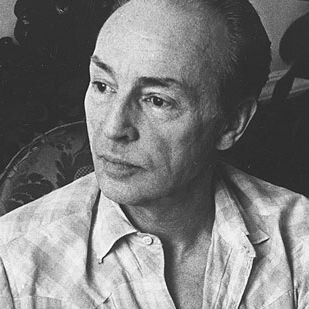

Beyond classic musicals like “The Sound of Music” and “South Pacific,” writer Laurence Maslon breaks down the unparalleled career and influence of composer Richard Rodgers.

Among some notes for an unfinished novel, F. Scott Fitzgerald famously (or infamously) observed, “There are no second acts in American lives.” Using only 88 keys and a bottomless supply of genius, composer Richard Rodgers proved Fitzgerald dead wrong, living through a three act career and providing us with a fourth act in posterity.

Rodgers’s first act as a theatrical composer began in 1919 as a collaboration with lyricist Lorenz Hart that lasted into World War II. Their witty songs and melancholy ballads made them the most popular and adventuresome songwriting team on Broadway and (briefly) in Hollywood. Among their three dozen projects were such triumphs as “Babes in Arms,” “The Boys from Syracuse” and “Pal Joey.” Rodgers and Hart also gave the world such immortal songs as “Where or When,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Falling in Love with Love” and “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered.”

His second act was a partnership with lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, who also wrote the complex and moving narratives (“books”) for their shows. Beginning in 1943, they wrote nine shows together (and one television score and one film score), full-throttled musical stories that captured the imagination of the American public in the post-war years. With shows such as “Oklahoma!,” “Carousel,” “South Pacific” and “The Sound of Music,” Rodgers and Hammerstein created not only record-breaking commercial successes, but resonant and enduring tales of character, moral values and emotional aspiration.

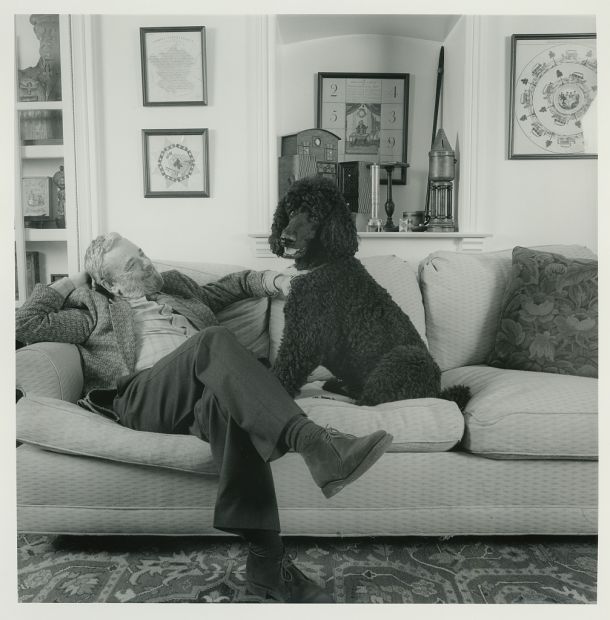

When Hammerstein died in 1960, Rodgers might have retired, but as he said, “Well, I’m on a new road—I have to move forward, whether it’s with Joe Blow or someone else.” He did so initially by writing his own lyrics and winning a Tony Award at the age of 60 for his score to “No Strings,” a 1962 hit. He worked either on his own or with other collaborators for two more decades. In December 1979, Broadway produced the first full-scale revival of “Oklahoma!”—Rodgers died 11 days later, 48 hours shy of the 1980s.

What follows are some observations about the magnitude of his artistry and their ongoing influence on American culture:

Making—and breaking—records

The 1949 original cast album of “South Pacific” was released at about the same time as record manufacturers and producers were trying to hook the public on a new technology: the 33 1/3 rpm Long Playing record. The Rodgers score and the new consumer product were made for each other and the Columbia Broadway cast album was number one for 63 weeks—an industry record at the time by a monumental margin. Only one other album in the next ten years came close to matching that—the 1958 movie soundtrack for “South Pacific;” the RCA recording was number one for 31 weeks.

The original cast album of “The Sound of Music” with Mary Martin was released in December of 1959 and hit sixteen weeks at number one—that is, “number one” of all popular music in America. The cast album would stay on the charts for 276 weeks; from March of 1965 to November of that year, it overlapped with the movie soundtrack of “The Sound of Music.” That recording hit number one for two weeks in November 1965 and would remain on the charts for 233 weeks until late 1969. This means that, by one reckoning, the most popular and enduring music in America throughout the 1960s was the score to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The Sound of Music.”

Richard Rodgers had multiple key creative partners

Many people think that Rodgers wrote “Oklahoma!” with Oscar Hammerstein after Lorenz Hart died; far from it. When approached with the project in 1942, Hart was never interested in musicalizing the source material and gave Rodgers his blessing to work with Hammerstein instead. Hart even attended the opening night on April 1, 1943 and congratulated Rodgers enthusiastically. They took up one more project together in the hopes of keeping the collaboration going, a revised version of their 1927 hit, “A Connecticut Yankee.” It was playing on Broadway, on the other side of Eighth Avenue from “Oklahoma!” when Hart died on November 22, 1943.

The influence of “The Sound of Music” on jazz

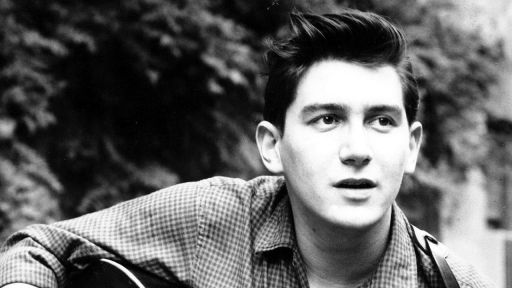

In the middle of 1960, the famed jazz saxophonist John Coltrane had left the Miles Davis Quintet and formed his own quartet. Apparently, a song plugger—no one quite remembers who or where from—gave the sheet music from “The Sound of Music” to Coltrane. Thinking it was probably a good idea to render some popular standards, Coltrane included “My Favorite Things” on his third album for Atlantic, entitled “My Favorite Things,” released in March of 1961. Coltrane brilliantly rethought the melody as a nearly 14-minute hypnotic roundelay, performed on soprano sax in 6/8 time. Eventually cut down and released as a single, the song became Coltrane’s most requested number and he experimented with it relentlessly over the next six years of his tragically brief life. When asked in 2011 if the Quartet ever went to see the Broadway version of “The Sound of Music,” its pianist, McCoy Tyner, laughed and said, “That’s unimaginable.”

Dream ballets

The three greatest stage choreographers of the middle of the twentieth century were George Balanchine, Agnes de Mille and Jerome Robbins. Rodgers was the only composer to collaborate with each of them—dance was always central to Rodgers’s sense of musical narrative. By extension, one could also include Bob Fosse in the list—he performed on-stage in a 1962 New York revival of “Pal Joey” as the lead character, Joey Evans.

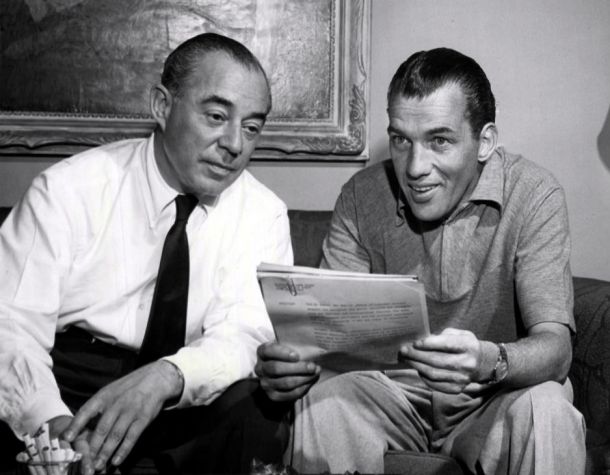

Side-by-side with Stephen Sondheim

If one could readily accede that Rodgers was the most revered Broadway songwriter for the first half of the twentieth century, Stephen Sondheim equally qualifies for the second half. Before Rodgers would pass the baton on to Sondheim, they were briefly teammates on the same project: the musical “Do I Hear a Waltz?,” which ran for 220 performances during the 1964-65 season on Broadway. Rodgers had known Sondheim since the 1940s when Sondheim was a protégé (and neighbor) of Oscar Hammerstein’s. Hammerstein had asked Sondheim once he had passed away to consider working with Rodgers; likewise, Hammerstein suggested to Rodgers that he work with a younger lyricist—Sondheim, in fact.

The two men approached each other warily. Sondheim thought Rodgers could be old-fashioned and rude, while Rodgers thought Sondheim was cynical and disrespectful. However, although “Do I Hear a Waltz?” was not a major hit, the score possesses moments of surpassing beauty with Rodgers’s melodies and Sondheim’s words blended together far more harmoniously than the collaborators did in rehearsal. That show would be the last time Sondheim would write significant lyrics for another composer, and although Rodgers would occasionally disparage Sondheim’s melodic ideas, he also praised Sondheim’s own shows and even invested money in them.

Did I write a waltz?

Rodgers was so prolific and popular throughout most of the twentieth century that practically every pop singer from 1925 to 1975 sang at least a half-dozen of his songs. Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, Bing Crosby, Jo Stafford and Doris Day—among many others—each had hit singles and popular albums singing his tunes. Ella Fitzgerald released a groundbreaking two-album Rodgers and Hart songbook on Verve, covering 34 of their tunes in 1952, and as late as 1967, Diana Ross and the Supremes also tried their hands at a two-LP set of Rodgers and Hart tunes for Motown.

Singer Peggy Lee had a big hit in 1952 with “Lover,” a song written twenty years earlier for the film “Love Me Tonight.” Her version hit number three in the pop charts, which must have made Rodgers happy, but the arranger transformed the song from a waltz tempo into a Latin version with bongo drums—which didn’t. Lee wrote in in her autobiography that Rodgers “was usually very strict about how his songs were to be performed. All of us respected him so highly that we were happy to follow his orders. A bit later on, when I did ‘Lover,’ apparently I forgot that.” Supposedly Rodgers made a lot of noise in public over his displeasure, even writing an article for a New York newspaper: “I must admit that when a tune is new and offered to the public for the first time, I am inclined to protect it with my heart, soul and body as if it were a new baby . . . I suppose this recording [of ‘Lover’] is about as far as you can go in the way of distortion and still have the nerve to use the title.” Although his precise direction over his tunes became legendary, he must have made up with Lee at some point; she subsequently appeared in several television tributes to his work.

Of course, Rodgers wrote songs for some of the most admired and monumental stars of the Broadway stage—Alfred Drake, Mary Martin, Gertrude Lawrence—but the list of other stars and personalities who originated Rodgers melodies on stage or screen is astonishing in its variety and scope: Al Jolson, Jeanette MacDonald, Jimmy Durante, George M, Cohan, Gene Kelly, Desi Arnaz, Dick Haymes, Yul Brynner, Eddie Albert, Ray Bolger, Julie Andrews, Diahann Carroll, Sergio Franchi, Danny Kaye, Madeline Kahn, Nöel Coward, Keye Luke, Glenn Close and Liv Ullmann.

Richard Rodgers’ songs have come to represent these places

The title number from “Oklahoma!” was adopted as the state song in 1953. “Edelweiss” from “The Sound of Music,” however, is neither an Austrian folk song nor the Austrian national anthem, although someone in the Reagan White House apparently didn’t get the memo: Rodgers’s tune was used to introduce the Austrian chancellor during a state function in 1984.

Live from New York

“The Ed Sullivan Show” was the leading variety show on television for four decades, commanding national audiences every Sunday night from 1948 to 1970. On his very first show, Sullivan hosted Rodgers and Hammerstein, who talked about their upcoming musical “South Pacific” (that episode, sadly lost to history, also featured performances by Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis). Sullivan, who had also been a Broadway columnist, was an immense fan of Rodgers. Rodgers was asked to appear on the Sullivan show more times than any other non-performer—a total of 17 appearances, including four separate hour-long tributes.

A firebrand at branding

Although Irving Berlin had pioneered the way for songwriters to take control over the publishing rights to their material back in 1917, it was Rodgers, in partnership with Oscar Hammerstein, who had the visionary idea of maintaining complete creative control of his work. Creative control was important to Rodgers; when he made his Broadway debut—still in his teens!—with a show called “Poor Little Ritz Girl,” he attended opening night with his parents only to open his program and discover that while he was away from rehearsals (as a summer camp counselor, no less), half of his score had been replaced. “Fifty years later,” he wrote in his 1975 memoir, “I still feel the bitter disappointment and depression of that evening.”

As soon as he had the clout to do so, Rodgers produced or co-produced his own stage musicals—he and Hammerstein were even executive producers of the film versions of “Oklahoma!” and “South Pacific,” a level of creative control rarely, if ever, conceded to Broadway songwriters.

In 1944, following the success of “Oklahoma!’s” debut on Broadway, Rodgers and Hammerstein formed their own publishing firm, Williamson Music. The name was a rare bit of whimsy on Rodgers’s part—both he and Hammerstein had fathers named “William.” To this day, Williamson Music is a powerhouse; in addition to Rodgers and Hammerstein, it represents the music publishing rights to artists such as Stephen Schwartz and Lin-Manuel Miranda.

You still hear Richard Rodgers’ music everywhere you turn

In the last ten years alone, Rodgers’s music has been used in nearly 50 movies, television shows and commercials, including “Bridge of Spies,” “The Wolf of Wall Street,” “Watchmen,” “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” and “The Simpsons.” In the 2021 film “Being the Ricardos,” an entire scene is recreated from the film version of his 1939 stage musical, “Too Many Girls,” written with Lorenz Hart and featuring Javier Bardem as Desi Arnaz.

In 2022, there is a national touring company of an acclaimed revival of “Oklahoma!” as well as a West End revival of “The King and I.” A Broadway revival of “Pal Joey” is planned for 2023, as is a television series suggested by “Oklahoma!”

When asked about his place in posterity, Richard Rodgers said, “If someone wants to sing something of mine 30 years from now, no one will be happier than my dead body.”