Essay

Broadway & the Rock Score

Gerome Ragni and James Rado.

For the first 50 years of its existence, the music of Broadway was the music of America, but beginning in 1954, a schism grew between Broadway and commercially popular music. That year, Bill Haley and the Comets released a single for Decca called “Rock Around the Clock,” with a heavy backbeat and an electric guitar solo. When it was used to represent disaffected youth in the soundtrack for THE BLACKBOARD JUNGLE, the song became the anthem for an era, selling two million copies by the end of 1955. Rock ‘n’ roll so dominated the times that, by 1957, every entry in BILLBOARD’s Top Ten was a rock song. Rock spoke to youth, it was about youth, and served as the seminal wedge in popular culture to create a divide between parents and children. After the Beatles landed in America in early 1964, the dominance of youth became complete — their singles soon occupied the top five places on the BILLBOARD charts. (They were temporarily unseated by Louis Armstrong’s rendition of “Hello, Dolly!,” which, in a brief paroxysm of revolt from the old folks, reclaimed the number-one spot.) What it came down to, by 1967, was that Broadway was “your parents’ music,” which gave young audiences yet another excuse for ignoring it. The show that brought rock music to Broadway was born downtown at the eastern fringes of Greenwich Village, at the Public Theatre, which was run by the brazen and mercurial Joseph Papp. A couple of unemployed actors, Gerome Ragni and James Rado, cobbled together a musical script about life among the flower children in New York’s East Village. They found a Canadian composer named Galt MacDermot, who had worked in Africa but had never seen a Broadway show. Papp was enthusiastic when MacDermot’s eclectic score of hard rock, Motown, hymns, Indian ragas, and ballads was presented to him. Papp had to pick something provocative with which to open his theater in October of 1967; “Hair” seemed a reasonably unreasonable choice.

“Hair” didn’t have much of a plot; a young man named Claude, set loose among the “tribe” of young hippies in Washington Square, faces being drafted in the Vietnam War. What was far more compelling was the phantasmagoria that exploded around him. “Hair” was, in many ways, simply a revue, showing practically every aspect of the counterculture in a variety of musical styles, dance, and stage effects. In April 1968, “Hair” took the IRT to Broadway, ensconcing itself at the Biltmore Theater on West 47th Street. The show’s nudity was a first for a Broadway musical, as was its full rock score. Both intrigued potential customers, and “The American Tribal Love Rock Musical” — a subtitle coined as a gag — settled in for a run of 1,742 performances.

"Promises, Promises" poster.

The show’s rock score pleased critics of the Broadway sound, and soon some of its more accessible songs — “Aquarius,” “Hair,” and “Let the Sunshine In” — made it onto the pop charts (where they were most emphatically not covered by Perry Como and Rosemary Clooney). Eventually, a younger audience started coming to the show, intrigued by the music they found so compelling on the radio or the cast album. Would “Hair” be the musical savior of Broadway, dragging other scores kicking and screaming into the Age of Aquarius?

At the end of 1968, “Hair” found itself competing with a show that might have had an even more profound effect in renovating the sound of Broadway. When Burt Bacharach and Hal David were approached by David Merrick to score the musical version of Billy Wilder’s movie THE APARTMENT — “Promises, Promises” — they were, next to Lennon and McCartney, the most successful songwriters in pop music. With songs like “Walk on By,” “What the World Needs Now Is Love,” “The Look of Love,” and “This Guy’s in Love With You,” they had, in many ways, defined the American sound of romance in the 1960s; they were also excellent storytellers. Bacharach loved developing songs out of author Neil Simon’s narrative scheme, and he and David were challenged by writing for consistent characters and their emotions. The score itself was biting, tender, and impulsive, and practically shrieked with the sounds of contemporary Manhattan. Bacharach used a completely modern pop sound in the service of a narrative musical comedy.

Marvin Hamlisch with Michael Bennett during rehearsals for "A Chorus Line."

What he didn’t love was the lack of control that was part and parcel of the Broadway musical. “It used to drive me crazy,” he recalled. “There would be eight [substitute orchestra players], including the drummer. The impermanence of Broadway gets to you because everything shifts from night to night. If you’ve got a great take on a record, it’s there, it’s embedded forever.” The recording studios provided more comfort — artistically and financially — and Bacharach moved back to Palm Springs; to this date, he has not written another Broadway score. In his wake, the “contemporary” rock sound could be found instead in such shows as “Dude,” “Via Galactica,” “Sgt. Pepper,” and “Rockaby Hamlet” –all unsuccessful attempts in the early 1970s to put rock music at the service of a Broadway narrative.

More successful were the hybrid scores that used the backbeat of rock music or some of its electronic instrumentation to juice up a more conventional score. Marvin Hamlisch’s score for “A Chorus Line” (1975) used some of these effects, and Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice provided rock-tinged music for their British transfers of “Jesus Christ Superstar” (1971) and “Evita” (1979). In the form of the massively successful “pop operas” of the 1980s (several written by Lloyd Webber), accessible pop/rock rhythms supplanted pure rock and, for a while, the more familiar electric guitar riffs appearing on Broadway entranced a younger generation of theatergoers. But when these megahit scores began tapering off in the 1990s, Broadway producers desperately sought out new ways of capturing the Generation X audience.

Michael Cavanaugh in "Movin' Out."

For the first time, several big-name pop composers contributed scores to Broadway. Elton John made his Broadway debut, working with lyricist Tim Rice on the transfer of his film score for the stage version of “The Lion King” in 1997. When Disney offered John and Rice a chance to write a new version of Verdi’s opera “Aida” for Broadway, John applied his ebullient eclecticism to a score that he wrote at the amazingly fast rate of about one song per day: “It’s truly a pop musical, with spoken dialogue. There are black songs, very urban-based, rhythm and blues, gospel-inspired songs, and kind of ‘Crocodile Rock’ songs, and ballads, of course.”

The same season that John made his debut with “The Lion King,” another major figure in the pop world, from the 1970s, brought his first score to Broadway: Paul Simon. Critics had always invoked Simon’s name as a natural for Broadway, for his sense of narrative was extraordinary and his songs had already provided strong emotional backgrounds for several films. Simon’s Broadway project could not have been less conventional; it was based on the true story of a 16-year-old Puerto Rican gang member, dubbed “The Capeman,” who had stabbed two white kids in 1959. Simon’s look at urban history was both uncompromising and sympathetic, and he provided a breathtakingly wide-ranging score of gospel, doo-wop, Afro-Cuban bop, and Latin salsa tunes. But “The Capeman” lasted only two months, costing $11 million, and when it folded, it took with it one of the most thrilling scores written for a Broadway show in the last 20 years.

Desmond Richardson and Nancy Lemenager from "Movin' Out."

In 2000, choreographer Twyla Tharp wanted to create a large-scale theater piece, and she knew that the swinging narrative songs of Billy Joel held the answer. “He was clearly the best choice because he’s such a good storyteller,” Ms. Tharp said. ”There is rage in his music and guts in his songs. I’ve always known that his music dances.” Tharp created “Movin’ Out,” which tells the story of three Long Island friends and the girls they leave behind during and after the Vietnam War. “Movin’ Out” is performed unconventionally — the show’s large corps of dancers move through the narrative to the live accompaniment of 30 Billy Joel songs performed by a single singer and a back-up band. Although the show hit some shoals on its way in from Chicago, it opened in New York in the fall of 2002 to ecstatic reviews.

But, as became immediately apparent to musicians like Bacharach, John, and Simon, a Broadway collaboration is a very different prospect from a date in the recording studio. Not only do rock and pop composers have to stretch their narrative range to cover songs that work together over the course of an evening, they have to surrender to the grueling politics and unpredictability that go into creating a Broadway show. Broadway babies are born, not made.

Jonathan Larson, however, was a Broadway baby. He grew up in suburban Westchester and was taken by his parents to see “Fiddler on the Roof” and “1776,” yet avidly followed the concerts and recordings of Billy Joel and Elton John. In the late 1980s, he began writing the book, music, and lyrics to a musical update of Puccini’s “La Bohème,” relocated to Alphabet City in the East Village, an area he knew well; it was, indeed, the cutting-edge epicenter of bohemianism. The ambitious score to “Rent,” as the project was now called, required Larson to orchestrate gospel numbers, hymns, tangos, patter songs, and character songs, all to a rock beat.

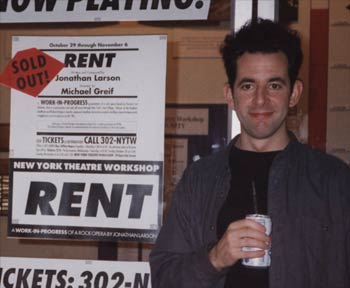

The late composer and lyricist of "Rent," Jonathan Larson.

All signs pointed to “Rent” as the logical successor to the ambitions of “Hair” in the days before it opened downtown at the New York Theatre Workshop Off Broadway. Larson died suddenly after the final dress rehearsal, at the age of 35, due to an untreated aortic aneurysm. His death created the biggest Off-Broadway sensation since “A Chorus Line” opened at the Public Theater more than 20 years earlier. But all the publicity would have meant nothing if audiences and critics hadn’t liked “Rent.” They loved it and, within months, the show transferred to Broadway and won the Tony for Best Musical and Best Score, and ultimately, the Pulitzer Prize.

Since its transfer in 1996, it has run more than 3,500 performances and, even better, attracted a new, younger audience to Broadway, just the way Larson wanted. It’s surprising, absent Larson’s consultation, that the Broadway producers of “Rent” decided to grab a youthful audience by promoting the show as something anarchic, hard-edged, and raw — the very antithesis of “Pippin” (one of Larson’s favorite shows). “Don’t you hate the word ‘Musical’?” read the ad campaign. Larson’s death only complicated the debate about rock scores on Broadway — someone else came along and brought the two together again. Composer Marvin Hamlisch puts the dilemma in the right context:

I have my own thoughts about Broadway and “the Broadway sound” — there’s been a lot of discussion about “Rent” and shows like that with the “rock sound.” … I think rock ‘n’ roll is wonderful and is here to stay, and we’ll have those kinds of shows, but they’re rock shows. Sometimes a good coat that’s been there a long time is better than the brand new one that you have to break in, so I don’t know how far Broadway can take it, how far we can move the envelope.

Photo credits: Photofest, the New York Public Library, Martha Swope, Triton Gallery (© Disney), Joan Marcus, and the Larson family