By Peter Cooper and Barb Hall

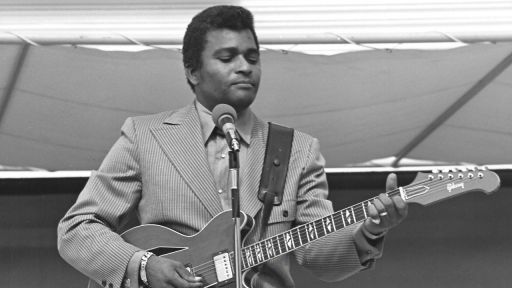

Often referred to as the “Jackie Robinson of Country music,” merging the line between country music and baseball was a seamless transition for Charley Pride.

Raised as less than a citizen in segregated Mississippi, Pride’s buttery voice and steely resolve earned him a place as one of American music’s most impactful artists. He landed in Nashville in 1963, the same year the Tennessee capital was the site of sit-ins and racial violence. Two years later, he was a major label recording artist in the otherwise lily-white country music field, and in short time he became a superstar whose path would lead him to a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and a place in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Pride’s story is a lesson in the ways that art can triumph over prejudice and defeat injustice. It is a window into the complicated story of the American South and its music. It is a tale of black and white, shaded in gray. And for decades, Pride’s hands – which have cradled fine guitars and entertainer of the year trophies – still feel the sharp sting of Mississippi Delta cotton bolls.

Charl Frank Pride was born March 18, 1934, in Sledge, Mississippi. The fourth of eleven children in a sharecropping family, his name was typed “Charley” rather than “Charl” on his birth certificate, and, to his father’s dismay, the “ey” stuck. Born near the end of the Great Depression, his odds of financial success or cultural prominence were minuscule, and yet he was driven by three factors: his love of baseball, his deep love for the Grand Ole Opry music he heard each Saturday evening, and his longing for more than what he saw around him. In Mississippi in the ‘40s, the only thing that couldn’t be segregated was the radio, and Pride listened across color and geography, to the sounds that would lead him from the Delta to a larger, grander world.

At 17, he left home to play baseball — he pitched and played outfield in the Negro American League. By that time, Jackie Robinson had broken Major League Baseball’s color barrier, and Pride hoped to follow in his footsteps to the big leagues. An arm injury decelerated his fastball, and he attempted to develop a knuckleball in order to advance his cause. At the Memphis games, he was both impressed and smitten with baseball fan Rozene Cohran and eventually convinced her to go on a date. The two struck up a fast romance that would result in a 61-plus-year marriage and partnership.

A two-year stint in the Army derailed his baseball career, but he returned to the game upon civilian reentry and racked up experience playing against big leaguers including Ernie Banks and Warren Spahn.

Cut by several organizations, he moved his family to Montana, where he took a job at a lead smelter and played for the East Helena Smelterites semi-pro baseball team. There, he began singing country music at company picnics and in clubs where the music gigs were more satisfying than unloading coal into a 2,400 degree furnace. Life in Montana was mostly free of racial strife, but he knew that if he really wanted to pursue a country music career he needed to return to the South.

Not ready to give up his baseball dreams, he planned his own entry to spring training for the hapless New York Mets. He ordered six Brooks Robinson model bats from the Louisville Slugger Company and had them shipped to the Mets’ Clearwater, Florida spring camp in hopes that Mets manager Casey Stengel would assume he was supposed to be a prospect. But Stengel informed Pride that he wouldn’t be considered for the team. Dejected, he took the bus from Clearwater home to Montana with a fortuitous stop to Nashville, where he pinned his hopes on a country music break.

In Nashville, he was heard by Jack Johnson, who signed him to a management contract and promised to try to get him a recording contract. Pride returned to Montana to await some good news. Two years later, Johnson entered a Nashville bar and saw producer/raconteur “Cowboy” Jack Clement, the rare Music City man crazy enough to consider the idea of a black country singer in 1965. He gave Clement a Pride demo tape, and Clement said, “Get him in here.” Pride did just that, and Clement gave him a tape, telling him that if he’d learn these songs then they could record them in a real studio.

“Five or six days later, Charley came back… and I had a session set up at RCA Studio B, and we went in and did it,” Cowboy said. “I paid for it, and… well, then I had the only Charley Pride record in town. I had this office with these big speakers, and I’d get people in there and play Charley’s record. Loud, man. Like, really loud. I’d play that record and then I’d show ‘em his picture. That was fun.”

Cowboy convinced RCA Nashville chief Chet Atkins that he should sign Pride, and Atkins convinced RCA’s national staff that this idea was reasonable. Two singles sent to disc jockeys without Pride’s publicity photo failed to make much of a dent, but a third, “Just Between You and Me,” became a Top Ten hit, and Pride entered country music’s big time.

This entry was not without difficulty or suspense, as each show was a wild card, with the possibility of danger or violence ever-present. Pride had to negotiate tense relations, some of them with white country stars and some of them with audiences.

“The color issue was always there, hanging around with the unpleasant odor of an old wet dog lying on the doorstep,” he said. “I had to find ways to deal with it.”

One night in Texas, Lone Star hero Willie Nelson walked onstage, planted a kiss on Pride’s mouth, and walked off, blessing the occasion like the funkiest of popes. On the Lawrence Welk Show, Pride was positioned in the camera shot alongside his studio steel guitar player, fellow Mississippi native Lloyd Green, and viewers understood that Black and white musicians were now making country music together. In 1969, Green led Pride’s band through a momentous live show that Clement recorded for RCA, and the resulting album was proof of Pride’s artistic prowess.

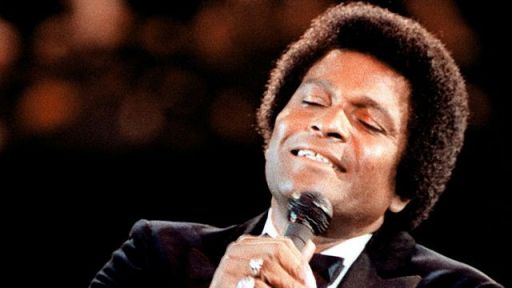

In 1969, Pride scored his first #1 single with “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me),” and he returned to the top spot twelve more times over the next five years. His “Did You Think to Pray” won a 1971 Grammy Award, and that same year he was named the Country Music Association’s Top Male Vocalist and Entertainer of the Year.

Although he appeared confident and unflappable onstage, Pride quietly battled symptoms of bi-polar disorder. His wild swings of mood and emotion were soon mediated by medication and by his steadfast wife, Rozene, who helped calm and center him through a twenty-year stint in which he sold more records than any other RCA artist except Elvis Presley.

Charley Pride was a star of the Grand Ole Opry, a show that was named in 1927, by a WSM radio announcer George D. Hay, who promised the audience that they would no longer be hearing the “Opera” they were accustomed to. Now they would hear “The Grand Ole Opry.” Then he turned the microphone over to an African American harmonica wizard named DeFord Bailey. After fourteen years as an Opry star, Bailey was let go and no Black country stars emerged throughout the ‘40s or ‘50s. Genius of soul Ray Charles scored big in 1962 with his “Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music” album, and Nashville studios often housed integrated sessions, but country charts and package shows featured white artists singing for white audiences.

Charley soon offered up hit song, “I’m Just Me.” The lyrics included “…I was born to be exactly what you see.” By the time “I’m Just Me” hit the radio in 1971, that statement seemed evident, even obvious. That was not the case in 1963, when Pride, wounded by his dismissal from the New York Mets’ camp without ever setting foot on the field took a Greyhound bus to a Nashville that was in the midst of unprecedented racial strife. He walked without an escort or an instrument from the bus station to Music Row, entered the Cedarwood Publishing building and asked for an audition. Music manager Jack Johnson listened as he sang a Ray Price song and a Hank Williams number, then said, “Pretty good. Now sing one in your natural voice.”

“What do you mean?” Pride asked. “This is my natural voice.”

During a time when the South was a tinderbox, and when Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcom X were being gunned down, he stood with white musicians, singing brilliantly and making a statement about unity and commonality of experience that was apolitical and radical.

His story bridges the intersection of country music and civil rights movement. Pride matters because he is the embodiment of the movement to a segment of white culture that wasn’t knowingly touched by the movement at the time. Zooming in at the intersections, overlaying Charley’s story against the timeline of country music and the timeline of the civil rights movement in America spotlights a remarkable and unconventional story. Country music, a lyrical soundtrack of plain folks, speaks the language of everyday people. Music has a proven ability to blur the divisive lines. Charley Pride’s story is not one of a typical civil activist but rather a life lived as though his civil rights deficit would not interfere.

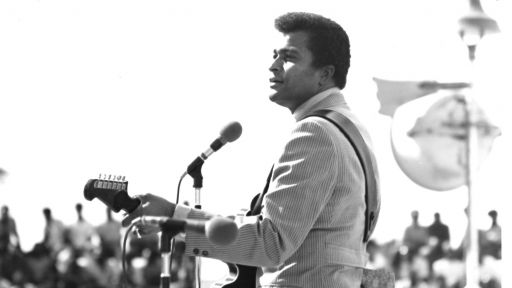

“I was born in Sledge, Mississippi and was raised there until I was about 17 years old,” He told the audience on one of country’s greatest live albums, “Charley Pride—In Person.” “I get a lot of questions… ‘Charley, how’d you get into country music, and why you don’t sound like you’re supposed to sound?’ It is a little unique, I admit. But I been singing country music since I was about five years old, and listening to the Grand Ole Opry.”

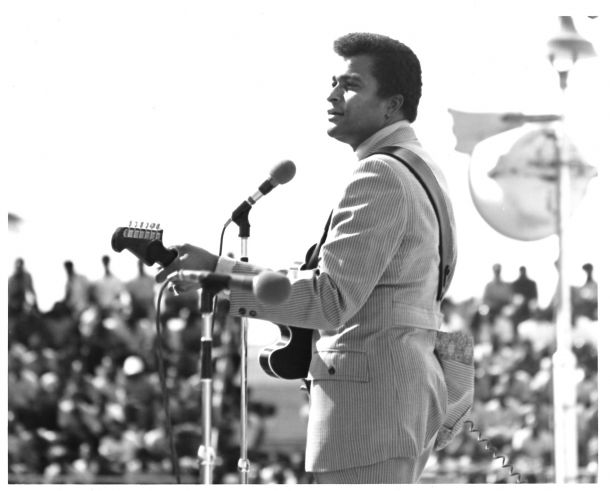

Onstage, he frequently referred to his “permanent tan” and his “pigmentation situation,” slyly nodding to the elephant in every room while simultaneously shifting hearts and minds towards respect and understanding. Country music offers poetry for common people, with listeners often responding, “He’s singing exactly the way I feel.” That such feelings could be voiced by a black man and ricochet across color lines was something young rock and pop audiences had understood since the ascent of Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, the Drifters, and others. But every Southern Pride show offered an integrated stage in a segregated town. Thus, the filmed Pride performances contain an inherent tension and release that remains fascinating and compelling all these years down the line.

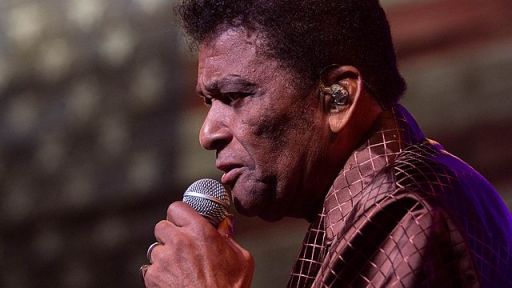

Pride winds up as an enduring legend of American music, with an unassailable artistic catalog, an ownership stake in the Texas Rangers, and a spot in the Country Music Hall of Fame alongside the heroes who sang through his childhood, through radio speakers in the Mississippi Delta. He stands as a symbol of hope and an example of the ways music can influence societal change.

Who is Charley Pride? The inescapable conclusion is….“I’m Just Me”