Today in History: The Legacy of “Strange Fruit” (Op-Ed)

“Far from being dated, ‘Strange Fruit’ in 2021 seems more relevant, and resonant, than ever.”

Ninety-one years ago on August 7th, 1930, two Black men were lynched in Marion, Indiana. The photograph of the scene, in which a huge and seemingly carefree mob celebrates in the shadows of the victims, captures as no other image does America’s most mortifying racial ritual.

(Content warning: link to photograph of the lynching)

Abel and Anne Meeropol | Provided by The Meeropol Family Collection. Reprinted with permission by Michael and Robert Meeropol

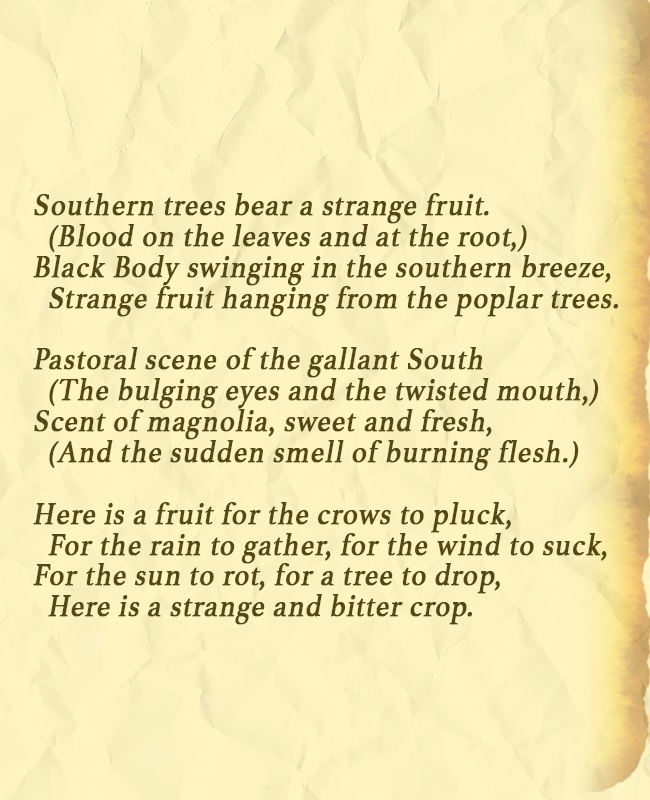

Five years or so later, Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx, created something equally indelible on the same subject in another medium. Initially a poem he called “Bitter Fruit,” it, too, depicted Black men hanging from trees. But his words became immortalized only when he set them to music, and then, in 1939, Billie Holiday began performing the song and shortly thereafter, recorded it. By then, it was called “Strange Fruit,” and it became part of American musical, and racial, history.

I’m no longer so sure that the infamous image from Marion is what inspired Meeropol, as I suggested in my book (Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song) twenty years ago. Meeropol’s poems, and there were hundreds of them, were usually prompted by more recent events, and while lynchings were becoming rarer in the America of his day, they continued to blight the land. Another lynching, in Fort Lauderdale in July 1935 — covered on the front page of The New York Age, a Black weekly he quite possibly read — could well have been the impetus. Then there was the matter of geography. The trees with “blood on the leaves and blood at the root” that Meeropol described were Southern, which Indiana, though a hotbed of the Ku Klux Klan, was not. Meeropol further underlined the locale, savagely and sarcastically, in the song’s second stanza: “Pastoral scene of the gallant South,” it began. Then he quickly raised it yet again, juxtaposing the smell of burning flesh with the “scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh.”

Billie Holiday | Source: Library of Congress

Abel Meeropol’s poem, “Bitter Fruit”

So did the advertisements touting Holiday’s performances of the song at Café Society, the Greenwich Village nightclub, catering to left-wing intellectuals and activists, where she had introduced it. “Have you heard ‘Strange fruit growing on Southern trees’ sung by Billie Holiday at Café Society?” notices in the New Yorker asked. How often, before or since, has the performance of a single song, in and of itself, been considered an event?

Then again, there never had been a song confronting racial bigotry and violence as directly as “Strange Fruit.” Encountering it, especially for those not knowing what was coming, was a jolt. And its presentation by the young – twenty-three years-old at the time — and defiant Holiday only made it more so. All service in the club was suspended as she went into it. The place went dark, with only a single light on her. It closed all her sets – what could one sing for an encore? – and when the lights went up, she’d be gone. “People had to remember ‘Strange Fruit, get their insides burned with it,” said the man who’d made it happen, Café Society’s proprietor, Barney Josephson. (Among other things, “Strange Fruit” illustrates the historic collaboration between two marginalized groups: the song Holiday immortalized was written, staged, and recorded by Jewish men.)

Even in the integrated quarters of Café Society – a rarity even in 1930s New York — some found the song offensive, a damper on a fun night out. In Harlem, too, it was considered a downer. Holiday’s regular label, Columbia, wouldn’t record it, and once someone did – Milt Gabler, owner of Commodore Records (and Billy Crystal’s uncle) — few radio stations dared play it. The conservative Black press largely ignored it or focused on its flipside – Holiday’s far more palatable “Fine and Mellow.”

Even in the integrated quarters of Café Society – a rarity even in 1930s New York — some found the song offensive, a damper on a fun night out. In Harlem, too, it was considered a downer. Holiday’s regular label, Columbia, wouldn’t record it, and once someone did – Milt Gabler, owner of Commodore Records (and Billy Crystal’s uncle) — few radio stations dared play it. The conservative Black press largely ignored it or focused on its flipside – Holiday’s far more palatable “Fine and Mellow.”

And while “Strange Fruit” remained one of Holiday’s signature numbers for last twenty years of her short life — her performances, and subsequent recordings of it coming to embody her increasingly embattled, fragile state — she took care to perform it only in the most congenial of settings.

So initially at least, “Strange Fruit” was a kind of cult song. But two more remarkable things about it have been its durability and ever-broadening reach. After many years in which most other artists steered clear of the song, either out of respect for Holiday (who could ever have put it across as she did?) or fear of the material, many others, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson among them, eventually did. As the civil rights movement of the 1960s and its successors took shape, additional generations of activists came to know it, and be inspired by it. In 1999 Time deemed it “the song of the century.“ Three years later, it was added to the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress.

As lynchings have receded but racial prejudice endures, the song has taken on greater metaphorical significance as an attack on intolerance generally. Earlier this year, following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, it was invoked by Michael Meeropol, Abel’s elder son: only when policemen were convicted of murdering Blacks would “Strange Fruit” become “a relic of a barbaric past,” he said. “But until then, it’s a mirror on a barbaric present.”

Protesters gathering in response to George Floyd’s death.

Then, this past February, came the film “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” which depicted a campaign by Federal agents to bring Holiday down for performing so seditious and incendiary a song. The claim is highly dubious, Lewis Porter has argued recently in Jazz Times. But such mythologizing – building an entire movie around a single song — is itself a tribute to it, as well as compelling evidence of its unique and enduring power. Far from being dated, “Strange Fruit” in 2021 seems more relevant, and resonant, than ever.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.