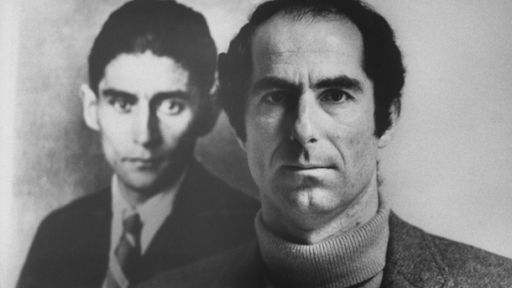

He made no attempt to sacrifice one or other aspect of himself on the grounds of literary fashion or decorum. He was “faithful to what [he] was,” and said, “I lived that way and I tried to write that way.” Hence the liberating appeal of “Augie March” not only to younger Jewish writers like Philip Roth, but to writers from Britain, such as Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie, chafing under the formalities and restrictions of class and culture.

In Asaf Galay’s American Masters film, several writers and critics quote from the famous opening lines of “Augie March”:

“I am an American, Chicago born – Chicago, that sombre city – and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make my record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent. But a man’s character is his fate, says Heraclitus, and in the end there isn’t any way to disguise the nature of the knocks by acoustical work on the door or gloving the knuckles.”

Augie is a Jew but he doesn’t call himself one. He’s open about his Jewishness, and about the Jewishness of his world, but he sees himself first as an American, as did Bellow. Augie’s immigrant world is lovingly detailed, but its inhabitants long for assimilation, the pains and humiliations of which are treated as a source of humor, as well as indignation.

2. “Herzog” (1964)

This is the novel that made Bellow rich and famous, here’s an example of Bellow’s talent for observation – character Moses Herzog, in sweltering Manhattan, comes across a building being knocked down:

“At the corner he paused to watch the work of the wrecking crew. The great metal ball swung at the walls, passed easily through brick, and entered the rooms, the lazy weight browsing on kitchens and parlors. Everything it touched wavered and burst, spilled down. There rose a white tranquil cloud of plaster dust. The afternoon was ending, and in the widening area of demolition was a fire, fed by the wreckage.”

People as well as things are perfectly seen in Bellow’s writing. Here, for example, is a description of a character based on Bellow’s father, a down-at-heels bootlegger on the eve of a crucial, risky deal. In the description, the skin around his eyes and the way he holds himself tell us everything we need to know about his situation, his state of mind, even his fate:

“Something appeared to have got him by the back of the neck and the head and twisted them forward so that he could not recover his normal posture. It was painful to see. The skin was tightened at his eyes so that his eyes would sometimes suggest those of an animal picked up by the scruff of his neck.”

3. “The Old System” and other short stories

Though “Herzog” (1964), “Augie March” and “Seize the Day” (1956) are his best-known novels (the last because it is so short), when asked where to begin, I often say the “Collected Stories” (2001). They show Bellow in top form. In his great story “The Old System,” a businessman, Isaac Braun, a shrewd and daring property developer, also an orthodox Jew, faces a crucial moment in his career – one that involves breaking the law. He borrows $100,000 from the bank and persuades the president of the local WASP country club to sell him some land. In the president’s living room, all mahogany and “pork-pink furnishings,” he is offered a martini:

“Isaac, not a drinker, drank the clear gin. At noon. Like something distilled in outer space. Having no color. He sat there sturdily but felt lost – lost to his people, his family, lost to God, lost in the void of America.”

At the door, the president “did not say he would keep his word.” Two agonizing days follow, the deal goes through, and Isaac becomes a millionaire.

Bellow often spoke of the propositional character of American identity. The fact that “to be an American was neither a territorial nor a linguistic phenomenon, but a concept – a set of ideas.” As he says in an essay:

“Being an American had always been something of an abstract project. You came as an immigrant. You were offered a most reasonable proposition and you said yes to it.”

The contrast with Europe was pointed. When Bellow’s friend Paulo Milano, an Italian literary critic, died, all his obituaries mentioned the fact that he was “of Hebrew birth.” None of them, Bellow noted, “mentioned the fact that his Jewish ancestors had lived in Italy for two millennia.”

The Jewish immigrants in Bellow’s fiction stand out from those in the fiction of earlier Jewish-American novelists. There is no “shtetl stick adapted to the USA,” as Philip Roth put it. “You plugged into Jewish aggression and Jews as businessmen,” Roth told Bellow. “The Jewish success in America is obvious, it’s business . . . The small-time lawyers, the owners of the middle-sized businesses, the conniving and cheating. You were not ashamed of Jewish aggression because you saw it as American aggression . . .It was Chicago aggression.”

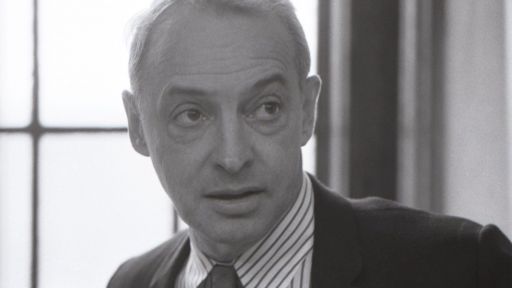

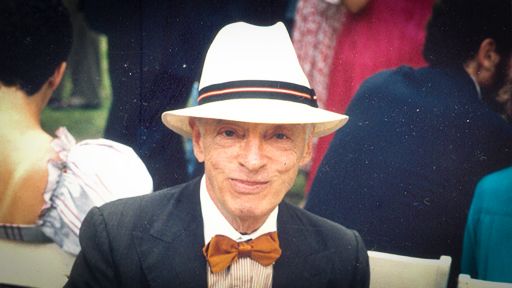

Bellow is not taught much in universities, partly because he writes long (even his short stories are long), partly because he has written and said things that offend. His personality did not help. It was not easy fighting his way to literary success, as his father and brothers did in business. He could be charming and generous, but he was also combative, prickly, not one for turning the other cheek. When criticized, particularly for politically incorrect views, he doubled down. “They say I’m a misogynist,” he told a woman interviewer who quizzed him about his female characters. “I love the adorable creatures,” he answered, an answer meant to incite. Although some would disagree, I would defend Bellow’s fiction against accusations of racism, a charge leveled against his novel “Mr. Sammler’s Planet” (1972)1, winner of the Pulitzer Prize (the less-remarked-upon treatment of women in the novel is harder to defend). The funniest of the novels, my favorite, is “Humboldt’s Gift” (1975), which is wonderful about Chicago.

For much of his life, Bellow’s standing in American Literature could not have been higher or his influence greater. If his books are less read today than in previous decades, all are still in print and his reputation among many fellow novelists is undiminished.

1Editor’s Note: Saul Bellow’s own defense against accusations of racism and misogyny was controversial. You can read his original New York Times Op-Ed here.