In a tribute, the late director Harold Clurman said, “I know of no designer since (Robert Edmond) Jones who more unequivocally deserves the title of master visual artist of the stage than Boris Aronson.” As early as 1926, Kenneth MacGowan referred to Aronson’s work in THE NEW YORK TIMES as “futuristic.” Born in Kiev in 1898, Aronson studied art and stage design with Alexandra Exter, Tairov’s leading designer and an exponent of radical stage design. From this exposure to the Russian experimental school (circa World War I), he began to formulate his theories of stage design: the set should permit varied movement, each scene should contain the mood of the whole play, and through the fusion of color and form, the setting should be beautiful in its own right. He would add, however, that a set is only complete when the actors move through it.

In a tribute, the late director Harold Clurman said, “I know of no designer since (Robert Edmond) Jones who more unequivocally deserves the title of master visual artist of the stage than Boris Aronson.” As early as 1926, Kenneth MacGowan referred to Aronson’s work in THE NEW YORK TIMES as “futuristic.” Born in Kiev in 1898, Aronson studied art and stage design with Alexandra Exter, Tairov’s leading designer and an exponent of radical stage design. From this exposure to the Russian experimental school (circa World War I), he began to formulate his theories of stage design: the set should permit varied movement, each scene should contain the mood of the whole play, and through the fusion of color and form, the setting should be beautiful in its own right. He would add, however, that a set is only complete when the actors move through it.

Boris Aronson

- "Awake and Sing"

- "Cabaret"

- "Company"

- "Fiddler on the Roof"

- "Paradise Lost"

- Michael Bennett

- Joel Grey

- Harold Prince

- Zero Mostel

- Stephen Sondheim

For the Broadway stage, his work was equally inventive. “Walk a Little Faster” featured curtains, one of which was shaped like an iris lens, one that unzipped from top to bottom, and another which covered the performers’ bodies except their dancing feet. “Do Re Mi”‘s curtain of juke boxes evoked a cathedral’s stained glass effect.

Aronson stated that his settings stemmed from either a “documentary,” researched approach or from his imagination. The productions that he did with Harold Clurman during his Group Theater days, “Awake and Sing” and “Paradise Lost,” for example, showed the naturalistic, poor dwellings of the Depression era, while many of his other shows, such as “Archibald MacLeish’s J. B.,” with its starry circus tent, explored the reaches of his and the audience’s imagination.

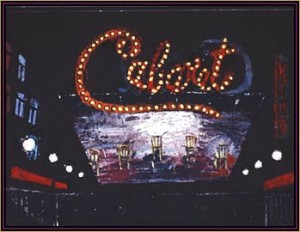

Boris Aronson's set design for the Kit Kat Klub in "Cabaret."

Aronson was a technical innovator who, by employing projected scenery in “Battleship Gertie” (1935) and in Eugene Loring’s ballet “The Great American Goof” (1940), became one of the first exponents of its use. In 1947, the Museum of Modern Art featured his projected scenery for the stage in a show called Painting With Light. He used modern materials to solve design problems, such as in deciding to build a giant mirror for “Cabaret” (in which the audience was to see itself) out of lightweight mylar instead of the usual weighty, and thus dangerous, glass. He even took advantage of new technology to aid the design process, as is illustrated by his use of a color copying machine to work out the pattern designs on the model of “Pacific Overtures.”

His work in ballet and opera, especially Mikhail Baryshnikov’s “Nutcracker” and the Metropolitan Opera’s “Mourning Becomes Electra,” proved that he was a well-rounded designer. Aronson’s design of two synagogue interiors, writing of two books, and successful career as a painter and sculptor who had many one-person shows further distinguished him as one of the few leading figures in 20th-century scene design.

Source: Excerpted from CONTEMPORARY DESIGNERS, 3RD ED., St. James Press, © 1997 St. James Press. Reprinted by permission of The Gale Group.

Photo credits: Photofest, Robert Galbraith, and Lisa Aronson