He was born in Okemah, Oklahoma, on July 14, 1912, 12 days after the Democrats nominated his namesake for the presidency of the United States.

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie — “Woody” almost immediately — was Charley Guthrie’s son and like his father ever the optimist. He was Nora’s son too, hers the gift of old songs, and a dreadful fear he would inherit her madness.

Together they raised Woody, his two brothers and two sisters in a middle-class, foredoomed home the neighbors judged one of the finest in that farming community turned oil boom town.

Life in Okemah might have been comfortable, with cotton prices up and beef down, but for the fires.

Fire was to dog Woody, boy and man. A kerosene lamp shattered – the OKEMAH LEDGER reported it as an accident, while folks in town whispered otherwise – and flames consumed his beloved older sister Clara, the one who called him “Woodblock,” when the boy was just months shy of his seventh birthday.

Another blaze leveled the family home, sending the Guthries to live in the weathered London house, high on the weedy hillside overlooking the Fort Smith and Western depot at the foot of Columbia Street.

There were other fires, unexplained. Woody was not yet 15 when his mother hurled a kerosene lamp at a dozing Charley, searing his chest from neck to navel. Members of Charley’s Masonic Lodge arranged to send Nora to the state asylum in Norman.

Years later, and half a continent distant, a short circuit in a newly repaired radio sent flames racing through the child’s bedding, and took the life of Woody’s charming daughter Cathy Ann, “Stackabones,” the youngster who inspired so many of her father’s magical songs for children.

And near the end of his wanderings, Woody splashed gasoline on a Florida campfire; it flared and severely burned his right arm. The puckered scars would leave him unable play guitar. He was left mute, the once restless youth turned rebel now a man resigned to his mother’s fate.

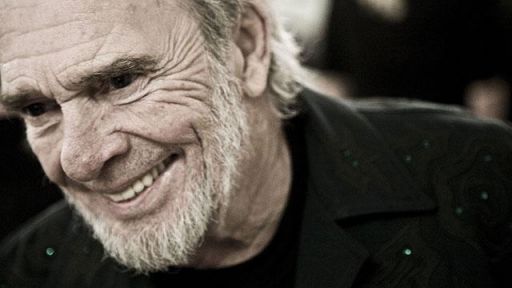

Guthrie was just 42 when he entered the hospital for the last time in 1954. His period of true creativity had spanned no more than eight or nine years, though in that time, he had traveled far, seen wonders and known defeats, and written as many as 1,400 songs. He had traveled Route 66, he boasted, enough to run it up to 6,666, back and forth, across the county as whim and winds took him.

All the while, he never seemed to find what he was looking for.

Marjorie, his second wife, came closest to replacing the mother Woody had lost when Nora was committed to the asylum. But Marjorie put their children first.

Woody sought, needed, so desperately a cause to believe in. Advocating a program of social and economic justice, the Communist Party, USA, offered that and more, but party apparatchiks never asked him to be a member.

Woody reached out to acquaintances – he who knew almost everyone – but could allow close only a bare handful of those he had called upon. There was Huddie Ledbetter, the huge black man pardoned from Louisiana’s dreaded Parchman Farm, and Huddie’s wife, Martha, who opened their Greenwich Village flat to Guthrie. There was Pete Seeger, who would later make Guthrie’s songs so well known; and actor Will Geer, Guthrie’s tutor in Marxist orthodoxy; Jim Longhi, a merchant marine buddy and future lawyer; and Gilbert Houston, stalwart, handsome, the would-be movie star they all called “Cisco.” Those few Woody let in, and damned few others, including the succession of women who sought to mother him and ended up in his bed.

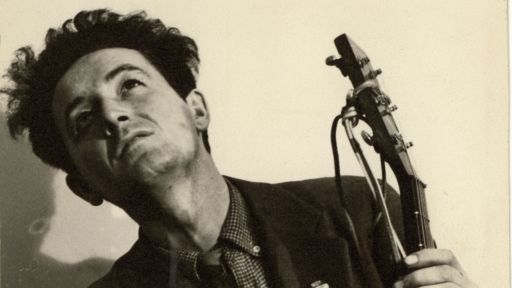

Despite the rich legacy of his songs, still sung four decades after his death from Huntington’s disease, Guthrie was at best an indifferent guitar player, his efforts at Mother Maybelle Carter’s “lick” haphazard.

At the same time, he was a sterling musician. He played harmonica well, if backwards, with the bass notes on the right rather than the left. At other times he played bass fiddle, washboard, spoons, bones, straws, whatever came to hand, rhythmically underpinning other, better players. It bothered him not at all.

He might have been a middling fiddle or mandolin player had he practiced, but he knew he would never be as good as his boyhood friend Matt Jennings. Over the years Matt the butcher would master as many as 600 fiddle tunes. Woody probably never used more than 30 or 40, mostly borrowed melodies, for his 400-plus-recorded songs. Good enough was good enough for Woody Guthrie.

Come spring, an itch came over him, a need to see beyond the next hill, beyond the county line to the next town and the next. He hated riding the rails, fearing railroad bulls and mutilation if he fell beneath a freight car. He preferred instead to travel by thumb, with a handful of paintbrushes shoved in a back pocket. If a song or two didn’t earn a meal in a café or a drink in a bar, he could always paint a few signs or a storefront for 50 cents – enough to last him for a day or two if he didn’t share it with the other hobos camped along a siding just out of town. Mostly he shared it, if he didn’t plain give it away.

He was, like Walt Whitman, whose “swimmy” poetry he disdained, a tangle of unresolved contradictions. And like Whitman, he embraced multitudes.

He was a faithful correspondent, writing, pouring on the page word pictures of startling beauty, letters so compelling that friends kept them for years to read and reread.

He was an unfaithful husband, flitting from lover to lover as easily and as often as he pawned his Sears Roebuck guitar.

He fathered eight children by three wives, and perhaps a ninth, unacknowledged. He left the raising of the first three to his first wife, doted on the next four with Marjorie, and, lost in illness, ignored the last of the children by a third wife. Yet he had such regard for his “manly seed” that he refused to pay for a hotel-room abortion when one of his on-again lovers discovered herself pregnant. His singing companion Cisco Houston secretly gave the frightened girl the $500.

Unconcerned about money, he was generous – to a fault. Guthrie would give away his day’s wages to a migrant family when his own children had to rely on an aunt for dinner. He was just as likely to give his jacket to a shivering fruit picker, his meal to a gaunt mother, or his last pennies to a grimy kid who had never eaten a Tootsie Roll, or drunk a Delaware Punch.

A radio-wise professional by the time he landed in New York City, he played the country boy just off the turnip truck. Well read – particularly in psychology and Eastern religions – he drawled terse comments and aphorisms seemingly sprung from the wind-whipped soil of the Dust Bowl, but more often his own droll wordplay.

Guthrie walked out on a weekly CBS radio show — and its lavish salary — because a sponsor wanted to tell him what to sing on the air. Yet he would meekly accept Communist Party censorship of his unpaid articles for THE DAILY WORKER.

He knew drifters and movie stars, migrant workers and Skid Row barflies, Martha Graham dancers and dance hall floozies, abstract expressionists Jackson Pollack and Robert Motherwell, as well as their wives, girl-friends, and lovers.

And he wrote about them all – in diaries, on random sheets of wrapping paper, on paper bags laid open to catch his torrent of words, his cascade of images, metaphors, allusions, and illusions. He put his name to his autobiography, but shared his royalties with the editor who transformed his bulky manuscript into a rambling narrative. The book was largely fiction – an “autobiographical novel,” Guthrie called it – while his unpublished fiction was real, the stuff of his own life and times.

He was Woody in all his contradictions and complexities – the man you see and hear in Peter Frumkin’s sterling documentary.

— Ed Cray

A professor of journalism at the University of Southern California, Ed Cray is the author of RAMBLIN’ MAN: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF WOODY GUTHRIE.