Gary Toth, Project for Public Spaces

Hannah Twaddell, Renaissance Planning Group

How can transportation support rural livability? This is one of the most vexing questions facing the transportation industry in the 21st Century. But before we can answer that question, we first must answer the fundamental question: what is rural livability? Unlike urban or suburban living, each of which give rise to instant and consistent images within us, rural life is hard to pigeonhole into one set typology.

Is rural life typified by a family farm in Nebraska, Iowa or Mississippi?

Is it living on an unpaved road in an isolated part of northern Vermont?

Is it living in a small village on the mid-coast of Maine, the bayous of Louisiana, the lakes region of Minnesota or the foothills of the Sierras?

Is it living in one of the 19 Native American Pueblos of New Mexico?

Or is shopping, visiting or even living in one of the many great small cities that support rural living, such as Santa Fe, Charlottesville, or Portland, Maine?

The reason defining rural livability is such a challenge is that many of the places mentioned above, plus many more, exemplify rural livability. Rural areas function as systems — not as one hierarchical unit like a tree with an anchoring trunk and connecting branches, but more like a forest of trees with overlapping canopies and intertwined roots. In urban areas, the “forest” is denser and easier to perceive as an integrated entity. The connecting “root systems” that make up rural communities spread out over much more space, making it harder to clearly define their boundaries and relationships. But the connections are no less real, and farms depend on villages, which depend on each other, which depend on small cities, which depend on farms, which depend on tourism, which depend on local business.

Everyone knows what a city or a suburban town looks like, but rural life resists quick stereotyping. Compounding this is that in rural America, it is far more necessary for life to adapt to the local environment and realities: how families deal with water for instance, is very different in the high desert of New Mexico versus the verdant hills of northern Vermont. In cities and in suburbia, the economics of large scale development allow us to overpower nature, bring water into cities, reshape mountains and watercourses, bring all ranges of food into our homes at all seasons. In rural America, the definition of community is much more closely tied to the confines of the landscape, and folks more closely embrace local realities.

So is it any wonder that transportation experts are struggling to decide how we will support rural livability? If you can’t define it, how can we support it? Furthermore, since rural living

encompasses a wide range of formats, our industry’s tried and true “one size fits all” project driven approach of building more roadway capacity just doesn’t fit into rural America — not all of it anyway. And we are just beginning to accept that the “one size fits all” formula applied after World War 2 to America’s “urban/suburban” areas produced unintended consequences and may not be sustainable in the long run. After all, much of what now comprises metropolitan Phoenix, Las Vegas, Denver and other major metro areas was considered rural just 50 years ago.

In the midst of this vacuum, officials representing “rural” states are pushing back on the Obama Administration’s Livability program. They fear that “Livable Transportation” applies only to urban areas which means no more funding for transportation in their districts and states. This fear is understandable, since most of the solutions that have been developed to adjust 21st Century transportation involve de-emphasizing auto travel and fostering walkability and transit. Doesn’t that mean no more roads for Kansas, Iowa, Alabama and South Dakota?

In a word: NO! Or at least it shouldn’t.

But, it also doesn’t automatically mean YES. If by “yes” we are continuing to assume that building more highways is the only transportation response for supporting rural areas. In the 21st Century, rural America is presented with an opportunity that was not available to transportation and community planners of the 1950s, 60s and 70s: a body of knowledge from which to draw lessons learned — both good and bad — about where our 20th century approaches worked and where they didn’t, and the unintended and undesirable consequences can be avoided in the future.

One of the biggest lessons that we learned was this: if transportation and land use are planned separately, the high speed mobility fostered by major roadway expansions will lead to auto oriented community development with remarkably consistent metrics:

-High consumption of open land and rural landscapes

-Cookie cutter development which bears no resemblance to existing towns, farmsteads, geography or natural assets

-Separated land uses, which make transit or walking all but impossible

-Loss of the sense of uniqueness of the existing place

-Loss of the opportunity for everyday socialization that typified rural communities and those that have recently been built for cars (the Project for Public Spaces would describe this as the disappearance of the art of placemaking)

-Congestion, congestion, and more congestion

-High infrastructure costs for new roads, new sewers, schools, new sources of water, etc., caused by the spreading out of development leading to inability to leverage what has already been built

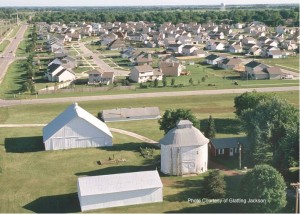

Is that what rural America wants? The photo below shows a scene now all too familiar in rural America, where housing built to satisfy the America dream (for some) destroys the pastoral dream that they were seeking by moving there. It also alters the

dream for the original residents. The institutionalization of suburban style subdivisions has not only altered the landscape forever, it has severed the connections between the roots and canopies that made up the rural community “forests.”

Yet instinctively, when well-intentioned rural officials react to the current transportation debate, it is natural for them to push for more roads. Why not? The strategy of building more roads to support quality of life — whether it works or not — has essentially been the only approach that today’s leaders have ever experienced. We have come to believe that transit is too costly and inefficient to be useful in rural areas, brought on by the belief that there have been marvelous consequences to building new roads. Most of these apparent benefits are direct and easily understood during our daily lives: trips to beaches and resort areas become day trips; purchasing a home in the “country” while still commuting to our job was made feasible; travel to shopping centers for diverse and inexpensive goods became available. We were able to eat tomatoes in the North in winter, get fresh seafood every day in the Midwest, and so on. The problem is that we are only just beginning to get the feeling that the costs of these benefits to rural areas has been too high.

So in places like Central Illinois, the legislature mandated that the state Department of Transportation widen US 50, and did so BEFORE a study of the consequences was made. In South Carolina, a study is continuing of a multi billion-dollar extension of Intestate 73 to the low country. In New Mexico, officials successfully obtained a TIGER grant to widen US 491, although staff will privately admit that the traffic numbers don’t support the need for more lanes. This is inevitable, and as the saying goes: “if the only tool you have is a hammer, then all of the world looks like a nail to you.”

There is another saying, often attributed to Einstein: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” Most of the negative consequences — congestion, skyrocketing costs of infrastructure, environmental damage, etc., are experienced indirectly and build slowly over time. People do not clearly link the negative outcomes that we face today to the transportation choices we made 20, 30 and 40 years ago. We ignore the growing body of evidence revealing that a single minded focus on building more highway capacity ultimately destroys the very rural environments that they were supposed to serve.

The good news is that transportation and community planners — rural and urban alike — now have the tools to help us better understand how different transportation and community investment programs can shape the way they will live in the future. What these tools reveal is that with a thoughtful approach to integrating transportation and land use we can have our cake and eat it too: we can have growth and yet maintain the lifestyle that we like. We can take the best of our 20th Century planning and investment practices and adapt them to help us succeed in the 21st Century.

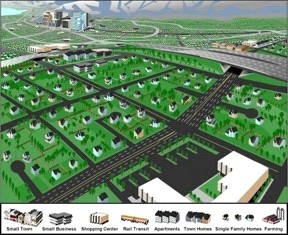

Scenario planning tools, for example, can forecast the consequences of investment in different modes of transportation, investment locations and pricing strategies. When combined with visualization tools, citizens in every region can define in words,

Visualization of how “business as usual” growth would fill the Utah countryside with development || Image: Gary Toth Visualization of how “business as usual” growth would fill the Utah countryside with development || Image: Gary Toth |

pictures and numbers what rural livability means to them. They can them shape their transportation investments and strategies and community and land use plans to create the outcome THEY want. They can come to understand that doing the same thing that many of us did in the past will create the same outcomes, and that the biggest threat to rural landscapes and lifestyle is an uncontrolled business as usual approach to growth.

Scenario planning is in its infancy but when it has been deployed, it has been fabulously successful. The statewide “Envision Utah” process conducted public values research, held over 200 workshops and involved more than 20,000 residents in deciding their own future. Since the completion of the vision several years ago, they have continued to partner with the participating communities to monitor and steer the rural and urban growth into patterns that the residents themselves desire.

Similar scenario planning efforts have been successful in regions such as the central Virginia region around Charlottesville; the mid coast of Maine; Sacramento; and in rural northwest New Jersey. In each process common themes emerged: residents viewed sprawl as a threat to their rural communities and came to realize that a single minded focus on expansion of highways as the primary way to use transportation to support rural areas was a major contributing factor to the threat. The best types of transportation investments blended improvements across a spectrum of modes and were strategically located to encourage a more sustainable, livable pattern of regional growth.

So how can transportation agencies and professionals support rural livability? There is no one answer. But the support starts with the industry helping both professionals and elected officials to understand that precanned or preconceived solutions, whether they are roadway expansions or walkable mixed use development, can be equal threats to rural areas if those solutions are not sensitive to the context. And the only way to properly learn the context is to engage residents of rural areas in planning initiatives that help them clearly define their desired future with a full understanding of what that means. Professionals must help communities facilitate their self-determination instead of dictating outcomes. To accomplish this, a number of fundamental principles need to be followed:

-Both politicians and professionals must ween themselves off of their craving for one big solution to “address the problem once and for all.” In rural areas, transportation solutions will need to be packaged in ways that address the communities unique context and desires for the future. These could range from simple wayfinding to building a bus shelter to rightsizing a Main Street to safety improvements to regional roads to even widening highways.

-Solutions MUST be Context Sensitive! For example, widening or realignment might be appropriate in between villages but not within the village core.

-All system expansion, whether it be highway or transit, must be carefully examined to consider its potential to shape future development patterns –- for better or for worse.

All of the above must be grounded in well designed planning processes that engage residents in the region, commuters, businesses, private developers and public agencies.

Placemaking is the key to creating great communities. Design and planning must support the social connections that are essential to the identity and quality of communities of all shapes and sizes.

Politicians and professionals must understand that transportation is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. The end result which we must strive for is a livable, sustainable community that is supported by its transportation system, not defined by it.

So back to the original question: how can transportation support rural livability? While there is no one answer, the above principles must be used to develop a portfolio of transportation solutions sensitive to the unique contexts of rural communities and mindful of how the secondary and cumulative effects of those “solutions” will affect the long term quality of life of the people throughout the region. Sometimes we will need to shrink roads and slow down traffic; sometimes we will need to widen them and speed up traffic. Sometimes we will need to invest in bus service and sometimes we will need to build new rail. One size will not fit all. A single minded mission to channel most of rural transportation investment into bigger and faster highways to create “accessibility” will be as damaging if not more so than building no new roads at all.

ABOUT

GARY TOTH

An experienced transportation professional, having worked over 36 years in transportation, and environmental planning, and the integration of both into land use and community planning. He has been a leader in Context Sensitive Solutions since the beginning of the program in the 1990s. Now retired after a long career at the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), he is the working Senior Director, Transportation Initiatives with the Project for Public Spaces. As a member of the T4America Coalition, the Sustainable Urban Design Working Group of the American Public Transit Association, the Strategic Highway Research Program’s Technical Coordinating Committee for Capacity, and FHWA’s ITS Advisory Committee, he remains in the middle of transportation reform in America. In 2008, Gary authored the Citizen’s Guide for Better Streets, a stakeholder oriented guidebook intended to share insider transportation tips with citizens. The Citizen’s Guide was used as the basis for a webinar series that he delivered in 2009 in support of the AARP’s Livable Communities program. He is the primary instructor for PPS’s Streets as Places training program, held at PPS in Manhattan, as well on the road. He has also developed a Healthy Living by Design training module for the Center for Disease Control’s Strategic Alliance for Health, as well as a Streets as Places training module for the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Main Street program.

HANNAH TWADDELL

A Principal with the Charlottesville, Virginia office of Renaissance Planning Group. With 21 years of public and private sector planning experience, she specializes in helping communities to envision and plan their desired future by coordinating strategies for economic development, environmental preservation, transportation, and urban design. She has developed regional and corridor-level transportation plans for a wide variety of places, ranging from older industrial cities in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey to growing regions, towns, and rural communities in Texas, Virginia, North Carolina and Florida. At a statewide scale, she recently assisted Virginia with the update of the statewide transportation plan, and designed a web-based toolkit on transportation and land use planning for the Montana DOT.

At the national level, she co-authored a study of best practices in rural land use and transportation planning for the National Academies Transportation Research Board; helped develop a nationally distributed course on land use and transportation planning for the National Highway and Transit Institutes; and assisted AARP with a research project on “complete street” design for older drivers and pedestrians. She speaks regularly at national conferences, provides occasional research and training assistance to the Federal Highway Administration, and serves on the Metropolitan Planning and Policy Committee of the Transportation Research Board.