Sariel Friedman explores the evolving construction of the American dream, including its depictions in the novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gish Gen, Saul Bellow and others.

Written as part of the American Masters Digital Archive project, this essay draws on original interviews conducted for “Novel Reflections on the American Dream,” including extensive conversations with writers Gloria Naylor, Andrew Delbanco and Maureen Howard.

What comes to mind when you think about the American dream?

Huddled masses disembarking from a boat? Your ancestors stepping out of a covered wagon? Or is it a modest suburban house with a front lawn and a little dog? A mother, a father, and a boy and a girl grinning ear to ear next to a newly polished Kodachrome red station wagon?

Fiction is a reflection of the social and political conditions of the time and the concept of the American dream weaves its way through the stories we tell. It is reflected through the universal characters found in Theodore Dreiser’s “Sister Carrie” and Edith Wharton’s “House of Mirth;” in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” and John Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath;” in Ann Petry’s “The Street,” in Gish Gen’s “Typical American” and in Saul Bellow’s “Seize the Day.”

The answers are varied, but the language is universal:

Upward mobility, independence, hard work; a chance to jump into the melting pot, hearts light and spirits high with the promise of freedom and reinvention. The dream is what binds us together and moves us forward, a secular religion fit with sacred texts and a list of values articulated by Benjamin Franklin—“the early bird gets the worm,” “early to bed, early to rise,” “no pains without gains.” With enough faith and belief in hard work and ambition, anyone can be saved.

All of these characters possess the same faith in the American dream, whether it’s John Steinbeck’s Joad family in the throes of the Great Depression in “The Grapes of Wrath” or Saul Bellow’s Tommy Wilhelm reckoning with his unhappiness in “Seize the Day.”

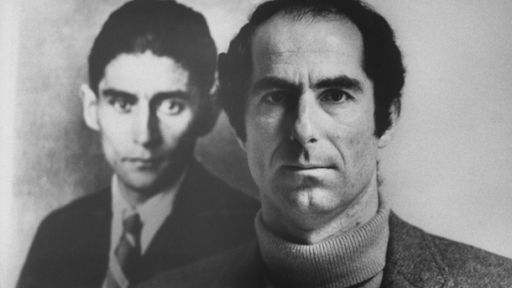

As depicted in “Seize the Day,” the generational divide is explored in the dynamic between father and son. Professor of English and African-American literature at UCLA, Richard Yarborough, shared his thoughts on Saul Bellow’s portrayal of “The Dream” and its evolution through generations:

“[The dream] is such a central part of the American fabric of our culture that we continue to see new participants in the Americanization process of people who are coming to the United States. . . And we find that they seem to embody the same faith in possibility that marked 1850 or even March 1750. I think that this is this must be a core component of what it means to be an American citizen, that you have to some way define your relationship to that ideal. . . I personally think that that the dream is pervasive enough that it is renewed with each generation.”

The writers of these American novels test its limits, lay it bare in all of its seductive richness and appeal; and then run it right into the wall.

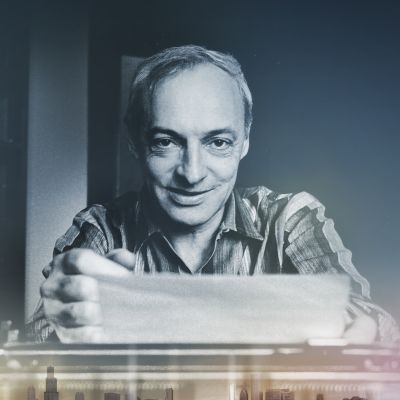

A re-creation of Tommy Wilhem acknowledging the transience of life in Saul Bellow’s “Seize the Day.”

But in each of these stories, as hopeless and tragic as they are, all end with a small kernel of hope. Redemption is found not in the American dream, but in the characters themselves. It comes in spiritual rather than physical form. Our attention is turned to the recognition of our own humanity and the humanity of others. Each of the novelists in “Novel Reflections on the American Dream” suggest a reinvestment of all of that faith and idealism in the human spirit. We learn that until a deeper essence or soul is found, success is not possible.

The demons that these characters wrestle with change, but the pillars of the American dream are static. Throughout history, these people change—the religion they practice, the color of their skin, the language that they speak, but people are still struggling to make the same dream their reality.

“The past is no good to us. The future is full of anxiety. Only the present is real—the here-and-now. Seize the day.” —Saul Bellow, “Seize the Day”

Even today, we are still chasing the same elusive ideals. It seems that the glimmer of hope that we hold out is slowly fading. We must look to the next generation for a new reflection on the American dream, a novel that can reinvigorate our faith in ourselves, our families, and our communities. What text reflects our contemporary reflection of the American dream?