Essay

Rise of the Revue

Ziegfeld girl Drucilla Strain

In the years between the world wars, nothing on Broadway catered to Manhattan nightlife like the revue. During the Roaring Twenties, nearly 150 revues opened on Broadway. Pioneered by Florenz Ziegfeld and his elegant “Follies,” revues allowed for an ever-shifting variety of songs, dances, skits, and production numbers. Idiosyncratic comics, specialty dancers, emotive singers, and chorus girls all found a happy home for their particular talents — and costume and scenic designers had a field day, too. Their flash, color, topicality, and brazenness caught the spirit of the age, but revues had their conveniences, too; unlike with later musical comedies, you could easily miss the first act and it wouldn’t make any difference. Revues could be assembled easily, and there was always room for an additional investor, whether it was a newly minted Wall Street broker with a crush on a showgirl or a bootlegging gangster who wanted to see his girlfriend installed at the end of a chorus line.

What revues also provided in spades was opportunity. There were so many chances for a songwriter to get his number placed in a show that the revue became the greatest conservatory for popular music the country has ever seen. Composer Arthur Schwartz and lyricist Howard Dietz gave America some of its most memorable songs during this period: “Dancing in the Dark,” “Alone Together,” “Something to Remember You By.” All were from revues, a form they mastered, and yet they failed to have any successful shows in the musical comedy format. Without the revue as a springboard for their talents, the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, and DeSylva, Brown, and Henderson might have found their road to fame infinitely more arduous or downright impossible.

Here, then, is a scorecard for the more important revues of the period, excepting the “Ziegfeld Follies,” which are in a category of their own:

“George White’s Scandals.” Hoofer White irked his former employer Florenz Ziegfeld no end when he broke away from the “Follies” franchise in 1919 to start his own revue. White’s sharp eye for sleek design and emerging hot talent made his “Scandals” the only real rival to the master’s productions. He had the novel idea of using only one composer for each of his 13 editions, and his particular passion for the latest dance craze allowed his leading dancer, Ann Pennington, to introduce several popular new steps to Broadway, such as the “Black Bottom.” Such future stars as Helen Morgan, Ethel Merman, and Ray Bolger got their first big breaks with White.

“Music Box Revues.” Irving Berlin got into the producing game in 1921 by building the jewel-like Music Box Theater as a showcase for his newest tunes. Before he tired of mounting an annual edition every season until 1924, Berlin placed such timeless songs as “Say It with Music,” “What’ll I Do?,” and “All Alone” in his revues.

The Earl Carroll Theater

“Earl Carroll’s Vanities.” Anyone who wondered where Earl Carroll’s passions lay had only to glimpse one of the innumerable voluptuous tableaux, where dozens of sexy women were draped all over the set wearing as little as possible, that were part of his revues. Carroll tweaked Ziegfeld by placing a sign over his stage door that read “Through These Portals Pass the Most Gorgeous Girls in the World.” His shows prioritized raciness over sophistication, and his comedians included Sophie Tucker, Jack Benny, and Milton Berle. Throughout his nine editions, the most interesting thing Carroll ever did was to get arrested in 1926 when, in one number, a girl was bathing nude in a tub filled with champagne. It wasn’t the nudity that annoyed authorities; Carroll was indicted for perjury when he falsely claimed the tub was filled with ginger ale.

“The Garrick Gaieties.” “The Gaieties” were the “hey-let’s-put-on-a-show” of the revue world. Produced by the Theater Guild in 1925 as a way of raising money, the three editions of the “Gaieties” emphasized youth and wit, and parodied contemporary shows. Famously, the initial edition gave Rodgers and Hart their start with the song “Manhattan,” but other songwriters who got their break here included Vernon Duke and Johnny Mercer.

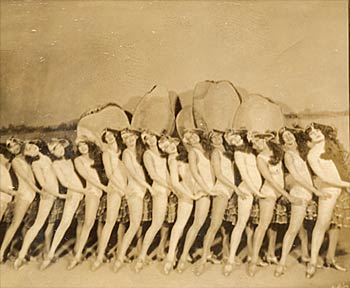

Chorus girls from the revue "Hot Chocolates."

Schwartz and Dietz. Composer Arthur Schwartz was trained as a lawyer, and lyricist Howard Dietz had a day job as MGM’s advertising manager (he created the famous lion), but when they began collaborating at the end of the 1920s, they made beautiful music together. They rode in on the coattails of the “Little Shows,” intimate, sophisticated revues that gave audiences some relief from the bombast of Ziegfeld and White. The team found its true voice in four revues from 1930 to 1935 — “Three’s a Crowd,” “The Band Wagon,” “Flying Colors,” and “At Home Abroad.” Dietz also contributed sketches and direction to many of their shows.

African-American Revues: Lew Leslie was a white producer who brought some of Harlem’s best black talent to Broadway and London’s West End. His “Blackbirds of 1928” introduced the incomparable machine-gun tap technique of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson to audiences, as well as the singer Adelaide Hall. The songwriting team of Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields contributed a break-out score that included “Doin’ the New Low Down” and “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby.” Another black revue of the period was 1930’s “Hot Chocolates,” which transferred from Harlem directly and featured Louis Armstrong in the pit band and onstage performing Fats Waller’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’.”

The revue continued successfully into the Great Depression, but those that survived had a greater discipline or a stronger theme to unite all the various acts. Typical of this change was Irving Berlin and Moss Hart’s “As Thousands Cheer,” which took topical headlines from the daily newspaper as its “unifying principle.” After the advent of the narrative musical, so beautifully rendered by “Oklahoma!” in 1943, it was harder to engage audience interest in a disconnected show. Television put the final nail in the coffin of the revue in 1948 by offering topical material, comedy, and dancing with a speed and economy that the Broadway stage could no longer match.

Photo credits: Photofest, Culver Pictures, the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, and the New York Public Library