Tom McNamara, Blueprint America

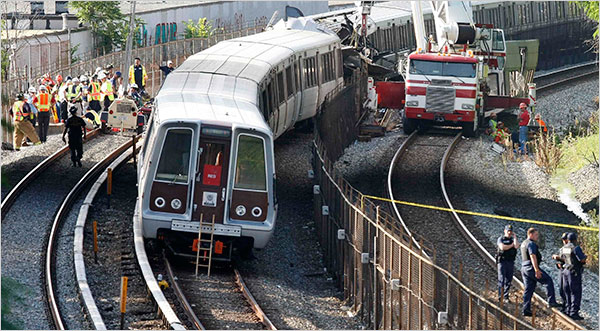

D.C. Metro crash || Photo: Reuters D.C. Metro crash || Photo: Reuters |

Following the subway accident on June 22 in the Washington, D.C. Metro, resulting in the deaths of nine commuters, it was made known that federal safety officials had previously warned that the type of train cars involved could be unsafe in crashes, and called for them to be replaced or, at least, strengthened.

Still, the Washington transit agency did nothing after the federal warning. Not because they did not also see the same problem, but because the agency could not afford to replace the cars, which make up more than a quarter of those used in the system.

Metro — like most mass transit agencies throughout the country — is on the verge of operating in deficit, as a shortfall of $154 million is projected for fiscal year 2010.

A tax shelter, also, according to the terms of a lease-back agreement — in which Metro raised extra funds by selling its trains to private companies, such as SunTrust Banks Inc. and KBC Group NV, that would, in return, lease them back — meant the leased cars, like the ones involved in the accident, have to remain in service until 2014.

According to Bloomberg, “The National Transportation Safety Board had advised Metro to improve its rail cars after a January 1996 collision that killed a train operator. In a 2006 report, the NTSB said it was dropping the matter because (Metro) was citing funding concerns related to lease-back agreements…”

The problem: Any federal mass-transit inspections or findings are nothing but symbolic at-best. Unlike with the Food and Drug Administration, for example, the government cannot recall flawed equipment or issue citations for ignoring recommendations.

Transit State of Good Repair

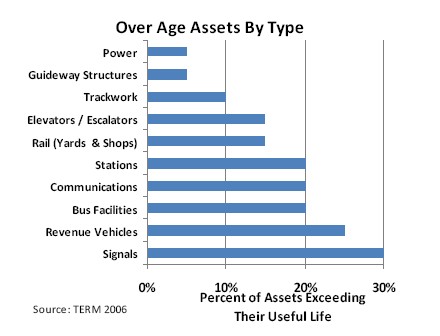

Graphic: Federal Transit Administration Graphic: Federal Transit Administration |

A 2008 report by the Federal Transit Administration, “Transit State of Good Repair,” said, “Roughly one-quarter of the nation’s bus and rail assets are in marginal or poor condition (implying these assets are near or past their useful life or have one or more defective or deteriorated components). The proportion of assets in marginal or poor condition jumps to one-third when the analysis is limited to the nation’s nine largest rail agencies (including these agencies’ non-rail assets).”

The disrepair, according to the report, is the consequence of the fact that “the total level of investment required to bring the nation’s bus and rail assets to a state of good repair is currently estimated at $25 billion ($2004). This investment would effectively replace all assets that currently exceed their expected useful life and address delayed rehabilitation activities. After eliminating the backlog, an additional $9 to $11 billion from all sources is required annually to maintain this state of good repair into the future. At present, annual capital reinvestment rates are only 60 (percent) to 80 (percent) of that required to address both the existing backlog and normal replacement needs.”