One of the most cerebral and experimental of theatrical directors and designers, whose fusion of folklore, puppetry, and intellectually demanding themes made her a favorite of those with a taste for the cutting edge, Julie Taymor worked almost exclusively in the world of the not-for-profit theater before bringing her downtown sensibility uptown as director of “The Lion King” (1997), Disney’s remarkable marriage of art and commerce at Broadway’s New Amsterdam Theater. The media giant’s deep pockets enabled her to experiment with new kinds of puppetry, to sculpt, to build, and to test, resulting in what THE NEW YORK TIMES called “the most memorable, moving and original theatrical extravaganza in years.” Disney did not compromise Taymor’s distinctive Indonesian-influenced minimalist style of mixing live actors, puppets, shadows, and masks, and she picked up two Tony Awards (directing and costumes) for her first exposure to mainstream audiences, drawing comparisons to such legends as Bob Fosse, Michael Bennett, and Harold Prince.

One of the most cerebral and experimental of theatrical directors and designers, whose fusion of folklore, puppetry, and intellectually demanding themes made her a favorite of those with a taste for the cutting edge, Julie Taymor worked almost exclusively in the world of the not-for-profit theater before bringing her downtown sensibility uptown as director of “The Lion King” (1997), Disney’s remarkable marriage of art and commerce at Broadway’s New Amsterdam Theater. The media giant’s deep pockets enabled her to experiment with new kinds of puppetry, to sculpt, to build, and to test, resulting in what THE NEW YORK TIMES called “the most memorable, moving and original theatrical extravaganza in years.” Disney did not compromise Taymor’s distinctive Indonesian-influenced minimalist style of mixing live actors, puppets, shadows, and masks, and she picked up two Tony Awards (directing and costumes) for her first exposure to mainstream audiences, drawing comparisons to such legends as Bob Fosse, Michael Bennett, and Harold Prince.

Taymor’s theatrical roots run deep. The Newton, MA native’s backyard performances for family and friends at age seven led to her playing Cinderella (despite preferring the wicked step-sisters), among other roles, with the Boston Children’s Theater. Her first exposure to Asian theater came while visiting Sri Lanka and India on a cultural exchange program at 15. She also studied mime in Paris before beginning her folklore and mythology studies at Oberlin College, where she joined Herbert Blau’s experimental theater company, which included teaching assistant Bill Irwin. After graduation, Taymor went to Indonesia for four years, courtesy of Watson and Ford Foundation fellowships, and developed a mask-dance troupe, Teatr Loh, living with one of the actors in a small compound with a dirt floor and no running water, electricity, or telephone. The tensions she witnessed as a slow-moving, individualistic culture confronted the fast pace of consumer-driven change inspired her first major theater work, “Way of Snow,” performed by an international company of actors, musicians, dancers, and puppeteers.

Taymor became the first woman to win the Tony Award® for Best Director (Musical) for "The Lion King."

Taymor designed her first U.S. production, “The Odyssey” (1979), at the Baltimore Stage, then received her first NYC acclaim as production designer for Elizabeth Swados’ “The Haggadah” (1980), creating a giant seder tablecloth that billowed up, Peking Opera-style, to become the Red Sea, not to mention life-size puppet rabbis debating Passover scholarship and alarmingly graphic plague effects projected through Plexiglas shadow puppets. A mutual friend sent composer Elliot Goldenthal to see the show, calling it “just as grotesque” as his own work, and Taymor and he soon become companions, as well as co-creators of “Liberty’s Taken” (1985), an irreverent look at the American Revolution, produced in Boston and featuring a bobbing-wooden-heads-on-wheels device to satirize the morality-legislating Boston Committee of Safety. There are tentative plans to make movies out of two Goldenthal-Taymor collaborations, their mask-and-puppet adaptation of Thomas Mann’s fantastical novella “Transposed Heads” (1986) and “Juan Darien, A Carnival Mass” (1988), which Lincoln Center revived in 1996, giving Taymor her first Broadway credit.

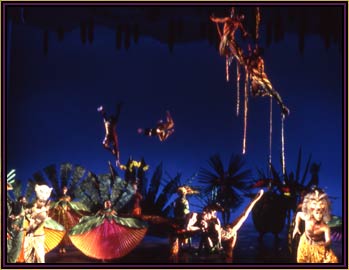

As visually rich as it was musically complex, “Juan Darien” blended rain forest rhythms, the Latin Mass, and Day of the Dead imagery to tell the story of an orphaned jaguar cub, nursed to health and, miraculously, into the human form of a boy, Juan Darien, by a woman who lost her own son to a plague. Combining elaborate costumes and various forms of puppetry — from the Japanese bunraku style of large, eerily lifelike wooden figures manipulated by black-clad puppeteers to simple hand puppets a la Punch and Judy — “Juan Darien” follows the boy’s life up to his flogging and crucifixion and resurrection in jaguar form. All the human characters but one (Juan) wore masks designed by Taymor, haunting oversize heads reminiscent of primitive art and tribal carvings. Her staging resembled a kind of theater-cinema, suggesting the three-dimensional equivalent of pans, tracking shots, and close-ups as full-scale characters and sets shifted to miniatures that turned and moved through stage-space. It was genius, pure and simple, but a little overwhelming for the Lincoln Center membership audience.

Disney, hewing to the artistic high road, gambled that Taymor’s genius could sell tickets, and she, for her part, preserved the essence of “The Lion King” franchise characters while placing her distinctive stamp on them. A soft, furry, bland animal story was anathema to her, so she created puppets and masks with a sharp-edged, rough-hewn look that continued her trademark obscuring of the lines between actor and puppet and costume. Cable-operated masks hang over the actors playing the lions like headdresses, suggesting ancient religious masks, but when the lions turn aggressive, the masks lower smoothly to cover the actors’ faces. One low tech-to-high effect sequence involves the brilliant sea of savanna that as it grows reveals the actors underneath, wearing tables of savannalike hats, but her master stroke was to create life-size animal puppets operated by actors in full view of the audience. A giraffe, for instance, is actually an actor wearing a conelike giraffe neck and head — balanced on arm and leg stilts. It was this idea of the “duality of the puppet and the actor” that sold Disney, and the company did not balk at her changing male monkey Rafiki into a female baboon-cum-shaman, allowing a darker tone to underscore lion cub Simba’s journey to adulthood, and merging South African music with Elton John’s pop tunes.

Julie Taymor

- "The Green Bird"

- "Juan Darien"

- "The Lion King"

- Tim Rice

Source: Excerpted from Baseline. BaselineStudioSystems — A Hollywood Media Corp. Company.

Photo credits: Photofest and Joan Marcus (© Disney)