Many people believe the Triborough Bridge in New York was built by the WPA, the Works Progress Administration. But it wasn’t. It was built by the PWA, the Public Works Administration.

The confusion is easy to understand, given the similar abbreviations of the two New Deal programs. But somehow it’s the WPA that gets all the fame. The PWA seems to have disappeared from Americans’ collective memory, even though its structures are all around us, and some of them are enormous.

Aerial view of the construction of the Triborough Bridge, New York. 1939. Courtesy Library of Congress. Aerial view of the construction of the Triborough Bridge, New York. 1939. Courtesy Library of Congress. |

PWA workers built the state capitol building in Oregon, the highway linking the Florida Keys to the mainland United States, the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, the Federal Trade Commission Building in Washington, D.C., the city hall in Kansas City, Outer Drive Bridge in Chicago, the Ellis Island Ferry Building, Washington National Airport and the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state.

They built thousands of miles of roads, hundreds of sewage disposal plants, and thousands of schools. They built or improved hundreds of airports.

These PWA projects were meant to create a useful and sometimes beautiful infrastructure for Americans to use, but the PWA’s main purpose was to help the country climb out of the Great Depression.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed legislation authorizing the PWA on June 6, 1933, during his first 100 days in office.

Roosevelt and his advisers hoped that by building public works, the PWA would stimulate the construction industry and put people back to work. As a government report said in 1939:

Here was a country with a great and growing need for more schools, more highways, more bridges, more waterworks, more services of all kinds. Here was an army of men willing and able to build them. Here was industry hungry for orders for the needed materials. The idea was to bring all of them together. The job would have to be done some time, why not now?

The PWA was not a work-relief program, like the WPA, which was created two years later. People working on PWA projects didn’t have to be on relief, but the program was meant to help reduce the relief rolls.

Roosevelt said repeatedly that getting people to work was better than giving them handouts.

“The dignity of work sounds trite, but if you read newspapers in the 1930s, everyone talked about that,” says Lorraine McConaghy of Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry. “They missed a paycheck, but they [also] missed feeling useful.”

The PWA solicited proposals for projects from around the country, and it received some doozies. “One was a rocket to the moon,” says sociologist Robert Leighninger, author of Long Range Public Investment: The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal.

“There was the Kansas preacher who thought that this PWA was a program where he could apply for bibles for his community. He didn’t want to build anything, just wanted to spread out bibles. There was a mayor who thought maybe his office could be redecorated with PWA money.”

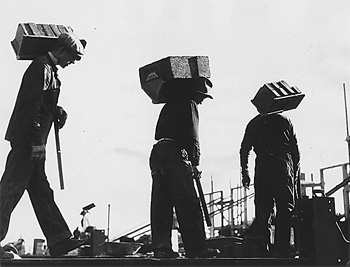

Workers carry bricks to the PWA construction site of Teaneck High School in New Jersey.Courtesy Library of Congress. Workers carry bricks to the PWA construction site of Teaneck High School in New Jersey.Courtesy Library of Congress. |

And one applicant suggested building a moving sidewalk across the country.

But Leighninger says most proposals weren’t silly. “Most of them were solid projects like water works and schools, parks and police offices and city halls,” he says.

Some of the projects would be built by the federal government alone, and others were done in partnership with local governments.

The PWA was criticized for being too slow to get started. Part of the problem was that large public works projects require planning before shovels can go into the dirt. And part of the problem was that the program’s director, Harold Ickes, was so scrupulous about vetting the proposals. Leighninger tells the story of Ickes inserting passages of Alice in Wonderland into a proposal, to see whether his staff would read it thoroughly enough to notice. They didn’t, and he let them have it.

PWA projects did not immediately turn the economy around, so Roosevelt turned to other programs, such as the Civil Works Administration, followed by the Works Progress Administration; these programs could do smaller projects that were quicker to set up.

The PWA issued a report in 1939, titled “America Builds,” arguing that the PWA had in fact stimulated the economy. By then it had built thousands of projects, spending billions of dollars on materials and wages. The report estimates that PWA projects used more than one billion man-hours – 1,714,797,910, to be exact. The report said that wages paid on those projects were plowed back into the economy many times over:

A worker gets a PWA job. He receives his first pay envelope. He needs a suit of clothes, so he spends a part of his pay at the clothier. The clothing dealer takes part of the money and pays the jobber. The jobber takes part of the money and pays his manufacturer. The manufacturer pays his workers and buys more cloth from the mill. The mill owner, in turn, takes part of the money and buys wool and cotton, and perhaps more machinery, and so on.

In fact, the report argued that the PWA’s success provided evidence that governments should undertake public works during economic bad times to stabilize the economy.

Historians and economists differ on how much effect the New Deal building programs actually had on the economy. The building programs “didn’t bring the Depression to an end, but they reduced the magnitude of it and enabled people to survive who would have had an impossible or difficult time surviving without them,” says Richard Kirkendall, emeritus history professor at the University of Washington.

Kirkendall and many other historians also argue that the infrastructure built by agencies like the PWA was essential to the Allied victory in World War II. PWA dams provided electricity to power war plants; its roads and airports enabled troops and goods to move efficiently. The PWA contributed directly to the military, too. It built aircraft carriers, submarines, and military planes.

Many historians argue that the New Deal jobs programs helped preserve capitalism at a volatile time in history.

“It often seemed to me the possibility of some kind of a revolution was there, and these programs were politically significant as well as helpful to individuals and families,” says Kirkendall. “Fascist ideas were circulating in America at the time, as well as socialist. We could have moved in a quite different direction, and I think those programs were helpful in preventing us from moving in a totalitarian direction of some sort.”

After the war, the infrastructure left by the building programs contributed to post-war prosperity, says Jason Scott Smith, history professor at the University of New Mexico and author of New Deal Liberalism.

“This investment in America’s infrastructure is what helps make possible a national marketplace after the end of World War II, connecting regions, building hundreds of airports, building thousands of miles of roads, bridges, sewer systems, you name it,” Smith says.

Smith points out that Americans are still using that infrastructure today, both the huge things, such as bridges and dams, and the smaller things, such as schools and sidewalks, usually with no idea that they were built by the PWA.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Bridge to Somewhere” is an American RadioWorks production as a part of Blueprint America. Produced by Catherine Winter and edited by Mary Beth Kirchner; help from Scott Hunter. The American RadioWorks team includes Kate Moos, Ochen Kaylan, Craig Thorson, Marc Sanchez, Ellen Guettler, Emily Hanford, Suzanne Pekow, and Stephen Smith.