“No romantic novel ever written in

America, by man or woman, is one

half so beautiful as MY ANTONIA.”

— H. L. Mencken

In the mid-1970s, not long after I had moved from New York City to Lemmon, South Dakota, I attended a 90th birthday party for a woman who had been one of the original homesteaders in the area, having immigrated from Sweden with her parents in 1909. The Lutheran church basement was decorated with crepe-paper streamers, and one table held family photographs — color snapshots of the great-grandchildren, wedding photographs from the 1950s, daguerreotypes of stern-faced ancestors in the Old Country. Most of the woman’s children were in attendance; I knew the ones who ranched in the area, but not those who had moved on to Oregon, Washington, California. In the course of our conversation, my husband asked her how many children she’d had, and the woman laughed nervously and said, “Oh, dear, I don’t remember. Some died so young. Sixteen, maybe … 14. Eleven lived.”

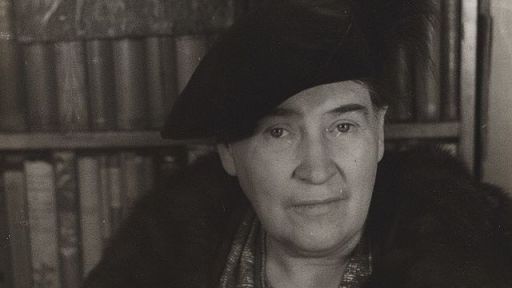

Such stories seem anachronistic in present-day America, but the monumental rigors of pioneer life are still a vivid memory for many on the Plains. Willa Cather’s MY ANTONIA is about the hardy people who risked their lives and fortunes in a harsh new land; Cather had the great good fortune to have lived among the first generation of white settlers in 1880s Nebraska, and she gives witness to their time and place in such a way that American literature will never forget them. MY ANTONIA, following O PIONEERS! (1913) and THE SONG OF THE LARK (1915), completes the trilogy of Cather’s best-known Nebraska novels. Critic H. L. Mencken thought MY ANTONIA to be the most accomplished and, reviewing it in 1919, shortly after it was published, he wrote, “Her style has lost self-consciousness; her feeling for form has become instinctive. And she has got such a grip upon her materials. … I know of no novel that makes the remote folk of the Western prairies more real … and I know of none that makes them seem better worth knowing.”

It was risky, in the early part of this century, to presume to write fiction about ordinary, rough-hewn people engaged in the rigors of dry land farming in frontier Nebraska. The prevailing literary style was for overrefined, predictable, plot-driven novels with characters who held fast to European pretensions and standards of gentility. Along with writers such as Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis, Willa Cather was seen by some contemporary critics as an answered prayer. Writing about O PIONEERS!, which had established Cather’s national reputation when it appeared in 1913, one critic stated, “Here at last is an American novel, redolent of the Western prairies.”

Louise Bogan, who termed Cather an American classic in THE NEW YORKER, treasured the authority of Cather’s voice, her having “learned all there was to know about the prairie, including how to kill rattlesnakes and how prairie dogs built their towns.” Above all, Bogan praised Cather for not being one of those “writers of fiction who compromised with their talents and their material in order to amuse or soothe an American business culture.” Refreshed by Cather’s evocation of pioneer life, Bogan said admiringly that Cather “used her powers … in practicing fiction as one of the fine arts.”

Cather herself complained in a 1922 essay that “the novel, for a long while, has been over-furnished.” Intent on telling the truths of a particular time and place, she made her own prose as spare as the land about which she was writing, and became a pioneer in American fiction. While Europe figures in MY ANTONIA as a lost Eden, or a repository of terrible secrets that haunts the immigrants in their new land, the novel is solidly grounded in America, its language the uncluttered idiom of the farmers and townspeople of Webster County, Nebraska. For example, young rural women in Boston or New York who moved into town to earn wages to help support their families on the farms were commonly called “servants.” Cather, however, knew that in Nebraska they were called “hired girls,” and that’s what she calls them in MY ANTONIA.

Cather’s Nebraska novels vibrate not only with the spoken language of ordinary people but also with the visual images that help a reader truly to see a place. In MY ANTONIA Cather moves smoothly and spectacularly from the small detail to an exalted vision of the landscape and its possibilities. Not long after 10-year-old Jim Burden arrives in Nebraska, having been orphaned in Virginia, he mulls over his grandmother’s solemn instruction never to go to the garden without a stick for clubbing rattlesnakes. Then he muses: “Alone, I should never have found the garden. … I wanted to walk straight on through the red grass and over the edge of the world, which could not be very far away … if one went a little farther there would be only sun and sky, and one would float off into them, like the tawny hawks which sailed over our heads making slow shadows on the grass.”

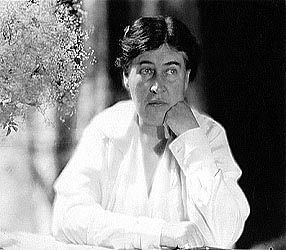

Willa Cather was born on December 7, 1873, near the town of Winchester, Virginia, in the North Neck region of the state, where her ancestors had farmed since the late 18th century. She was the first of seven children. Cather was nine when her family moved to Nebraska, following her father’s parents and his brother, who had emigrated to the frontier during the 1870s. Cather’s family left behind a large and prosperous farm, a house that Cather remembered as roomy and cheerful, and, of course, the lush foliage of Virginia. Her family settled on a farm near Red Cloud, Nebraska, which had been founded in 1870, and by the time Willa Cather arrived, it had a population of about 1,000, a school, and a small opera house.

The near-treeless countryside could not have been less like Virginia, and the drastic change took a toll on the young Willa Cather. In a newspaper interview following the publication of O PIONEERS!, Cather said that the new landscape had evoked a sense of “erasure of personality.” In MY ANTONIA, Jim Burden says of his first glimpse of Nebraska, “There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.” During the 20-mile trip by horse-drawn wagon from town to his grandparents’ farm, Jim looks out at the starry night and says of his deceased parents, “I had left even their spirits behind me. The wagon jolted on, carrying me I knew not where. … Between that earth and sky I felt erased, blotted out.”

Jim Burden serves Cather well as a narrator of the land. As he is settling in with his grandparents, he notes with wonder that theirs is the only wooden house for miles around, and that their neighbors live in houses made of sod. His sense of being obliterated by the landscape remains strong: “Everywhere, as far as the eye could reach, there was nothing but rough, shaggy red grass, most if it as tall as I.” But he begins to find beauty in the sea of grass, its red “the colour of wine-stains, or of certain seaweeds when they are first washed up. And there was so much motion in it; the whole country seemed, somehow, to be running.” In an elegant phrase that became Cather’s epitaph — it is etched on her tombstone — Burden comes to accept the power of the land over him, asserting, “That is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.”

Cather said in a 1921 interview that the years from eight to 15were particularly formative in any writer’s life; clearly, for her, it was the experience of moving to Nebraska and absorbing its pioneer culture that first inspired her as a writer and gave us the most beloved of her novels. At the age of 11 Cather obtained employment delivering mail to the farms around Red Cloud, which gave her unparalleled access to the talk and the lives of her immigrant neighbors. The knowledge she gained about them, however, set her apart from the other English-speaking settlers. In a 1923 essay entitled “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle,” she says of her own people that they were kind to their neighbors from Europe but also “provincial and utterly without curiosity” about the Old World cultures from which these people had come. MY ANTONIA reveals the subtle ironies of a social milieu in which, as noted in Doris Grumbach’s 1988 foreword to this novel, the Czechs, Swedes, and Norwegians “were looked down upon for their poverty but were lonely for a culture which was, in many cases, richer than their American neighbors’.”

Antonia Shimerda’s father is a tragic case in point. A cultured man, a violinist, he cannot bear the weight of the hardships he encounters in Nebraska — living with his family in a crude dugout and taking turns wearing the one overcoat they own. Lacking the skills to manage a farm, he clings pathetically to his Old World wardrobe, emerging from the earthen dugout in a coat and “a knitted grey vest, and, instead of a collar, a silk scarf of a dark bronze-green, carefully crossed and held together by a red coral pin.” Mr. Shimerda was a common type among Plains homesteaders. My own great-grandfather Heyward, a proper Englishman, once refused to evacuate a South Dakota parsonage that was on fire until he was fully dressed.

Jim Burden notes that Antonia is the only one of the Shimerda family “who could rouse the old man from the torpor in which he seemed to live.” When Jim examines a gun brought over from the Old Country, he finds Mr. Shimerda looking at him with “his faraway look that always made me feel as if I were down at the bottom of a well.” Jim senses that his grandmother, too, is “so often thinking of things that were far away.” This homesickness is an important link between the native-born American homesteaders and the more recent immigrants; it helps them bridge their differences. When Shimerda, overcome by emotion, suddenly kneels and prays before the Burdens’ Christmas tree, Jim’s grandfather somewhat nervously bows his head, “thus Protestantizing the atmosphere.” After Shimerda has taken his leave, thanking the Burdens and blessing Jim with the sign of the cross, Jim’s grandfather tells him simply, “ŒThe prayers of all good people are good.'”

This scene underscores a reality of frontier existence: circumstances of deprivation and isolation often deprive prejudice of the ignorance and distrust that it needs in order to thrive. By the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was active on the Plains, preaching a virulent anti-Catholicism, but in both O PIONEERS! and MY ANTONIA, Cather offers us a glimpse of a more innocent time. Even now, in the remotest places on the Plains, places that the larger society does not notice or care about, I’ve found that country people can often bridge cultural gaps with ease; they know that theological or ideological distinctions matter far less than the needs of the people at hand.

In writing about a novel such as MY ANTONIA, which has long been considered a classic of American literature, I am temped to play the devil’s advocate and ask a simple question, one that any 15-year-old assigned to read the novel might ask: Why read it NOW? What possible relevance can it have for life in urban, postmodern America? One can point, of course, to the many small delights of observation that give the book its rich texture, the “nimble air” of spring that releases the settlers from the fierce grip of winter, or Burden’s observation that on a quiet night “it seemed as if we could hear the corn growing … under the stars one caught a faint crackling … where the feathered stalks stood so juicy and green.” There are also people we recognize: the suspicious Mrs. Shimerda, unable to recognize that what she considers her peasant canniness is a self-defeating form of paranoia; the pompous and cruel Wick Cutter, “full of moral maxims for boys,” who rapes his hired girls; and the hateful Mrs. Cutter, whom Cather describes, memorably, as having a face “the very colour and shape of anger.”

But MY ANTONIA also holds an important place in American immigrant fiction; it taps into a communal sense of America as an admixture of rich heritages. Many people now alive, my own family included, share the story of the English, Scottish, and Irish immigrants who came to the Great Plains by way of New England or Virginia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I suspect that Willa Cather would be fascinated by contemporary novels about more recent immigrants by the Asian-American and Hispanic writers who are currently enriching American literature. No doubt some of these writers have learned much from Cather about what it means, as a novelist, to have fidelity to a time and a place. MY ANTONIA concerns, as do many of these recent books, coming of age in a new place and culture; it also explores childhood affections, dreams once held dear, in the light of an adult awareness of displacement. Cather herself epitomizes an all too American displacement; her best writing years, including the period in which she wrote her first three Nebraska novels, were spent in New York City, where she had gone in 1906 to work as an associate editor at MCCLURE’S, one of the most popular magazines of the day.

In many ways the world of MY ANTONIA is still with us, a neglected but significant part of America. While Cather witnessed the drastic changes that were occurring on the Plains in the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, from the first to the second and third generations of immigrants, a writer now living on the Plains would note another kind of change: like most small towns in the region, Cather’s Red Cloud, Nebraska, has been losing population ever since she wrote about it. Its population surged to nearly 2,000 in the 1890s, and is down to some 1,131 people today.

In a prophetic 1923 essay on Nebraska, Willa Cather noted with unease that the children of the immigrants, the second generation to farm the Plains, “were reared amid hardships, and it is perhaps natural that they should be very much interested in material comfort, in buying whatever is expensive and ugly.” She saw rural Nebraskans succumbing to the enticements of manufacture, the beginnings of a consumer society, and commented, “The generation now in the driver’s seat hates to make anything, wants to live and die in an automobile, scudding past those acres where the old men used to follow the long cornrows up and down. They want to buy everything ready-made: clothes, food, education, music, pleasure.” She wonders if the generations of the future will be fooled. Will they believe, she asks, “that to live easily is to live happily?” A relevant question for any thoughtful person in a consumer society, but one that has special resonance for those who still farm and ranch on the Great Plains and ponder the transition from families engaged in agriculture to corporations practicing agribusiness.

The cities of America contain a Great Plains diaspora, full of people who, like Jim Burden, left the small towns and farms of their youth for an easier life, who felt that they had to leave in order to make their way in the world. Like him, they are haunted by the past and by the painful ambiguities of their relationships with the friends and relatives who remained on the land. A lawyer in Fargo, North Dakota, the first in his family to graduate from college, told me recently that his family back in western North Dakota was enormously proud of his success, and would never forgive him for leaving. I picture this diaspora as people distractedly watching CNN in city apartments, but containing deep within themselves a vision of the long, “sunflower-bordered roads” in farm country that had seemed to Jim Burden “the roads to freedom.”

The doctrinaire socialist and Marxist critics of the 1930s came to see Cather’s work (as well as that of Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, and other writers depicting small-town America) as reactionary. Granvillle Hicks, in a devastating piece entitled “The Case against Willa Cather,” decries her turning away from “contemporary life as it is,” which he clearly envisions to be “our industrial civilization.” His argument holds only if you are willing to dismiss the rural and small-town people of the Great Plains as unreal or irrelevant, to see their lives as not worthy of a writer’s attention, an attitude long prevalent in American literature which has only recently begun to change.

It is precisely Cather’s allegiance to her subject, her thoroughly realistic picture of the lives of Nebraska homesteaders even as she employs what one critic derisively termed “heroic idealism,” that makes MY ANTONIA so remarkable. Her famous image of a plow, “magnified across the distance by the horizontal light, [standing] out against the sun,” is anything but romantic when taken in the context of Antonia Shimerda’s difficult life. Visiting her after an absence of 20 years, after tragedies and disappointments have come to them both, Jim Burden finds Antonia at the center of a thriving family, enormously proud of the fruit orchards she has brought out of nothing. The reader knows what her victories have cost her, and stands amazed with Burden as he says, “Whatever else was gone, Antonia had not lost the fire of life.”

Cather’s depiction in MY ANTONIA of the situation of rural and small-town women constitutes another form of realism that many of her contemporary critics missed. The vulnerability of young women, especially poor country girls, to sexual betrayal, to scandal and censure in late-19th-century society, informs much of the book. Cather also makes a sophisticated commentary on the distinctions that began to emerge between country people and town people in her youth. Burden’s disappointment with town life, where “the scene of human life was spread out shrunken and pinched,” in comparison to life on the farms surely reflects Cather’s own experience. When she was 12 years old, her family moved from their unsuccessful farm to Red Cloud, where her father set up a loan and mortgage business.

Cather’s nonconformity was much gossiped about in Red Cloud — she frequently dressed in men’s clothing and had the outlandish ambition to become a doctor; she also studied Latin in her attic study. Like Antonia, who had thought nothing of having Jim feel the biceps she’d developed from doing heavy labor on the farm, Cather did not hesitate to work outdoors in “a man’s job” — delivering mail on horseback. On moving into town, she, like Jim Burden, no doubt noted with scorn that a town girl’s soft muscles “seemed to ask but one thing — not to be disturbed.” When Jim describes the “guarded mode of existence” in town as “like living under a tyranny,” he speaks a truth about humanity that we know all too well in the late 20th century. The well-guarded conformity of the many not only stifles the independent spirit, it can destroy it. This aspect of the novel may offer a guide to placing MY ANTONIA in the current debate on diversity in American culture.

“Practicing fiction” proved to be Cather’s means of survival, her way through a world that both rewarded and castigated her intelligence and independent spirit. Critics have often commented on the fact that Jim Burden, in many senses, stands in for Willa Cather: she, too, came to Nebraska from Virginia as a child; she, too, eventually lived and worked in New York City. Cather’s appropriation of a male narrator was considered daring at the time. In recent years some feminist critics have called it reactionary; others have termed it a liberating act in the days before American women even had the right to vote. I see it as a splendid subversion, amplified in MY ANTONIA by Cather’s creation of strong, memorable female characters.

It has less often been noted that Cather also incorporated large elements of herself into Antonia, a character known to be based on Cather’s childhood friend from the Nebraska countryside, Annie Pavelka. Cather was a notorious tomboy, and surely Antonia reflects Cather’s sentiments when she says, “Oh, better I like to work out-of-doors than in a house!” She tells Jim, “I not care that your grandmother say it makes me like a man. I like to be like a man.” But it is worth noting, too, as it says much about Cather’s genius for creating a believable, late-19th-century frontier woman, that Antonia also pursues motherhood with the same innocent vigor. In some ways MY ANTONIA is a perfect illustration of Virginia Woolf’s insight that all writers must be androgynous, willing and able to express both the male and the female. With Jim and Antonia, Cather is “practicing fiction” at the highest level, inventing characters who are like her and not like her, who are and are not their real-life models.

The bold curiosity and independent spirit that did not gain Cather approval in Red Cloud society is of course necessary for an artist, and it is likely that her scorn for the popular art of what she called “adjective and sentimentality” made Willa Cather unpopular with peers and elders alike. The frustrations of Cather’s teenage years in Red Cloud seem to have found release in the columns she wrote for the NEBRASKA STATE JOURNAL from 1893 to 1896, when she was a student at the University of Nebraska. An 1894 piece all but scorches the page: “The Bohemians make large pretensions, it’s a part of their business. But they have great standards, that saves them. … In Philistia there are no standards and no gods. Each house has its own little new improved portable idol and could never be convinced that it was not just as good as any other idol. Here the great standards of art avail nothing.”

In an 1895 essay entitled “The Demands of Art,” Cather makes a revealing statement about the vulnerability of the artist. “When one comes to write,” she says, “all that you have been taught leaves you, all that you have stolen lies discovered. You are then a translator, without a lexicon, without notes. … You have then to give voice to the hearts of men, and you can do it only so far as you have known them, loved them. It is a solemn and terrible thing to write a novel.” Cather was then 17 years away from publishing her first novel; she would spend 10 years in Pittsburgh teaching high school and working as a journalist before moving to New York. There she had more hack work ahead of her at MCCLURE’S before the advice of another woman writer, Sarah Orne Jewett, would take hold in her. “You must find a quiet place,” Jewett wrote Cather in 1908. “You must find your own quiet center of life, and write from that.”

Louise Bogan puts Willa Cather’s achievement in perspective when she writes approvingly that while Cather’s first novel, ALEXANDER’S BRIDGE, opens in Boston, her second, O PIONEERS!, begins with a scene of a high gale in Nebraska. “For Miss Cather, the wind was at last blowing in the right direction,” Bogan concludes. “From then on … she remembered Nebraska.” A large part of that remembering for Cather meant calling forth in herself that love she had spoken of in her youthful manifesto on the demands of writing, but it took her some time to shed her self-consciousness and to develop the artistic mastery that H. L. Mencken found so striking in MY ANTONIA.

Even more than in MY ANTONIA, the land itself is the main character of O PIONEERS!, but in Cather’s second Nebraska novel, THE SONG OF THE LARK, it figures hardly at all; instead, Cather takes a hard look at what it takes for a woman artist to emerge from the constrictions of small-town society. Its heroine, the ambitious and resourceful Thea Kronborg, pursues her career as a singer despite a disapproving family and men who underestimate her. Her triumph is singing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In MY ANTONIA, as Cather returns to rural Nebraska, she contrasts it not only with local small-town society but also with the larger world that the railroad reaches. The heroic vision of the first generation of Nebraska homesteaders that marks O PIONEERS! has been tempered by Cather’s wariness of the “progress” that came barreling along with the advent of the 20th century. A sense of loss permeates the novel, the sense that, as Cather wrote in 1923, in Nebraska, “the splendid story of the pioneers is finished, and … no new story worthy to take its place has yet begun.”

The epigraph from Virgil that Jim Burden employs as a motto for recounting his childhood friendship with Antonia in the Nebraska countryside — “Optima dies … prima fugit” (The best days are the first to flee) — epitomizes the elegiac tone of the novel, and helps to explain the way the book unfolds. Episodic rather than plot-driven, MY ANTONIA is a continual revelation of stories that linger in the memory. In many ways the novel is a perfect evocation of childhood. The task for Jim Burden in recounting the past is not to dwell in it, but to use it to celebrate the present, however reluctantly. The reader comes to understand that both Jim and Antonia have done well not to triumph over circumstance but to keep both memory and hope alive within its bounds.

The task for Cather, as novelist, is to describe the past in such a way that it is truly evoked, with a minimum of nostalgia or sentimentality. This she does in part by making indelible the vigor, the very voice of Antonia Shimerda; we see Antonia running barefoot in her garden, gripping plow handles behind a team of horses, gathering her children to her side. “We all liked Tony’s stories,” Jim Burden tells us, adding that “her voice had a peculiarly engaging quality; it was deep, a little husky, and one always heard the breath vibrating behind it. Everything she said seemed to come right out of her heart.” Perhaps the memory is so vivid to the grown-up Jim because he hears so little anymore that is from the heart. As a successful legal counsel for the railroad, long settled into a disappointing marriage, Jim has learned not to expect so much from those around him.

But his friendship with Antonia remains, and it is one that might strike the modern American reader as something of a miracle. In our mobile society, not many of us can lay claim to such lifelong relationships. I find it significant that Cather’s Nebraska masterpiece has such a friendship at the heart of it, a remarkable friendship between a man and a woman of different cultures and classes, a childhood affection that helps the adult Antonia and Jim reconcile themselves to Nebraska, to the past, and to life itself. “You really are a part of me,” Jim confesses, almost despite himself, at his reunion with Antonia after a lengthy separation. Wisely, he and Cather let Antonia sum it up: “She turned her bright, believing eyes to me and the tears came up in them slowly. How can it be like that, when you know so many people, and when I’ve disappointed you so? Ain’t it wonderful, Jim, how much people can mean to each other? I’m so glad we had each other when we were little.'”