Essay

Elements of the Musical

Sheet music cover for "Give My Regards to Broadway"

No one person created the musical. It evolved over time and incorporates a variety of influences and elements. First of all, of course, there is the music. Minstrel songs and the cakewalk; Irish ballads and patriotic jingles; ragtime marches and stirring blues; poignant torch songs and jazz ditties; totemic anthems and rock opera — the musical has captured every idiom of American expression. There is definitely a “Broadway” sound, often referred to as “Tin Pan Alley,” a musical structure pioneered by songwriters like Irving Berlin and Richard Rodgers. However, this is by no means the only kind of music to appear on Broadway.

Then, there are the lyrics, the words that go with the music. They can be rhapsodic, witty, risqué, or patriotic. Broadway lyrics have become another form of native poetry — words, catchphrases, sentiments, and stanzas that have entered the American lexicon. The lyrics of Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, and Irving Berlin — to name but three — are routinely quoted in poetry anthologies around the world.

A score by Cole Porter

In the early days of the musical, what mattered most were the songs, and it was essential that they were catchy enough to amuse the audience or provide material for dancers or comedians. But, beginning in the 1930s, the situation, the book or libretto, of the musical started to achieve primary importance. A story or narrative became more frequently the spine of the musical, and in the 1940s, mostly due to the narrative sophistication of the shows of Rodgers and Hammerstein, the songs followed the plot and the characters, rather than the other way around. This narrative spine has made the musical quite influential as a cultural and artistic force; from the epic Kern-Hammerstein “Show Boat” and its view of race relations (1927) to “Oklahoma!” (1943) through “West Side Story” (1957), “Hair” and its antiwar sentiments (1967), “Company” (1970), and “Rent” (1996), the themes of prominent Broadway musicals reflected the controversial, revolutionary, and nostalgic issues of an evolving American culture.

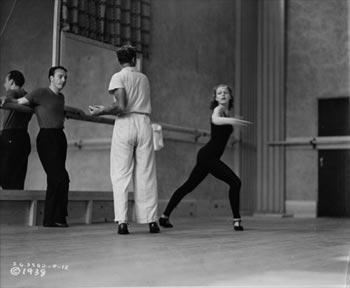

George Balanchine leaning against a ballet bar during rehearsal.

As the musical got more complex, it required a director to shape the production and its design and concept. Strong musical directors like George S. Kaufman and George Abbott emerged in the ’30s; currently major artists like Harold Prince, Jerry Zaks, and Julie Taymor are key to shaping a musical’s success. Choreographers were next to emerge as major artists; in the teens and ’20s, they were simply “dance directors,” but influential choreographers like George Balanchine and Agnes de Mille brought visionary ideas to the stage. With gifted choreographers like Jerome Robbins and Bob Fosse broadening their range in the ’50s, it was only matter of time before they took on the job of director in addition to their dance duties. The director/choreographer became a major visionary force on the stage, guiding every visual and physical moment of a musical. Robbins and Fosse were joined by such talents as Gower Champion, Michael Bennett, and Tommy Tune.

Performers have also been the cornerstone of the musical. They could be comedians like Bert Lahr or Bert Williams; singers like Ethel Merman or Ethel Waters; dancers like Ray Bolger or Marilyn Miller. With the stronger demands of the narrative musical, performers had to become actors as well; indeed, after the success of nonsinging actor Rex Harrison in “My Fair Lady,” actors with minimal singing ability — Richard Burton, Lauren Bacall — became major musical stars. Of course, what Broadway values most these days is the “triple threat” — performers who can sing, dance, and act. In fact, in the past, there were separate dancing and singing choruses; now everyone is expected to do it all. Star performers like Bernadette Peters, Brian Stokes Mitchell, and Nathan Lane appear to have limitless talents.

Marilyn Miller on the cover of a Ziegfeld Theatre program

None of these elements would come together without the producer. The idea for a new musical can come from a writer, composer, or performer, but it can only be realized by a producer. He or she must raise the money for the production; the amount required is called the capitalization. This amount must not only cover getting the show to opening night but also create a financial cushion for several weeks or months until the show catches on with audiences. The producer will rarely spend his own money; he raises it from investors — usually called backers or “angels,” for obvious reasons — and pays himself a salary. If the show is a success and makes back its initial expenditure (recoupment), investors get whatever percentage of their contributed amount back in profits. For example, if you invested $1,000 in “Oklahoma!” in 1943 and it cost $100,000 to produce, you would get 1 percent of the profits after recoupment (distributed weekly). If “Oklahoma!” had flopped, you would have lost all your money; luckily, the show was a big hit: anyone who did invest $1,000 received $2.5 million!

A Broadway musical is both a risky and an exciting proposition. It is the most costly business venture in the theater. Typically, a musical will now cost at least $10 million to produce; to put this in context, 30 years ago, a musical cost one tenth that amount. (Tickets also cost about one eighth as much in 1974.) As hard as it is to raise that money, the rewards can be enormous. Cameron Mackintosh’s four shows (“Cats,” “Les Misérables,” “The Phantom of the Opera,” and “Miss Saigon”) have run on Broadway for more than 62 years total and, internationally, have made more money than these four movies — STAR WARS, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, JURASSIC PARK, and TITANIC — put together. But the rising costs of originating a show have driven away more independent individual producers and opened the field for corporations like the Walt Disney Co. For example, “The Lion King” may well be the most expensive show ever — rumored at above $20 million — and took about four years to turn a profit, but a big company can afford to wait that long for a return on their investment. That’s why there’s no business like show business!

"Miss Saigon" poster

As if these weren’t enough, the story of the musical is also the story of its creators and performers, men and women from every aspect of American — and foreign — society, who came together, often under the most invidious circumstances, to create something that transcended their differences. Refugees came together with native sons and daughters; task masters worked with dissipated alcoholics; white producers championed black performers — and black performers turned right around and made fortunes for those producers; artists fled financial failure for the blandishments of the lucrative worlds of film and television — then fled right back to the stage; gay artists created enduring models of heterosexual romance and heterosexual artists became icons within the gay world; songwriters lost fortunes in the Depression, only to regain them by writing about the Depression itself — the list of ironies and strong compelling biography is endless, each story replete with illuminations about our culture.

Yet, still, the elements that constitute the musical don’t end there. The production of the musical is an art form itself. Complicated and often inflammatory, the craft of producing a Broadway show involves knowing the public’s tastes (and usually challenging it), raising capital, battling societal trends — all on the most expensive real estate in the most fractious city in the world. And, finally, there is the dissemination of the musical, which encompasses a vast narrative of communications and the media. Through sheet music, over the radio, in movies, on television, on gramophones, hi-fis, and CDs, through word-of-mouth, through visiting tourists, servicemen, grandmothers and their grandchildren, the world of the Broadway musical has been brought to every corner of this country and, by extension, the world. The musical is as powerful an image-maker of America as Hollywood has been and the shaping and shifting of that image is another cultural marker.

Photo credits: Photofest; Historic American Sheet Music, “Keep Moving Cake Walk,” Music B-791, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library; Cole Porter Trust; and the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization; and the New York Public Library