Essay

Broadway & Hollywood

Breadline in New York during the Great Depression

By the early 1930s, the theater capital and the film capital of America were separated by an entire continent. In the early days of the Great Depression, artists had to make a choice: stay in New York, with its harsh winters and gray, shuffling breadlines, working for a business staggering from layoffs and cutbacks, or move to Hollywood, where it was sunny all year round and smelled of eucalyptus, and money was thrown at you in fistfuls by studio executives. Which would you choose? It is, of course, a trick question. Although the motion picture studios jumped at the chance to add musicals to their rosters after the introduction of sound with THE JAZZ SINGER in 1927, it was several years before they mastered the technology of filming a successful musical. The actual sound reproduction was tinny and false, and camera movement was severely limited.

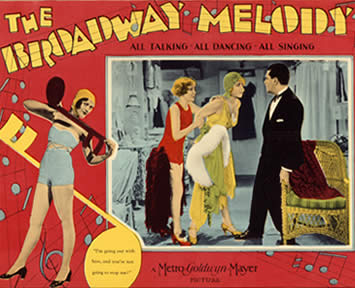

Poster for the 1929 film THE BROADWAY MELODY.

None of this kept the Hollywood studios from exploiting the novelty of sound musicals, and they acquired and filmed an enormous amount of material from 1927 to 1932. Film musicals were either portmanteau revues like KING OF JAZZ, HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, or PARAMOUNT ON PARADE; awkwardly filmed stage adaptations like THE COCOANUTS, SALLY, or SHOW BOAT (1929); or newly crafted stories, often with a backstage theme that glamorized that cosmopolitan city on the East Coast: THE BROADWAY MELODY, BROADWAY BABES, FOOTLIGHTS AND FOOLS. Unfortunately, Hollywood glutted the market with an inferior product and by the early ’30s, audiences were turned off by the technical limitations of the film musical.

It was up to a former marine drill instructor and Broadway dance director named Busby Berkeley to turn all this around. In 1933, he conceived the dances to the quintessential backstage film musical, 42ND STREET, and his visual skill at manipulating both chorus girls and the camera finally made a string of backstage yarns for Warner Bros. competitive with their stage counterparts. Soon, the other studios were churning out their own musical styles (Paramount, elegant and sophisticated; MGM, glossy and overblown; RKO, Astaire and Rogers), and the Hollywood musical was glorying in its heyday, with a barrage of original musicals that would enrapture depression-era America.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers

Every major songwriter from Broadway was under some kind of film contract by the early 1930s. Their responses to the temptations of the West Coast were no more uniform than their personal styles of songwriting. Irving Berlin was initially distrustful of film technology and studio interference, but he was lured back to write TOP HAT for Astaire and Rogers and began a healthy relationship with various studios. (The greatest hit he — anyone — ever wrote, “White Christmas,” came out of the 1942 film HOLIDAY INN.) The Gershwins loved the lifestyle of Hollywood but frequently commuted back and forth to the East Coast, until George’s experience with “Porgy and Bess” sent him back into the arms of RKO. Jerome Kern, never one to suffer fools gladly, surprisingly liked Hollywood and was given the chance to team up with various studio-contracted lyricists like Dorothy Fields, Johnny Mercer, even Ira Gershwin, and produced some of his most extraordinary songs like “The Way You Look Tonight,” “I’m Old-Fashioned,” and “Long Ago and Far Away.” Cole Porter was easily amenable to the assembly-line method of creating songs in Hollywood; he was always content to toss out one song and start over again on another.

But Hollywood never had the one thing Broadway reveled in: creative freedom. In addition to the interference of studio chiefs and tone-deaf line producers, Hollywood has its own form of self-censorship. The Production Code, better known as the Hays Code, was introduced in 1934. Even if film producers wanted sophisticated Broadway material reproduced intact on its sound stages, the Hays Code made that impossible. The most benign lyrics were tweaked with idiotic regularity by inane sensibilities.

Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers in a scene from the film MAKERS OF MELODY.

Rodgers and Hart suffered in Hollywood. For example, they were shunted around from studio to studio, doctoring pictures, writing songs for films that were either cut or rewritten by other hands. Control was always important for Rodgers, so he convinced Hart to escape back to Broadway in 1935. Ironically, the only other Broadway songwriter who had a similar experience in Hollywood was Oscar Hammerstein II, who went about his dreary studio assignments without much enthusiasm. (He did, however, win an Oscar in 1941 for “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” with music by Jerome Kern.)

Hollywood soon relied on its own stable of songwriters, many of whom wrote some of this country’s most immortal songs. Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer had some early Broadway notoriety, but it was on the West Coast that their talents really blossomed; songs like “Blues in the Night,” “One for My Baby,” and “That Old Black Magic” came from some utterly forgettable movies. Sadly, their one great ambition was to write a hit Broadway musical back east in the 1940s and 1950s; it never happened. The most spectacular songwriting team in Hollywood was Harry Warren and Al Dubin, who created the scores for the Busby Berkeley movies with such legendary numbers as “I Only Have Eyes for You” and “Lullaby of Broadway.” Other writers like Dorothy Fields, Frank Loesser, and Jule Styne were nurtured by the studio system and able to extend their successes to Broadway in the late 1940s and 1950s when Hollywood musical production was slowing down.

Cole Porter in Hollywood during the making of the film of his musical KISS ME KATE.

When Hollywood did buy the rights to a Broadway property, it rarely, if ever, made its way to celluloid intact. In general, even the most faithful versions were shorn of several songs for length, but wholesale revisionism was typical of Hollywood, especially with shows from the 1930s. Even small changes in the book musicals of the 1940s and 1950s can change their tone: the 1950 version of ON THE TOWN throws away the World War II setting so crucial to its meaning and KISS ME, KATE in 1953 keeps most of the score, but idiotically has someone pretending to be Cole Porter sort of introducing the movie.

Broadway producers, songwriters, and librettists learned to cry all the way to the bank as film options on their material became more and more frequent in the 1950s, with record sums going for the rights to shows like “My Fair Lady,” which topped out at $5 million. Well into the 20th century, it was Hollywood that would have the last laugh on its East Coast detractors by flooding Broadway in the 1980s and 1990s with stage versions of original Hollywood musicals — a complete inverse of the situation decades earlier — such as GIGI, 42ND STREET, SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN, MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS, and FOOTLOOSE, as well as the Disney animated films like THE LION KING.

Photo credits: Photofest, National Archives and Records Administration,the Library of Congress, Lorenz Hart, Jr., and the Cole Porter Trust