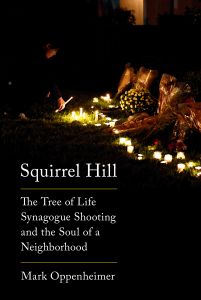

“The Soul of a Neighborhood”: Three Years After the Shooting, Mark Oppenheimer Finds a Hopeful Story in Squirrel Hill (Op-Ed)

When I decided to write a book about the October 27, 2018, attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh — an attack that killed 11 Jews, making it the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history — I was faced with a key decision: do I want to write the story before the attack, or the story after the attack?

The story before the attack, which, I was to learn, was what most people expected me to write, would be about the perpetrator and the victims. About the perpetrator — the alleged perpetrator, I should say, since he has not yet gone to trial — readers would want to know his background, his history, his motivations. What kind of person would shoot up a synagogue? Where did he learn his antisemitic ideology, if that’s what drove him to do the deed? What might have set him on a different course?

“I chose to write a different sort of book, one that focused on the aftermath of the attack, especially all the people who rushed in, trying to help.”

About the victims, readers would want to know (as I would want to know) who they were, what sort of lives they led. They ranged in age from their 50s to their 90s, and none of them was famous; they were good, solid unremarkable folk, the type that Jews call amcha, “Your People,” meaning God’s salt of the earth. Two of the victims were intellectually disabled brothers; two were a married couple. To their families, each of them was unique and precious, irreplaceable. Maybe the role of a book like mine was to portray them in all their uniqueness.

I chose to write a different sort of book, one that focused on the aftermath of the attack, especially all the people who rushed in, trying to help. This was a huge, diverse group that included reiki healers, challah bakers, therapy-dog owners, rabbis from all over the country, and thousands of people who cut checks, sending millions of dollars, from all over the world. I wrote about an Iranian immigrant to the US whose GoFundMe campaign raised over $1 million for the victims; about a rabbi from Whitefish, Montana, who came to town to help out; about a retired carpenter from Aurora, Illinois, who drove through the night to plant hand-made wooden Stars of David in front of the synagogue, one for each victim.

In the end, then, I wrote a hopeful sort of book, one that described the extraordinary outpouring of goodwill that can follow even the most horrific event. I got to describe the dawn, how “joy comes in the morning,” to quote the Psalm. There was a lot of morning joy in Squirrel Hill, the neighborhood where Tree of Life sits; there is no neighborhood in the country with an older, more stable Jewish presence, and its tight-knit, communal spirit was on full display. The shooter was not going to keep these Jews down, and his one act of terror was not going to define them.

“An attack like the one on Tree of Life has consequences for all of us, spreading out in concentric circles.”

Still, there was a cost; all writers’ choices come with costs. Describe one thing, omit another. Sometimes I asked myself how I’d managed to say so little about Jerry Rabinowitz, one of the 11 victims, who in the 1980s and ’90s had been one of the handful of doctors that Pittsburgh’s HIV-positive community trusted to treat them with compassion? I spend hours talking with his wonderfully forthcoming widow, Miri, and what I learned about him could have filled a book of its own. Then there were the victims about whom I never learned much at all. Who was Irv Younger? What about Richard Gottfried — who was he, besides being a well-loved dentist? I talked to Joyce Fienberg’s son, but not for long enough that I ever got a clear picture of who she was. Or maybe I did not ask the right questions.

It’s not just likely that there will be more mass killings, it’s inevitable, given the hundreds we have experienced since the Columbine attack, in 1999. As a country, we have always lived with hate, and now it seems that we live with hate-based mass gun violence. The next attack on a Jewish house of worship came in Poway, California, just six months after Tree of Life. To survive, and thrive, in the aftermath of such attacks, we will need all kinds of stories to light our way. We need to remember those we have lost, but we need, just as urgently, to take stock of the present and future. An attack like the one on Tree of Life has consequences for all of us, spreading out in concentric circles.

In Squirrel Hill, many people have lost friends, or relatives. At the congregations that lost members — three congregations occupied space in the Tree of Life building, and suffered casualties — worshippers have to figure out who will step up to do the work that the dead used to do. In Pennsylvania, some feel a renewed urgency for stricter gun laws. In synagogues around the country, there is heightened security — still. As anyone who has lived in the United States in the years since 9/11 knows, when mass violence comes, it never really leaves. We could spend our time mourning the dead, telling their stories, and we will, when we have time. But will we have time, when there is so much work to be done?

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.