Movements to advance American infrastructure, since the beginning, have been brought on by times of national crisis. In an extended interview from Blueprint America: Beyond the Motor City, Eric Rauchway, professor of history at the University of California, Davis, makes the case that it was the Civil War that set the stage for the Transcontinental Railroad; that it was the Great Depression that made possible the public works projects of the New Deal. But, will the current American crisis — the Great Recession — advance infrastructure again?

THE CIVIL WAR MADE IT POSSIBLE TO BUILD THE TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD

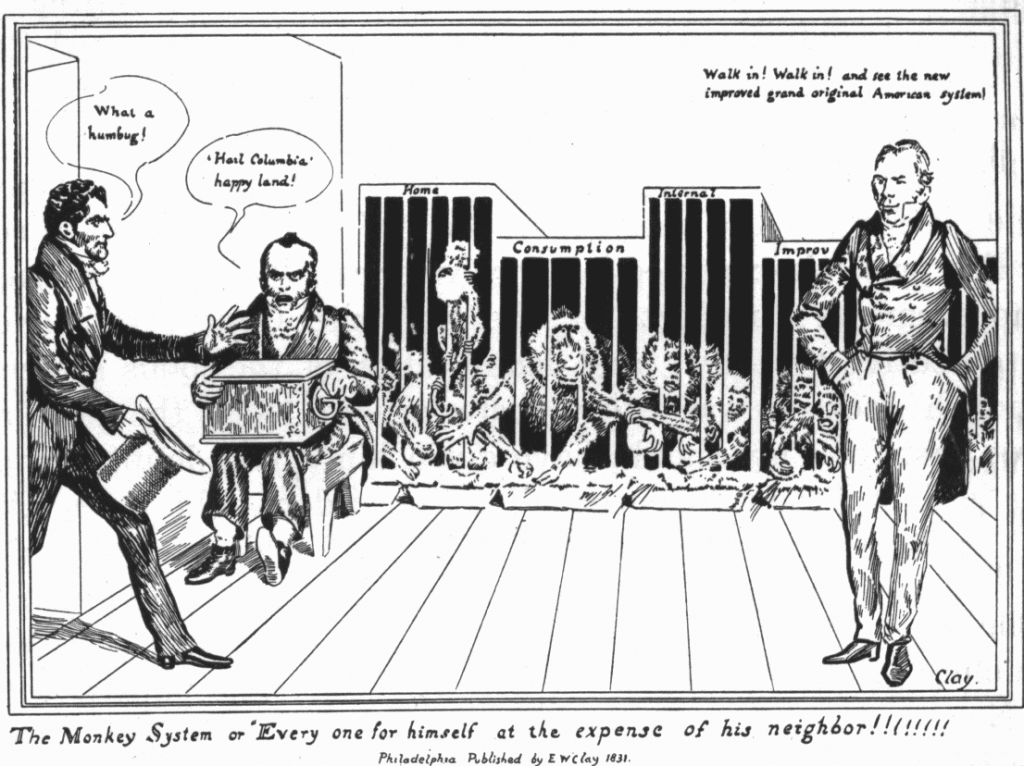

The Monkey System or Every One For Himself || “Walk in and see the new improved grand original American System!” says Henry Clay (far right). The cages are labeled: “Home, Consumption, Internal, Improv”. This 1831 cartoon satirizing Clay’s American System depicts monkeys, labeled as being different parts of a nation’s economy, stealing each other’s resources. The Monkey System or Every One For Himself || “Walk in and see the new improved grand original American System!” says Henry Clay (far right). The cages are labeled: “Home, Consumption, Internal, Improv”. This 1831 cartoon satirizing Clay’s American System depicts monkeys, labeled as being different parts of a nation’s economy, stealing each other’s resources. |

The country’s first national plan to see fruition was put forward in 1829 by Henry Clay, the U.S. Secretary of State, when he called for an “American System.” Using the nationalist sentiment of a United States that followed the War of 1812, Clay proposed a government program to standardize and bring together the nation’s agriculture, commerce, industry and infrastructure. The System: a tariff to protect and promote American industry; a national bank to foster commerce; and federal subsidies for roads, canals, and other internal improvements, eventually including the railroad, to further develop the country.

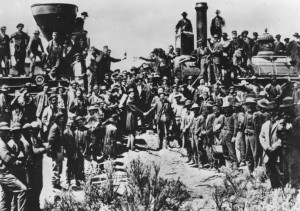

“Golden Spike” – the ceremonial final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, was hammered on May 10, 1869 in Promontory Summit, Utah. “Golden Spike” – the ceremonial final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, was hammered on May 10, 1869 in Promontory Summit, Utah. |

It was this American school of thought that President Abraham Lincoln ultimately took up, implementing in 1862 the Homestead Act, granting 160 free acres to each family that could farm them, and the Pacific Railway Act (the Transcontinental Railroad), connecting rail from coast to coast. As a result, Americans moved west — settling along rail lines where they could work the land. And with settlers came commerce and, soon, industry — new communities were built. But, it was not until the crisis of the War Between the States that such Acts could pass. In 1856, a similar bill to the Pacific Railway Act never made it out of committee as the Senate lacked a consensus. What was different just six years later was a united Congress — with seven States seceding from the Union — led by a president making the argument for uniting the country again — and the Transcontinental Railroad, eventually, would do just that. In less than ten years, the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of America were connected by rail.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION SET THE STAGE FOR THE PUBLIC WORKS PROJECTS OF THE NEW DEAL

In reviewing the programs of the New Deal in 1939, a government report said:

Here was a country with a great and growing need for more schools, more highways, more bridges, more waterworks, more services of all kinds. Here was an army of men willing and able to build them. Here was industry hungry for orders for the needed materials. The idea was to bring all of them together. The job would have to be done some time, why not now?

After the Stock Market crashed in 1929, American unemployment soon rose to 25 percent. That number peaked in 1933, the year in which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office. There are just as many historians and economists that credit FDR’s New Deal policies with ending the Great Depression as there are that say they only made it last longer (A 1939 survey asked Americans to name the best and worst things President Roosevelt had done. The top answer to both questions was the WPA.)

While the country did not return to 1929 GNP levels for over a decade and still had an unemployment rate of about 15 percent in 1940, the New Deal — through the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA)and the Public Works Administration (PWA) — put out of work Americans back to work and, at the same time, modernized a national infrastructure largely still of the last century — bringing running water and electricity to rural areas and putting in place the framework for what would later become the Interstate Highway System.

The WPA, for example, built or improved 651,000 miles of roads, 19,700 miles of water mains and 500 water treatment plants. Workers built 24,000 miles of sidewalks; 12,800 playgrounds; 24,000 miles of storm and sewer lines; 1200 airport buildings; 226 hospitals; more than 5,900 schools, and more than two million privies.

AND, THE GREAT RECESSION WILL…

When Congress passed President Barack Obama’s plan to stimulate the national economy in Feb. 2009, infrastructure projects, above all others, were supposed to be the fastest-acting pieces of the $787-billion package. While much of the law went to cover tax cuts, some $110 billion went to general infrastructure and energy improvements — of which $27 billion went to highway projects and $8.4 billion went to mass transit projects.

But, the effect has been up for debate.

As of July 10 of last year, for example, more than 3,600 of the 5,600 road projects approved by Washington — including six of the 10 largest approved projects — had not been been started. Lawrence H. Summers, the president’s top economic advisor, said the program shouldn’t be judged by short-term results — “the peak impact of the stimulus on jobs is expected not to be achieved until the end of 2010.”

President Obama, with Vice-President Biden, signing the stimulus bill into law last February in Denver. || Photo: The New York Times President Obama, with Vice-President Biden, signing the stimulus bill into law last February in Denver. || Photo: The New York Times |

Still, the White House calculates that every $1 billion spent on highway work will create 11,000 jobs, directly or indirectly. Private estimates are as high as 35,000 jobs per $1 billion.

At the same time, the Government Accountability Office recently found that 9,200 stimulus recipients reported no job creation, despite receiving a total of $965 million. Almost 4,000 other stimulus recipients, who are still waiting to receive funding, reported creating or saving more than 58,000 jobs. The end result: the ineffectiveness of tracking the stimulus — especially in job creation tied to infrastructure spending — will bring into greater question any future attempts of similar investments.

A second stimulus plan — a $154 billion jobs creation package — is in the waiting on the Senate floor. Though passed by the House in December, it was only by a vote of 217-212. The bill, entitled “Jobs for Main Street,” will spend $27 billion on highway projects and $8.4 billion on mass transit projects. Sound familiar?

All of this comes as the economy lost another 85,000 jobs at the end of last year — and the national unemployment rate remains at 10 percent.

Sources: American Public Transportation Association, The Associated Press, Government Accountability Office, The Los Angeles Times, National Archives, ourdocuments.gov, United States House Appropriations and Ways and Means committees, United States Senate, United States Senate Appropriations and Finance committees, The Wall Street Journal