Tom McNamara, Blueprint America

The transportation bill — the massive legislation authorizing and funding the country’s roads and mass-transit infrastructure (from highways to bus lanes to railways to bike lanes) — expires every six years. That, however, does not mean a new bill is passed every six-years. It’s Washington, D.C., after all.

The current transportation bill first expired last September. And not unlike ‘The Bill‘ from the 1970s children’s program Schoolhouse Rock, it has been spending a lot of time sitting around Capitol Hill, waiting to be rewritten. That is why it’s the current transportation bill that expired last September.

“You sure got to climb a lot of steps to get to this Capitol Building here in Washington — But, I wonder who that sad little scrap of paper is…” || Schoolhouse Rock “You sure got to climb a lot of steps to get to this Capitol Building here in Washington — But, I wonder who that sad little scrap of paper is…” || Schoolhouse Rock |

But, to call it the current transportation bill is no longer technically correct. It expired, again, over the weekend and was not extended by Congress (one Senator from Kentucky was able to filibuster the vote) — technically there is no legislation governing the country’s transportation system on the books (at least for now).

Rewriting the bill, after all, is no Schoolhouse Rock song and dance — it’s politics. While there is no law today, more than 2,000 lobbyists have been spending millions in attempts to influence the lawmakers putting together what could be a $500 billion new transportation bill. But perhaps more than the money, the legislation has the potential to lay down the blueprint for a new American infrastructure. Then again, so have all the transportation bills that have come before.

Still, will Congress perpetuate a transportation system that funds roads and highways to the near exclusion of mass-transit? Or, will environmental, housing and other community health decisions play a bigger role in the federal decision-making process? Change is in the air, as they say, and reform is on the table. But the special interest, ‘Bridge to Nowhere’-type earmarks still exist. And while reform is on the table, that is where it sits today.

Poor transportation bill — it’s going to be a long long road.

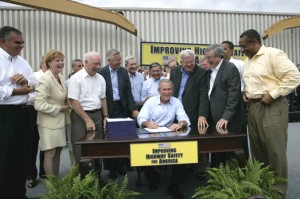

In the meantime, the bill that expired will be extended (shortly, presumably) and continue to be the law of the land. The talks are underway right now. As it has done in the past, Congress will keep extending it, until a new bill (earmarks and all) is negotiated. Nobody knows when that will happen. The last time the transportation bill reauthorization process got under way was September 2003. Then-President George W. Bush signed extensions of the expired law 12 times to keep the country’s transportation programs on track. The new law was finally approved in July 2005.

So far, President Barack Obama has signed off on a one-month extension through last October, a seven-week extension through mid-December and then another through the end of February, as part of a Defense Department spending bill. How does transportation fall under defense? It’s Congress, don’t ask questions.

If the bill is not simply extended for the month of March, which was the plan until Congress stalled last week, here’s how the fourth or potentially fifth extension will work: Before adjourning for the holiday recess in December, House lawmakers passed a $154 billion jobs bill that would allocate nearly $36 billion for highways and transit similar to the recovery package approved earlier that year. The jobs bill, which has also been called a second stimulus plan, includes an extension of the current transportation law through the end of 2010. But as Schoolhouse Rock taught, the measure also had to be approved in the Senate. And that version passed (70-28) just last week with similar transportation provisions in place.

Still, the jobs bill vote signals just how hard it will be to pass comprehensive transportation reform. It was stalled for two-months as a result of the efforts of an emboldened Republican party — no longer facing a Democratic super-majority — calling any further infrastructure stimulus-type investment wasteful as it would only continue to raise the ever-growing national deficit. Amplifying this sentiment, with the one-year anniversary of the signing of the recovery package, has been the Republican line that President Obama can hardly claim credit for improvements in the economy over the past year with three million jobs lost, unemployment at nearly 10 percent and a deficit at $1.6 trillion. At the same time, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently reported that the recovery package had saved or created between 900,000 and 2.3 million jobs. In other words, it’s bad, but it could have been worse.

All along, the Obama Administration has been encouraging Congress to forget all the fancy machinations and create one LONG extension. The President would like to put off any formal debate on transportation reform until sometime in 2011 — after the mid-term elections have come and gone. Why postpone until then? It starts with ‘T’ and sounds like ‘dax increase.’

I.

HOW TO MAKE A BILL; or, welcome to the sausage factory

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien in a web report on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, where at some point a new transportation bill will be debated and voted on.

The term ‘sexy‘ in the past decade in Washington has increasingly been thrown around when couching seemingly unpopular but necessary issues. Popularized in the media and often times echoed by lawmakers, ‘infrastructure’ is a classic example of an unsexy cause on Capitol Hill. That said, maybe no one has ever taken the time to take ‘infrastructure’ out, get a couple drinks into ‘infrastructure,’ turn on some Bob Seger — remember the first time you heard “Night Moves“? — and see where the night ends up. One group that has found the inner beauty of ‘infrastructure,’ however, is the online transportation news source Streetsblog.

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien with Streetsblog Capitol Hill reporter Elana Schor on why transportation legislation matters — especially as Congress will eventually put forward a new bill.

II.

THE MAN WITH THE PLAN

Maybe nobody in Washington is more frustrated with the standstill on transportation than Rep. Jim Oberstar (D., MN). In June of last year, three full months before the transportation law was set to expire, Rep. Oberstar, Chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, introduced The Surface Transportation Authorization Act of 2009 — it was designed to not just authorize a new transportation law but also overhaul all federal transportation programs from funding to practices. To a Washington outsider, and even most insiders, however, what does that mean?

This is where things get so sexy, it’s almost X-rated. (But, in actuality, R-rated. And, in the sense that the Full Monty was R-rated — old man nudity, which, in this case, is very similar to at least the demographic breakdown of the House Transportation Committee.) Now that you have pictured the Committee naked, it is time to come back.

The gas tax. It’s the third rail of transportation politics. Politicians fear raising it. Most would rather lower it. Remember the summer of 2008 when then-presidential candidate in the Democratic primary Hillary Clinton fell in line with Republican calls to suspend the federal gas tax temporarily when prices at the pump were around $4 per gallon? With the federal gas tax at 18.4 cents per gallon, the “holiday” would have saved each driver about $30, while costing the federal government billions in revenues to fund transportation. Turns out, the last time the gas tax was increased nationally was in 1993, by then-President Bill Clinton — a 4.3 cent increase on the gallon. Revenue gained from the gas tax has lost about one-third of its purchasing power since then due to inflation. Worsening returns further is the fact that Americans are driving less — with more mass-transit options and consumers counting pennies at the pump — and using more fuel-efficient cars.

Long story short: it’s the federal gas tax that funds the federal Highway Trust Fund (similar to a checking account that continually is in the red — in other words, most checking accounts) that funds transportation projects. At the same time the transportation law was expiring last summer, the Highway Trust Fund was also verging on bankruptcy (as the two go hand-in-hand). As a result, with each extension of the transportation law, funding for the Highway Trust Fund, which not only funds highways but also transit, has also been solidified. For example, when the jobs bill is finally signed, $20 billion in tax dollars will be transferred to keep the nation’s Highway Trust Fund solvent until the end of 2010 — effectively extending the current transportation law until the end of the year.

Still, the CBO has reported that if current transportation spending levels are continued — which the Obama administration hopes to do for at least the next year or more — the Highway Trust Fund would receive slightly less than $400 billion over the next 10 years, with $50 billion of that dedicated to transit. Yet, the fund would be obligated to pay $610 billion to state Department of Transportations across the country over the same period to keep transportation projects going. Transit spending would total about $90 billion, leaving a 10-year estimated deficit of $170 billion for roads and bridges, and a $40 billion shortfall for transit.

In short, the current federal gas tax is not cutting it — new funding sources need to be identified and put into law or the federal government will be forced to raise the national deficit to fund transportation. Otherwise, it will operate at a loss — needing further federal infusions similar to the jobs bill transfer of tax dollars.

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien with the man with the plan himself, Chairman Jim Oberstar of Minnesota on why his transportation bill is what America needs — especially during the Great Recession.

Still confused? What is an “Under-Secretary of Intermodalism” and should you be afraid of him, her, or… It?

Perhaps, this will help — how does the other side of the aisle feel about the Democratic Chairman’s plan? Given the deep partisan divide in Washington currently, the transportation bill is actually one of the few major pieces of legislation that doesn’t fall in line with politics as usual (calling the President a liar, leveraging one’s party at the expense of having a super-majority, incapacitating ‘hip-hop’ artists on airplanes with ‘condor’ grips, etc., etc.). Following the introduction of the bill last summer, the ranking minority member on the Transportation Committee, Rep. John Mica (R., FL), said this of the nature of the Committee:

“Well, I tell you though, if you’re on the Transportation Committee long enough, even if you’re a fiscal conservative, which I consider myself to be, you quickly see the benefits of transportation investment. Simply, I became a mass transit fan because it’s so much more cost effective than building a highway. Also, it’s good for energy, it’s good for the environment — and that’s why I like it.”

Of the 74 Committee members, 30 are Republican. And the majority of those representatives support the Chairman’s bill. Outside of the Committee, however, Republican support lessens considerably as the cost of the bill is projected at upwards of $500 billion (nearly half as much as the current law) with no identified funding sources outside of the gas tax, which does not currently earn enough revenue to cover the proposed legislation. Outside of deficit spending — and even as the reforms in Rep. Oberstar’s bill promise to trim the bureaucratic waste of the federal Department of Transportation — raising the gas tax is the only immediate way to fund such a large bill. Other options such as taxing drivers based on miles traveled and creating a national infrastructure bank to leverage transportation tax dollars to increase revenues are years away.

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien with the other man with the plan, Rep. John Mica of Florida on the transportation bill roadblock.

While it has almost always been the Republican line to not raise taxes — as the Chairman noted, President Ronald Reagan did raise the gas tax back in the 80s — the divide on the transportation bill this time around has not been Republican-Democrat but rather between a Democratic White House and a Democratic House Transportation Committee. Though that divide has become less contentious, it still comes down to a no new taxes understanding, which Rep. Oberstar has certainly come around to since saying the following to the Obama administration last summer:

“Delay is unacceptable — extension of time, extension of the current law is unacceptable. This is the moment to move.”

The new consensus — not in this economy.

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien with Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D., OR) on the other issues facing the transportation bill once Congress and the Administration come to terms on how to move forward.

III.

THE CONGRESS AND ITS CONSTITUENTS

It all started with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, creating the Highway Trust Fund — dedicating a 3-cent per gallon federal gasoline tax — to support the building of the Interstate Highway System.

The problem with this law, which remains to this day, is that a cents per gallon gas tax does not automatically adjust for inflation. As a result, Congress raised the tax in 1959 from 3 cents to 4 cents per gallon, but did not raise it again until 1983. Like today, the gas-crisis and recession of the 1970s made members of Congress unwilling to raise the tax.

The projected completion date for the interstate system, initially, was 1969. But due to inflation and higher than expected costs of construction, it was not finished until 1991, mainly as a result of the low level of the gas tax.

And, as the system neared completion in the 1980s, the Highway Trust Fund no longer needed to devote the majority of its revenue to interstates alone.

With federal money up for grabs, the practice of earmarking began. Congress first included earmarks in a transportation bill in 1982. Since then, earmarking has grown exponentially: from 10 in 1982; to 152 in 1987 (President Reagan vetoed the bill the first time around as a result of all the earmarking, but eventually was overruled by Congress — yet another Schoolhouse Rock lesson learned); 538 in 1991; 1,850 in 1998; and 6,373 in 2005 (President Bush threatened a veto, but had just youtube’d some Schoolhouse Rock himself and thought otherwise). The 2005 earmarks totaled almost 10 percent of the entire six-year authorization. In the scheme of things, 10 percent may seem insignificant, but, at the same time, why then did almost 1,800 special interest groups spend at least $45 million over the first six months of 2009 lobbying Congress on the transportation bill?

According to the Center for Public Integrity, the roster of special interests paying lobbyists in 2009 to influence either the transportation bill itself or the annual appropriations decisions that are made based on the bill’s framework includes:

* More than 475 U.S. cities and 160 counties in 44 states, the vast majority of which are seeking funds for specific projects that will be chosen by Congress;

* More than 55 local development authorities nationwide;

* At least 65 private real estate development companies;

* At least 95 transit agencies, 25 metro and regional planning organizations, a dozen individual states, and the national lobbying associations for all three groups;

* More than 75 road and auto organizations, from highway builders and car manufacturers to interstate coalitions and trucking interests;

* At least 65 construction and engineering groups, from cement and steel makers to domestic and foreign-owned builders;

* More than 45 rail organizations, 50 shipping companies and ports, and 45 additional transportation-centric outfits, from bicycle coalitions to research groups;

* More than 140 universities seeking funds for local projects or campus research centers.

Blueprint America correspondent Miles O’Brien closes with another interview with the Capitol Hill Streetblogger Elana Schor — in a look at the varying meanings of change when Congress takes up the transportation bill.

IV.

THE END OF THE RIDE

In the end, Rep. Oberstar’s bill might be the only transportation legislation introduced, but any number of transportation bills can be drafted by any member of the House and Senate. To complicate things further, while in the House the transportation bill is simply left up to the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee (policy) and the Ways and Means Committee (funding), in the Senate the bill travels through the Environment and Public Works Committee, Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee, and Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. The President, too, can introduce a bill.

This sounds a whole lot better with our friend ‘The Bill’ putting it to song.

And, of all things to get in exchange for a vote, “Sen. George Voinovich (R., OH),” Elana Schor reported last week, “a longtime supporter of quick action on a new federal transportation bill, helped give Democrats a major victory… when he voted for the Senate’s jobs measure after securing a promise for transportation votes in the upper chamber this year.” Apparently, the Republican Senator from Ohio doesn’t want to see this transportation law have upwards of 12 extensions like the last one.